Back to Findings and Recommendations

Irish banks had been national businesses for decades, set up to serve local and national enterprises. However, by the mid to late 1990s, the bigger banks were establishing an international presence; AIB bought into Bank Zachodni in Poland and Bank of Ireland bought Bristol and West in the UK. As Ireland’s economy began to grow, National Australia Bank entered into the retail market. The International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) opened in Dublin which also provided a location for the emerging global non-retail financial business.

Klaus Regling & Max Watson said in ‘A1 Preliminary Report on The Sources of Ireland’s Banking Crisis’:

“From the late 1990s onwards, the world economy was characterised by relatively high growth, low headline inflation, strong liquidity creation, and low interest rates. The literature has named this period ‘The Great Moderation,‘ which can be explained by the positive effects of globalisation, technological progress and productivity increases, and the stronger credibility of most central banks around the world, which had become independent from political interference, facilitating a stabilisation of inflation expectations.”1

Ireland’s profile in world banking and world financial services expanded rapidly and, by the early 2000s, was well established.

Throughout the early 2000s, trade between the US and China grew, resulting in a surplus in favour of China. The Chinese Government recycled much of the new and surplus money back into the US by investing in US treasuries (Government bonds). In turn, the US Federal Reserve (Central Bank) invested the bond monies in US banks and insurance companies for a higher return. A high-risk loop of mutual inter-dependencies stretching from Chinese investors to US householders had formed, with every party in the loop hoping to profit.

David Duffy, Chief Executive Officer, AIB, said:

“… It’s a once in a generation circumstance where the availability of a huge amount of liquidity including retail bank liquidity which wasn’t available before in the sense that it was made available as well as geopolitical events where China, in order to grow, was very much a supporter of a cheap cost of capital through its purchasing of US debt despite the overall levels of debt. …the US consumer became very heavily indebted and that was a contributor to the property boom.”2

The creation of the Euro and the growth of the Chinese economy both affected the world economy. Professor Philip Lane, Professor of International Macroeconomics and Director of the Institute of International Integration Studies in Trinity College Dublin, explained some of the international background:

“China was growing so quickly that it was important in the late 1990s, but by the mid-2000s it was very important. That had trading effects, although maybe less so here. For example, the economies of Portugal, Greece, Italy and so on were quite affected by the rise of cheap imports from China. Financially, the surpluses coming out of China were essentially flowing into the US financial system. Low interest rates in the US prompted, for example, the rise of securitisation in US financial markets and European banks were active in the US system. Therefore, there was a deep connection between what was going on in the US in the mid-2000s and what was going on in Europe. A lot of that was being intermediated through banks. European banks were important in linking the US financial system to the European financial system.”3

David Duffy also said in his evidence to the Joint Committee:

“That cheap money was allowing every market to chase property and when it collapsed in the sub-prime and then was further influenced by allowing banks to go bankrupt in the US, there were many more banks were very close to going bankrupt. So the extraordinary measures of the US Government at the time, both negative and positive, if you put all of those together, it is an exceptional period of time. Ireland’s problem was that we were very badly positioned to react to that given our concentration.”4

From around 2003, the Irish started to invest a very high proportion of national income and personal income in property.5 This was enabled by the ready availability of cheap money on the wholesale money markets.

Brendan McDonagh, CEO of NAMA said:

“I think, when you look at the … again, at the growth in the balance sheets of the banks between 2003 and 2008 … the banks were lending, but they were effectively lending to a longer-term asset class, which was property, but they were funded by short-term cheap, wholesale money market deposits. So, they were borrowing at, you know, one month, three month, six months at around 2% … a lot of it, you know, German money coming into Ireland, looking for a home. And, you know, once the crisis happened, all those depositors withdrew, took their money back and the banks were left long on assets but short on cash.”6

A number of factors within the single currency context contributed to the liquidity crunch preceding the economic crash of 2008, principally:

1. EU monetary union and control of monetary policy

The free movement of capital and its attendant benefits provided a critical rationale for the introduction of the euro. The EU’s developed and expanding status bolstered available liquidity. European investors began to look favourably on Ireland, given its impressive economic performance throughout much of the 1990s and into the mid-2000s.7 A major expansion in liquidity in Ireland was the result.

“…Prior to monetary union, Ireland and Spain had probably under-invested in housing as we had a higher cost of capital than in countries like Germany or France. Given the demographic profile, we needed to invest in housing. In permitting a more rapid adjustment to the housing stock, the lower cost of capital was beneficial. However, it was the failure to appropriately control this surge in investment which eventually proved fatal…”8

2. Design faults of the Euro

The Eurozone was an economic and monetary union that lacked a banking union. The Stability and Growth Pact continued only certain aspects of the convergence criteria, considering that others would be successfully addressed by the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) and European Central Bank (ECB). In the absence of the exchange rate and the domestic interest rate, the behaviour of the Irish economy was allowed to change in ways that would not have been previously possible due to external pressures placed on the punt as the real effective exchange rate deteriorated.

Professor John FitzGerald, Research Professor at the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), told us:

“You do not have the interest rate tool to manage an economy or to manage inflation and, in particular, asset market bubbles. You have to use other instruments, that is, fiscal policy. It was something which we did not anticipate or talk about. It is clear from the literature before monetary union, people were barking up the wrong tree about the problems of monetary union, not just in Ireland but elsewhere that one needs to use fiscal policy to manage housing market bubbles.”9

In the absence of a banking union, where free capital flows were facilitated by the new currency system, Ireland needed to modify its approach to policy formation in the fiscal and monetary spaces. The gaps between the convergence criteria and entry into the Eurozone on 1 January 1999 were sizeable refer to following table. The reference criteria were:

The criteria of an optimal currency area highlights the importance of consolidated fiscal policy across members of the currency zone and the importance of fiscal transfers, as well as labour mobility. These facts were present but considered of the utmost importance in the Irish context. The Irish approach to fiscal policy was coloured by the experience of the 1980s and the fiscal consolidation that took place as part of the protracted recession, and Ireland’s labour market was nearing full employment at the time. According to John FitzGerald:

“…there was a need to use fiscal policy in a different way. In terms of the economics literature, the use of fiscal policy to manage the cycle had gone out of fashion, as the Senator is probably aware, saying fine tuning is not possible. This is not fine tuning, this is stopping disaster by using fiscal policy differently. Hopefully we have learned our lesson.”10

| Inflation (%) | Long-term interest rates (%) | Deficit ratio (%) | Debt/GDP (%) | ERM two-year membership | |

|

Austria |

1.1 |

5.6 |

2.5 |

66.1 |

yes |

|

Belgium |

1.4 |

5.7 |

2.1 |

122.2 |

yes |

|

Denmark |

1.9 |

6.2 |

-0.7 |

65.1 |

yes |

|

Finland |

1.3 |

5.9 |

0.9 |

55.8 |

no |

|

France |

1.2 |

5.5 |

3.0 |

58.0 |

yes |

|

Germany |

1.4 |

5.6 |

2.7 |

61.3 |

yes |

|

Greece |

5.2 |

9.8 |

4.0 |

108.7 |

no |

|

Ireland |

1.2 |

6.2 |

-0.9 |

66.3 |

yes |

|

Italy |

1.8 |

6.7 |

2.7 |

121.6 |

no |

|

Luxembourg |

1.4 |

5.6 |

-1.7 |

6.7 |

yes |

|

Netherlands |

1.8 |

5.5 |

1.4 |

72.1 |

yes |

|

Portugal |

1.8 |

6.2 |

2.5 |

62.0 |

yes |

|

Spain |

1.8 |

6.3 |

2.6 |

68.8 |

yes |

|

Sweden |

1.9 |

6.5 |

0.8 |

76.6 |

no |

|

United Kingdom |

1.8 |

7.0 |

1.9 |

53.4 |

no |

|

1998 reference values |

2.7 |

7.8 |

3.0 |

60.0 |

|

|

Greece (2000) |

2.0 |

6.4 |

1.6 |

104.4 |

yes |

|

2000 reference values |

2.4 |

7.2 |

3.0 |

60.0 |

|

|

Source: European Commission Convergence Reports, 1998 and 2000 |

|||||

Source: Centre for Economic Policy Research.11

3. Foreign exchange risk eliminated

The introduction of the Euro eliminated foreign exchange currency risk across the majority of EU Member States. That provided a platform for access to cheap liquidity by financial institutions from large client deposit bases in different countries. It also helped foster a perception outside the EU that the risks of euro Member States were pegged to that of the best performers, notably Germany with its AAA status. Thus, for certain types of investors, a 10 year Irish bond paying annual interest of 2% was more attractive than a 10 year German bond paying annual interest of 1%. In such a scenario, the short-term gain and risk would trump the longer-term gain and risk, even though the scale, structure, markets and risks of the Irish and German economies were vastly different.

As was stated in the Nyberg Report:

“…The Irish economy and Irish financial institutions were, furthermore, exposed to the expansionary financial incentives associated with membership of the Euro area. The disappearance of exchange risk and the absence of euro-wide inflationary pressures caused a significant reduction in interest rates, compared to the Irish Punt historic rates, while there was virtually unfettered access to funding from European and other capital markets (Figure 1.2). At the same time competition increased via new non-Irish entrants into domestic financial markets…”12

The EU financial institutions used the new Euro denominated liquidity to invest in bond offerings from the Irish financial institutions for an incremental return. The Irish institutions lent to developers who in turn invested in property and construction, seeking to obtain an even higher return. Some investors formed syndicates (group of borrowers pooling monies together) to invest in tax designated and non-tax designated property-related ventures. Householders, along with investors, also borrowed monies to purchase housing and second properties.

Brendan McDonagh said:

“…While some of the lending was to professional, well-managed entities, much of it was to individuals or syndicates whose primary business was not property developments, or who became involved in property developments relatively late in the cycle”13 and went on to say “They were new arrivals, a lot of the professional class. A lot of the professional class got into syndicates, particularly to buy land, and particularly to buy land mainly in … a lot of it in regional Ireland…”14

4. Interest rate harmonisation

Under European Monetary Union (EMU), the ECB sets interest rates to meet the needs of the Eurozone economy as a whole. This resulted in an interest rate which, for many years in the run-up to the crisis, was set at a level which was too low for Ireland. That resulted in a low or, at times, negative real interest rate for Ireland, further aggravating the boom. For countries experiencing low growth or recession, the opposite effect occurred.15

David Doyle, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, said:

“…Prior to the establishment of the ECB the Irish Central Bank was fully responsible for monetary policy and financial stability and regulation. It set interest rates at a level that were appropriate to the specific conditions of the Irish Economy. It lost this authority following the entry into the Euro. The ECB did not appear to regard the question of curbing asset prices or excessive credit growth through the interest rate mechanism as appropriate, viewing this as a matter for the domestic central banks and regulators…”16

Bertie Ahern, former Taoiseach, said:

“…We were … able gradually to remove incentives from the property market but membership of the euro meant that we were unable to raise interest rates. Accordingly… according to the IMF report in the summer of 2009, the housing boom was caused mainly by cheap credit due to low interest rates, along with rising incomes and a strong demand for housing…”17

An IMF Staff Report contained the following:

“The boom years stored up immense problems. Following a decade of export- and FDI (foreign direct investment) led growth supported by broad-based productivity gains, from about 2003 on the Irish economy embarked on a domestic boom underpinned by lax lending. Stiff competition for market share from foreign-owned as well as domestic banks pushed underwriting standards lower, and the feedback effect of rising collateral values fuelled the leveraging process. Rapidly rising property prices also drove high fixed investment in commercial and residential property, and a positive wealth effect fed private consumption, raising incomes and employment. Wages and prices rose, eroding competitiveness and compressing real interest rates. The integration of the Irish financial system into the broader euro area financial landscape, as well as the apparently strong fiscal position of the sovereign, gave Irish banks unfettered access to wholesale funding that turbocharged their asset expansion.”18

During the Context Phase of the public hearings, the Joint Committee heard evidence from Peter Nyberg, Rob Wright, Patrick Honohan and Klaus Regling, all of whom had completed reviews of the crisis. The key findings of these reports as they related to the banks were as follows:

The Joint Committee wanted to establish, through evidence given by bank executives and board members, the extent to which the findings outlined above were the reasons for the collapse of the banking industry in Ireland. In particular the Committee examined the following key areas:

The Joint Committee then examined how these key issues were dealt with within the banks and focused on lending practices.

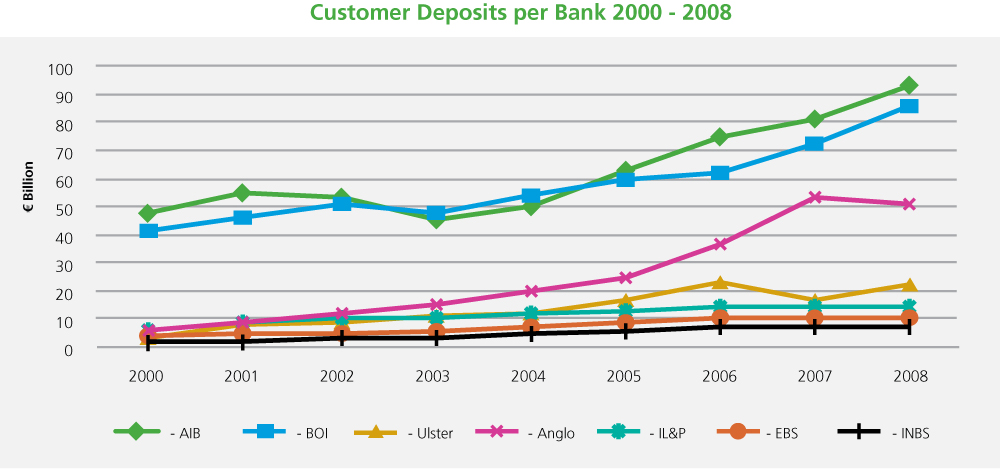

Bank lending had traditionally been funded from customer deposits. This was regarded as a stable means of funding banks since deposits generally stay with a bank. Some financial institutions were completely funded by deposits in the late 1990s.

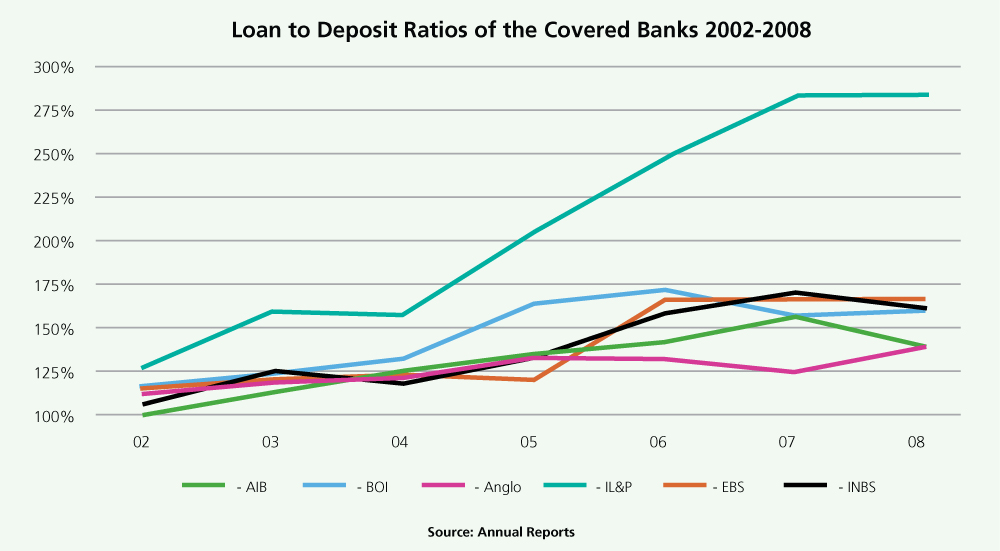

The introduction of the single currency enabled Irish banks to access credit with a low interest rate from the wholesale markets. These markets are an important part of the funding mechanism of banks, but the Irish banks became increasingly dependent on such funding. The Loan to Deposit Ratio (LDR) of the Irish banks which reflects the ratio of the size of lending book to that of customer deposits began to increase. Where the LDR exceeded 100%, it became necessary to borrow from the wholesale money markets to fund lending. Some banks funded their lending primarily through issuing bonds, while others funded their lending primarily through a mixture of short-term deposits and bonds. The Joint Committee explored the growth of such funding with witnesses, and the effect or otherwise that the ability to borrow cheaply from the wholesale markets had on the Irish banking system.

The Loan to Deposit Ratios of the Covered Banks between 2002 and 2008 were set out in the Nyberg Report in the following graph:

Source: Nyberg Report.23

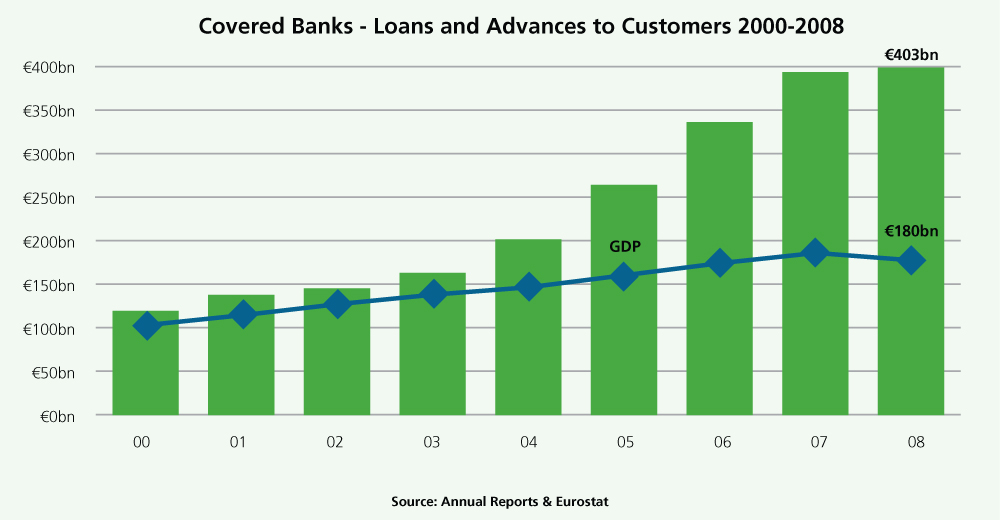

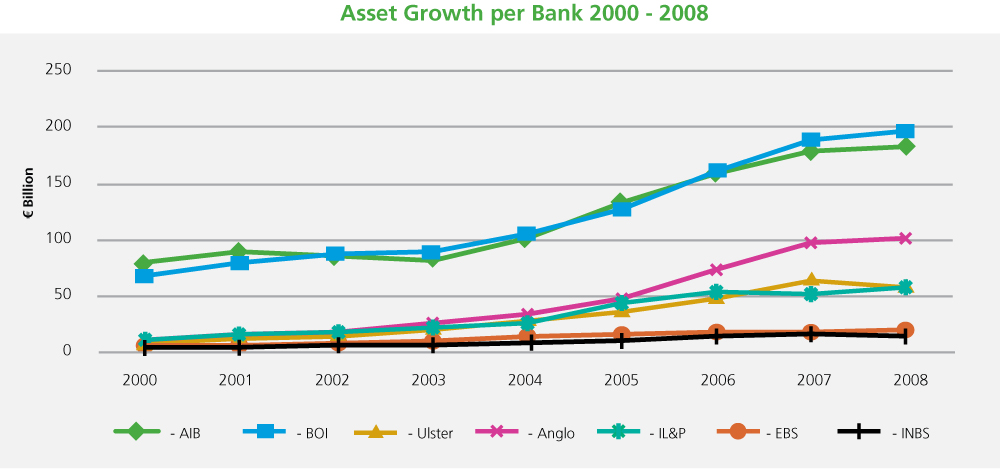

Access to substantial euro denominated liquidity enabled the Irish banks to finance the substantial growth of their loan books from 2002 to 2008 through the increase of debt securities and wholesale deposits. This altered the refinancing pattern of the banks dramatically from 2003 onwards. Customer deposits needed to be supplemented with additional wholesale borrowings to finance the strong credit growth.24

The Irish banks rapidly increased the size of their balance sheets in the years from 2000 to 2008.25 Lending expanded by some 25% per annum, which was roughly twice the rate of growth in the Eurozone as a whole as shown in the following table.26

Source: Nyberg Report27

However, as the financial institutions had insufficient deposits on their books to fund their balance sheet growth, they became increasingly reliant on short- and medium-term funding from the wholesale money markets to provide the liquidity they needed.

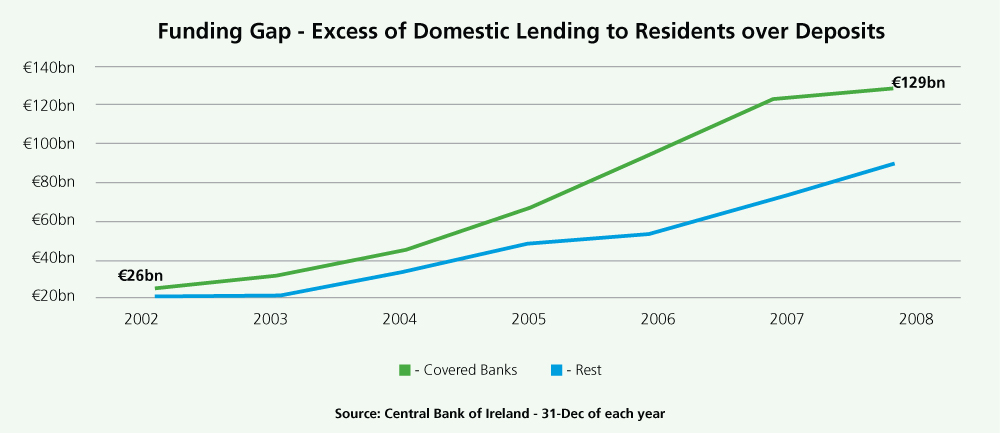

Access to wholesale funding enabled a ten-fold increase in the bond issuance activities of the main Irish banks between 2000 and 2008. Indeed, in the five years to mid-2008 the net foreign liabilities of the Irish banking sector increased from about 20% to about 70% of GDP, and wholesale funding rose to 55% of assets.28

Borrowings on the Irish financial institutions’ balance sheets derived from wholesale sources grew from €26 billion to €129 billion,29 between 2002 to 2008, as shown in the following table, at which stage Ireland had the highest Loan to Deposit Ratio in the European Union.

Source: Nyberg Report30

By 2007, due to growing concerns about the risks of inter-bank lending, available liquidity became more difficult to obtain across Europe, and indeed worldwide. The ECB acted to provide additional liquidity to the Eurozone from August 2007, through the injection of substantial funds.

Philip Lane said to the Joint Committee:

“During 2007-2009, the availability of eurosystem liquidity provided an important buffer during the international financial crisis: banks in the euro area could replace private funding with central bank funding. For banks with insufficient eurosystem-eligible collateral, national central banks could also provide emergency liquidity assistance (ELA), within the framework set out by the eurosystem.”31

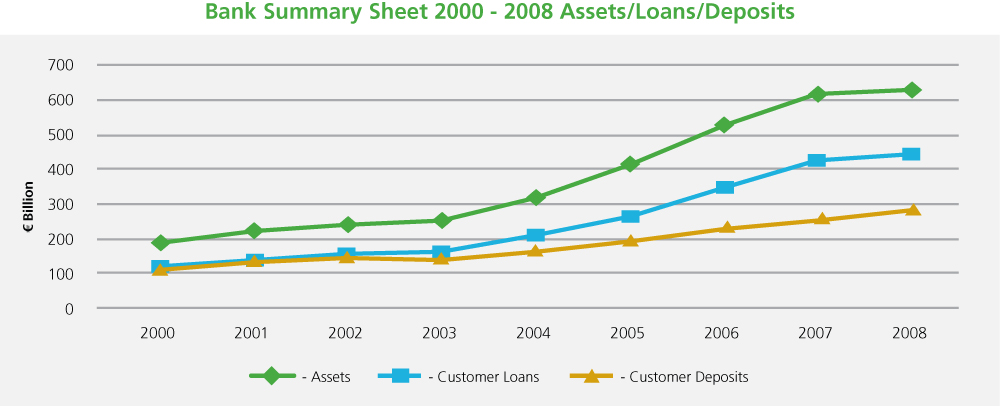

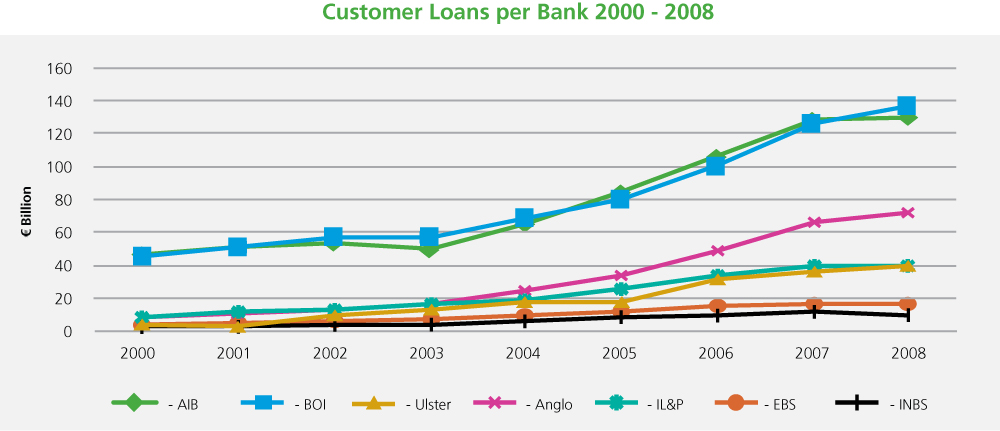

The Joint Committee shows the key figures of the Financial Institutions between the years 2000 to 2008 below. See graphs and table below:

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

AIB |

46 |

129 |

180% |

|

BOI |

45 |

136 |

202% |

|

ULSTER |

4 |

39 |

875% |

|

ANGLO |

8 |

72 |

800% |

|

IL&P |

8 |

40 |

400% |

|

EBS |

4 |

17 |

325% |

|

INBS |

3 |

10 |

233% |

|

TOTAL |

118 |

443 |

275% |

Source: All figures taken from published Annual Reports. IL&P figures include figures for banking activities only. For 2005-08 the Assets figures are extracted from consolidated IFRS statements.

The degree of dependence on wholesale markets of each of the banks is set out below.

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

AIB |

46 |

129 |

180% |

In 2003, AIB had a LDR of 114% and this grew to 143% in 2006.32 In a proposal to revise the Adjusted Loan Deposit Ratio in the June 2007 forecast, a 2007 figure of 162% was indicated for LDR on a balance sheet that had moved from €78.2 billion to €188 billion in the same period. The presentation to the AIB board, dated 21 June 2007,33 highlights the use of an Adjusted Loan Deposit Ratio, which AIB had been using since 2004, to introduce amendments to the use of Mortgage Trust Promissory Notes, Issued Covered Bonds and Wholesale Funding (greater than one year) as adjusting factors.

John O’Donnell, former Chief Financial Officer of AIB, said that the bank’s level of wholesale funding was in line with peer banks and suggested long-term wholesale funding “may be the most reliable and stable funding available in a crisis.” He noted that the bank was conscious of the “greater risks”of shorter-term wholesale funding and steps were taken to put a proportion of it on a longer duration. He said that, prior to the crisis, AIB’s funding profile would not have been considered high risk and referred to a 2007 Standard & Poor’s Report. To his knowledge, no more than 20% of the bank’s funding would mature in a year.34

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

BOI |

45 |

136 |

202% |

Ronan Murphy, former Group Chief Risk Officer, BOI, noted the “super-abundance of liquidity”after 9/11 and prior to the liquidity crisis of 2007. He noted that the bank’s “Strategy 2012”, signed off by the board in July 2006, called for significant growth which could only be funded by access to wholesale funding, which he then believed was “an acceptable and reasonable risk.”35

John O’Donovan, former Chief Financial Officer of BOI, noted the shift from retail deposit funding towards wholesale funding after 2000. He indicated that 41% of the Group’s balance sheet was sourced from the wholesale markets in March 2008 and the expansion of the bank’s loan book, particularly into areas that did not generate deposits, had brought a greater reliance on wholesale funding. He said that the funding was diversified by geography and product line and that the risk was mitigated by the extension of the maturity profile. However, these measures were not sufficient to cope with the closure of wholesale markets.36

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

Anglo |

8 |

72 |

800% |

In his opening remarks, Tom Browne, former Managing Director of Lending Ireland, Anglo, said:

“over the ten years to 2005, Anglo Irish Bank had transformed from being a small player in the Irish marketplace to becoming a serious player in terms of market share in chosen segments in Ireland.”37

The bank achieved this, in his opinion, by reason of a number of factors:

“a very active long-standing client base, many of whom had become the leading players in the property development and investment sectors; very strong customer loyalty across the core client base, which ensured a high level of repeat business for the bank; and an economic environment with low interest rates and wholesale bank funding at unprecedented levels.”38

He pointed out that throughout the early part of 2007, while there was no indication of stress

“…the pressure which emerged ultimately, post the Northern Rock issue, demonstrated that the funding base was not sufficiently wide, deep or stable to underpin the scale of the loan book.”39

Matt Moran, former Chief Financial Officer, Anglo, pointed out that the bank’s funding model had a limited degree of geographic diversity with the main sources from within the Irish and UK markets. He said that the bank, not being a retail bank with a wide branch network, did not naturally have a customer funding franchise linked to current accounts. He said that the availability of money and the different sources available in capital markets was unprecedented post the introduction of the Euro. He also said:

“The ample supply of money made it relatively easy for banks to access funding. This is undoubtedly one of the core factors which set the environment for the root cause of the crisis experienced across Europe. Its impact should not be underestimated.”40

He went on to point out that following the collapse of Lehman’s Brothers, the bank was

“…far too small to control its destiny in this area. The Market set the mix, maturity profile and cost. From the 15 of September 2008 onwards, it was very difficult to raise any funding in the markets”41

Peter Fitzgerald, former Director of Corporate and Retail Treasury, Anglo Irish Bank, pointed out that “Anglo was always attracting funds that were highly mobile in nature. In hindsight this was a risk that quickly escalated in line with the rapid growth in that business.”42

He acknowledged that this growing dependence on wholesale funding was an issue and that it was obvious to them in late 2007, early 2008. He said:

“…I think one of the messages from the 2008 results was that the aim of the bank, predominately through the customer deposit side, was to be 100% loan to deposit ratio by 2011.”43

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

ULSTER |

4 |

39 |

875% |

RBS Group Treasury assumed responsibility for treasury and balance sheet management and undertook to meet the capital and funding needs of Ulster Bank directly. This effectively took control of the liquidity funding out of the hands of the Irish entity and the capital funding requirements were viewed in the context of the overall RBS Group situation. By September 2007, 45% of Ulster Bank’s group funding was provided by wholesale markets.44

The former Group Finance Officer, Michael Torpey, said “… I very much regret that, like so many others, I did not foresee… the extent or duration of the turbulence in wholesale funding markets.”45

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

IL&P |

8 |

40 |

400% |

The Nyberg Report found that “IL&P was very dependent on wholesale funding”and it was noted that:

“IL&P had the backstop of being able to use residential mortgages (which are deemed to be less risky than commercial mortgages) to access ECB funding when wholesale funding markets became less accessible.”46

David Gantly former Group Treasurer of IL&P, told the Joint Committee that:

“Irish Life and Permanent’s balance sheet differed from the two main banks in that 85% of the assets comprised of residential mortgages, which were highly liquid in normal market conditions.”47

He explained that the bank’s funding “was broadly split into three thirds: long-term debt, customer accounts and short-term wholesale debt.”48

Towards late 2007, however, the bank was increasingly aware of potential problems arising from its exposure to wholesale market funding. David Gantly said that the bank moved to prepare pools of mortgage assets as a contingency measure. He said in his witness statement: “This is exactly what we would have done if we were to prepare a portion of the mortgage portfolio for a conventional securitisation.”49

Despite having the ability to securitise these assets, the bank found itself in severe difficulties during the crisis. David Went, former Group Chief Executive of IL&P, informed the Joint Committee:

“Events subsequently proved this funding model absolutely inadequate. External events together with negative views on Irish credit portfolios ensured that very rapidly all capital markets were closed to IL&P with the disastrous effects that we now know. The error here was clearly failing to recognise Peter Nyberg’s point that in the capital markets there is only one counter-party and hence if one source closes to a borrower all will close simultaneously.”50

He was asked by the Joint Committee “were you aware of the issues and did you regard this as a fundamental risk or not?” to which he replied:

“Well, we were clearly aware of the issues because we reviewed on a monthly basis the make-up of our funding portfolio. However, we concluded that for us the primary thing that we looked at was the extent to which customer deposits, long-term debt and securitisation funded our total loan book. And that was about two-thirds of it was funded through that, and these were seen as relatively stable source of funding … and that proportion had been relatively stable over a number of years.”51

On the issue of wholesale funding, he told the Joint Committee that Irish banks “had been somewhat constrained in terms of their access to funding”52 before the Euro but after its introduction “they now had access to the second, or one of the two widest and deepest and most liquid markets in the world.”53 He concluded that the access the Euro gave Irish banks to wholesale funding “was seen as a very attractive proposition.”54

“The Group’s lending book grew aggressively from €12.9bn in 2001 to €39.2bn in 2007. This growth was largely funded through the wholesale markets … customer accounts only grew from €9.5bn to €13.6bn in the same period… The Group’s position was highly precarious in 2008 due to its high level of short term funding and therefore its high loan to deposit ratio.”55

IL&P did not go down the commercial property route to growth. However, it did fund the expansion of its loan portfolio to a noticeable degree through the wholesale markets.

David Went also told us that the bank, as part of its contingency plans,

“assumed that the regulatory authorities would be aggressive in providing support to the system, making Central Bank borrowing effectively the swing factor in ensuring the survival of the institution.”56

It would appear that, for IL&P at least, the assumption that the regulatory authorities and the Central Bank would not only have, but would implement, a contingency plan formed part of their own assumptions about what a worse-case scenario would actually entail.

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

INBS |

3 |

10 |

233% |

John Stanley Purcell, Director and Secretary, INBS said:

“INBS was funded in equal amounts from customer accounts and the wholesale market…The funds raised on the wholesale market extended the maturity profile of borrowings”57

When Michael Fingleton, former Chief Executive, INBS was questioned in relation to access to wholesale funding at the time of the Guarantee he said “We in 2008 and prior to the guarantee, had no need to access the…wholesale market.”58

Michael Walsh, former Chairman, said that, with the benefit of hindsight, “I believe that the difficulties which the Society subsequently encountered and the associated losses arose from a combination of factors.”59 He outlined these as the bubble of cheap credit, hyper competition, markets freezing and inability to finance. He stated that the inability to refinance due to:

“…the resulting drying up of liquidity in the international inter-bank markets (Lehmans, Bear Stearns) meant that banks could not source adequate funding and therefore the Society’s customers found it increasingly difficult to refinance their short term loans from the Society with other lenders as had been traditionally been the case.”60

| Customer Loans (€billions) | 2000 | 2008 | % Growth |

|

EBS |

4 |

17 |

325% |

Fergus Murphy, former Group Chief Executive Officer at EBS said in evidence that the society had traditionally pursued a conservative funding strategy, but the impact of the contraction in the global funding markets that began in mid-2007:

“…was significantly impeding EBS’s access to the wholesale and corporate funds…The complete dislocation of the wholesale funding markets in the latter half of 2007 prevented EBS from securing any long term funding.”61

Fergus Murphy explained:

“when this influx of liquidity across the world churning around was taking place we received, and our financial institutions received, more of that liquidity than we should have and it meant that Irish banks were able to go to the wholesale markets in a way that they never were before. For example, in 1998, the EBS balance sheet was 100% funded by retail deposits. When I took over in 2008, it was 26% funded by retail deposits. So what had happened in the interim was the effect of what I was just describing.”62

Faced with increased competition, some of the financial institutions responded to market pressure in order to protect their customer base and market shares. Management in these banks were also concerned about peer group comparisons.

Michael Walsh commented on market share:

“if you look at [total] market shares … basically Anglo increased its market share and AIB and Bank of Ireland decreased. But if you were to actually look at it in terms of […] property and construction, you’ll find that, you know, the two big lenders into property and construction in this country were AIB and Anglo. Bank of Ireland is less than half of either of those.”63

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Michael Fingleton said:

“following the entry of Bank of Scotland and the other foreign-owned banks into the market in 1999 it became increasingly difficult for the society to compete in the residential loans market.”64

In particular, evidence was given to the Joint Committee to the effect that hitherto established lending policies were relaxed, or re-interpreted, as mere “guidelines”in the rush to secure new business at AIB. For example, Jim O’Leary, former Independent Non-Executive Director of AIB, stated that:

“There was no doubt that the activities of competitors influenced decisions made by AIB…in the area of mortgage lending, for example, in order to protect market share, AIB felt compelled to relax its underwriting standards, (most obviously in respect to LTV ratios) over time, in response to aggressive competition.”65

When asked to compare the growth of the development, property and construction book in AIB as against BOI and Anglo, Eugene Sheehy, former Chief Executive Officer, AIB, responded as follows:

“I note the comparators you’re making and I’m only going to talk about a comparison between ourselves and Bank of Ireland because that’s the only equivalence. They were a retail commercial bank; so are we. There was a slight difference in our customer base. We were much heavier than they were in the SME sector and property and construction was widespread. We had, you know, in the … we had very large customers and then we had 650 customers who had property and construction loans of over €1 million, so it wasn’t … it was very broadly spread and reflected our franchise and the nature of our franchise.”66

Bank of Ireland, in turn, saw AIB as their “most significant competitor.”67 The evidence given to the Joint Committee by Bank of Ireland included an analysis carried out in 2005 of all its competitors across the retail spectrum.68 This analysis, which focussed on retail banking, set out the view Bank of Ireland had of others such as Ulster Bank, Danske, BoSI and Rabobank but it did not refer to Anglo.

However Richie Boucher, Chief Executive Officer, BOI, said, in his evidence to the Joint Committee, “certainly, we did compete with Anglo at the higher end…corporate property market.”69

Brian Goggin, former Chief Executive Officer, BOI, gave evidence that:

“Bank of Ireland had a market share across most of its product lines, ranging depending on which product line one would pick, but market shares ranging from kind of high teens right up to mid-30s, mid-30s in the case of working accounts or current accounts.”70

Tom Browne addressed the question of Anglo and market share in his evidence. He said:

“Over the ten years to 2005, Anglo Irish Bank had transformed from being a small player in the Irish market place to becoming a serious player in terms of market share in chosen segments in Ireland. The success of Anglo over the ten-year period to 2005 was reflected not just in the growth of the loan book, but also in year-on-year increases in earnings and a strong market rating.”71

He also said that competition grew in the domestic banking sector and that “this competition came from existing universal banks in Ireland and from emerging foreign lenders in the market.”72

Tom Browne also referred to a decision taken by the board of Anglo in early 2006:

“on the basis of management advice, to change its lending policy reflecting the concerns we held about the acceleration in asset values and given the growing intensity of competition.”However, he said that “the failure to more forcibly implement the policy decision […] was a serious mistake.”73

Despite the fact that Anglo “could see from early 2006 that the market was getting seriously overheated”,74 the bank did not strictly adhere to the board’s decision.

Robert Gallagher, former Chief Executive Corporate Markets Division, Ulster Bank said that “the bank’s strategy was to become a third force in the Irish universal banking market, to challenge the dominance of the big two.”75

Upon further questioning with regard to Ulster Bank acting “in support of the Group’s ambition to be the Number One Bank in Ireland”Robert Gallagher said that “We had … we had an ambition for that, yes.”76

In addressing that same point, Michael Torpey said:

“it is entirely acceptable from a business perspective, in my view, that a small challenger can seek to grow significantly more rapidly than the general marketplace and significantly more rapidly than a competitor’s, in the interest of bringing competition to the marketplace and growing its position relative to the incumbents.”77

He also dealt with the question of how the bank attempted to grow market share, by saying:

“The assumptions we made, unfortunately, were the wrong assumptions and it … it is unfortunate and in every respect - and it’s something that I very much regret - that we didn’t in fact challenge sufficiently on the variety of assumptions that underpinned the expectations of continuing growth in the market.”78

David Gantly was asked about the bank’s position on market share. He said that “a very stated objective of the group to be the No. 1 provider of retail financial services so I think there was an element of cross-sale seen in this, to be fair, as well.”79 David Went also said that IL&P “decided essentially to be, you know, a mortgage lender, a plain vanilla mortgage lender.”80

In expanding on the business model, David Went said:

“The adopted strategy won market acceptance at the time, and appeared logical focussing on lower risk widely spread portfolios of lending in a home market where we had operated successfully for many years and had substantial market presence while exiting a number of overseas investments that were high risk and sub-scale in order to invest capital in Ireland that appeared to offer substantial opportunities.”81

In his written submission to the Joint Committee, Michael Fingleton said that:

“The Society was not focused on increasing its market share but concentrated on lending to customers who were well known to the Society and who had been tried and tested and performed successfully in the past.”82

Michael Walsh, corroborated Michael Fingleton’s evidence, when he said in his statement that “Hyper Competition: progressively from 2004 onward larger financial institutions piled into the market in which the Society had operated since 1992.”83

In explaining the effect of the entry of foreign-owned banks into the market, Michael Fingleton said: “They undercut everybody, competition intensified, our book was attacked and we, effectively, couldn’t compete …”84

Fergus Murphy said, to the Joint Committee, that his view of EBS’s approach to market share was that it was driven “More by survival than market share.”85

The society, according to Fergus Murphy’s evidence, had concerns about its future as a mutual society. In the early 2000s “EBS were looking at options in terms of was there another way to preserve the mutual or mutual-like environment and code and heritage and, at the same time, get access to a bigger balance sheet and a more powerful engine…”86 Interestingly, he did not see these concerns purely in terms of market share.

EBS was using land and development lending as part of a strategy to hold residential mortgage market share, and this strategy, in the opinion of Fergus Murphy, was a factor in its demise as an independent society.87

Former Finance Director at EBS, Alan Merriman, gave evidence regarding the problems the society faced in maintaining its mortgage lending market share. He told the Joint Committee that two of the society’s core areas of business were the mortgage refinance market and the first-time buyer market, and that it found itself under increasing pressure from its competitors for market share in these areas. Alan Merriman noted that:

“… EBS as a traditional building society, having in an environment where it was one of the few players in a normal mortgage market, now found itself in a market where both ends were being very aggressively competed for.”88

The issue of increased competition was also discussed by Fidelma Clarke, former Chief Risk Officer and Company Secretary, who said:

“I think I would and have described it as excessive competition. Absolutely there was excessive competition in the market, which led to downward pressure on the society’s core business, which led it to take decisions about what it could do to remain viable…”89

Having seen the increased use of wholesale market credit by Irish financial institutions, the next question to ask was: to what purpose was this credit put?

It is no secret to say that in the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, Irish financial institutions were over-concentrated in real estate lending, both commercial and residential, at home and abroad. The purpose of this section is to summarise the evidence the Joint Committee heard in relation to commercial real estate credit activity, and to decide whether or not it played a systemic role in the crisis experienced by Irish financial institutions in late 2008. Whereas the focus is on the engagement or otherwise of the financial institutions in this market, rather than the market itself, there is still a need to give a brief overview of the market for clarity. There is more to real estate than home mortgages.

As can be seen later in the report, the transfer of loans from the covered institutions into NAMA crystallised losses in the banks. These losses were covered by government recapitalisation. NAMA had commercial property transferred onto its book, as can be seen in Chapter 9. The total par value of these loans was €74.4 billion for which NAMA paid €31.7 billion. Residential property only consisted of 16.5% of the latter amount, which is similar to office developments which made up 16.6% and hotels alone accounted for 9.6%. Of the loans that remained on the banks’ balance sheets, commercial real estate had an impairment rate of 56.9%90 which was over three times that of residential mortgages and over twice the average of all impaired loans.

The issue of commercial real estate lending and its impact on individual banks was discussed with the bank economists.

Pat McArdle, former Group Chief Economist, Ulster Bank, said: “However, the real problem was commercial and not mortgage lending, and this was not adequately stress tested.”91

Later on he said:

“But let’s assume that it was okay because no one ever reported these stress tests were going to cause any Irish banks to collapse, you know, we never got any inkling of that. So the banks, some banks anyway, Ulster Bank had stress tested for very significant house price falls and there was no problem. The problem was in the commercial mortgage book.”92

Dan McLaughlin former Chief Economist, Bank of Ireland, said: “Plus, the major problem for the Irish banks wasn’t just Irish commercial property; US commercial property prices fell 40%, and UK commercial property prices fell 35%.”93 He said, subsequently:

“I would point out is [sic] the major losses for the Irish banks were not in residential property, they were in commercial property … in commercial property. Not many people, if I recall, wrote anything about commercial property, and that was what caused the damage for Irish banks’ profitability and caused them to require significant capital inflow … injection from the State, not residential property.”94

He also said:

“I think what happened for all of the banks, in 2008, 2009, was that having commercial property in different jurisdictions didn’t prove a very good risk diversification strategy, because in a crisis, unfortunately the correlations collapsed to one. In other words, they all collapsed together, and that is a rare phenomenon but that’s what happened.”95

Later on Dan McLaughlin said: “I think just factually it is the commercial property price falls, asset price falls that opened up the huge capital losses in most of the banks.”96

When asked, if house prices had not fallen but commercial property had fallen to the extent it did (67%), whether the banks would still have needed the amount of capital provided by the Irish state, Dan McLaughlin said:

“Well a lot of it, yes. They didn’t get the capital to cover residential mortgage losses because they haven’t put it in the results that they’ve had massive losses in residential mortgages.”97

John Beggs, former Chief Economist, AIB Global Treasury, said:

“We had no information or very little information about what was happening in commercial property. We’ve done a lot of talking and analysis around housing because we had monthly statistics, we had population. When it came to the commercial side, we didn’t have that information. So we were acting in a very, almost naive way in that we didn’t have full information.”98

When asked if he agreed with the opinion that commercial property broke the banks, John Beggs said:

“Yes, I do, based on the sort of analysis and the way they are thinking about it and looking at it. I mean, it wasn’t house prices that ended up requiring the additional capital… It was on the commercial property book, which had grown dramatically in the years leading up to the … to the banking crisis.”99

The then Taoiseach Bertie Ahern agreed with this assessment. He said:

“I’m just talking about the debate - in the residential side. I mean, look what happened in the commercial property side. I mean, there was where the madness really took place…”100

It is clear that commercial property loans were one of the fundamental fault lines in the Participating Institutions which led to them being rescued by the Irish State. A characteristic of this lending strategy was that it was, for the most part, concentrated within a very small number of borrowers.

In relation to the Irish real estate market, the Joint Committee heard evidence from John Moran, Managing Director of Jones Lang LaSalle Ireland. He started off by giving an explanation of the market:

“The Irish retail real estate market is made up of various components. There is the residential market, the development land and agricultural market, the investment market and the various occupier markets such as offices, retail, industrial, hotels and licensed and leisure premises.”101

He went on to give an overview of the Irish commercial real estate market from the perspective of Jones Lang LaSalle, which specialises in that market:

“Up to 2008 the commercial real estate market was growing strongly. There were increased levels of purchasing, leasing and construction activity. Ireland’s economy was performing well with GDP and employment driving the expansion. It is worth remembering that, at that time, we were the fastest growing economy in western Europe, the second wealthiest economy on a per capita basis measured by GDP and we had the fastest growing population in Europe. During that period unemployment averaged just over 4%, which was effectively full employment. That is important because the real strength in occupier and investor demand is what was supporting the property market. That demand was driving activity levels and increases in values and the capital values of Irish commercial investment property increased by 72% in the five-year period up to 30 September 2007, the date we define as the peak of the market in terms of value appreciation. Property yields were at record levels, which was a reflection of both the strong investor demand and the availability of significant amounts of debt.”102

A supporting document from Jones Lang LaSalle, provided to the Joint Committee by John Moran, stated:

“Between 2004 and 2008 almost €8 billion worth of commercial investment property was sold in Ireland. 2006 was the peak year for investment volumes, with €3.6 billion traded in 12 months. For context, this compares to the previous record of €1.2 billion in 2005 and an average of €768 million per annum between 2001 and 2004.”103

The document then went on to make a small but significant observation: “In addition to domestic spending, there was also considerable Irish investment activity overseas, particularly in the UK and continental Europe.”104

In other words, according to Jones Lang LaSalle, the size of the Irish real estate market in the years leading up to the 2008 crisis was not the sum total of Irish developer investment in real estate, and neither should it be assumed that the Irish commercial property market was the sum total of credit advanced by Irish financial institutions alone for real estate investment purposes during the period under discussion.

Three key developments in the residential property market are considered in this section: Buy-To-Let Mortgages, 100% LTV Loans and Tracker Mortgages.

As the property market became ever more buoyant, many of the banks’ retail customers were able to purchase a second or more properties leading to a significant increase in the buy-to-let market. This type of mortgage became more accessible for borrowers with the introduction of interest-only repayments for one, two or three years. When applying for one of these loans, an applicant would generally be permitted to use the equity of other properties that they owned as security.

Nyberg identified105 two risks associated with the buy-to-let market that are not associated with mainstream residential lending:

Richie Boucher, Group Chief Executive, BOI, stated that the buy-to-let lending “hadn’t been seasoned”in the Irish context and consequently “there hadn’t been sufficient experience of what would happen in a downturn.”106

In 2005 Ulster Bank through First Active were the pioneers in offering 100% mortgages generally (i.e. applicants could borrow up to 100% of the purchase price of a property). As the purchase of property was not contingent on the borrower having to provide any capital, the bank bore 100% of the risk. To explain why Ulster Bank made 100% mortgages available in the first place, Cormac McCarthy, former Group Chief Executive and Director, said:

“…from a competitive position, we were losing share of the first-time buyer market because others were doing 100% mortgages. The second thing was we had seen customers who were to try and get the deposit for a house, were extending themselves on personal loans and credit cards, which is not the right way for people to find deposits for houses.…”107

Some of the banks were less enthusiastic about the 100% mortgage as a product. In July 2005, David Went, the Group Chief Executive of IL&P, sent a “File Note”108 to the other executive directors in the bank, in which he stated that he had spoken to the Regulator and “expressed reservations about the introduction of this product to the market.”He told us “…we concluded, having reviewed the options and having reviewed the risks that were inherent in this, we concluded that we had no option but to proceed.”109

Similarly Brian Goggin stated that Bank of Ireland was a “reluctant follower”and that in order to protect its franchise, the bank offered 100% mortgages initially to professionals and then broadened the offer to first-time buyers.110

Another product innovation within the banking sector was the introduction of tracker mortgages. Banks offered tracker mortgages at a fixed rate above the ECB rate. They used this product as a method to gain market share. Tracker rates were considered stable and the commercial Irish banks could access low cost funding directly from the wholesale markets to fund their needs.

When asked if BOI thought it was going to make money from tracker mortgages, Richie Boucher said: “We had a presumption, I think, that we would always be able to borrow at or near ECB rates.” He then said that this presumption was:

“A very big mistake. You must always price your product based on the cost of your raw material, not of what you presume you might buy it. I don’t think a farmer would sell milk on the basis of what he thinks it might cost. You know we made a basic misassumption of not aligning the pricing of our product to the cost of the raw material. We presumed we could get the raw material and we guaranteed the customer that we always thought we could get the raw material at different price … it transpired we couldn’t.”111

John O’Donnell, former Finance Director of AIB, stated that he “believed the risk was known and understood, albeit historically it had not been significant.”112

Ethna Tinney, former Non-Executive Director EBS, stated in her evidence to the Inquiry:

“And the volumes of tracker mortgages that, therefore, that we were attracting blinded us to the dangers of what would happen in terms of depressing the margin and so the final outcome … we can’t afford the tracker mortgages…”113

John Stanley Purcell was asked the following by the Joint Committee:

“Mr. Purcell, in the Project Harmony report, it would show that the society had a concentration of loans in the higher risk development sector, a concentration of loans in the higher loan-to-value bands, a concentration in its customer base – the top 30 commercial customers, for example, accounted for 53% of the total commercial loan book – and a concentration in sources of supplemental arrangement fees, representing 48% of profit in 2006. Indeed, 73% of those fees came from just nine customers. Did the board ever consider or did they become concerned or did they discuss those levels of concentrations and the correlation between them and whether or not they could increase the risk to the society’s business model?”114

In response, he said: “The board were aware of the concentration. The large exposures report would be produced and it would be a board document.”115

In her written statement, Niamh Brennan, former Non-Executive Director with Ulster Bank, wrote:

“In retrospect, it is now clear that growth in lending and, in particular, lending to the property development and construction sectors made Ulster Bank, like other Irish banks, vulnerable to a collapse in property values.”116

It is clear that a feature of lending to the property sector during the boom years was cross-bank lending whereby a number of different banks lent money to the same borrower.

In his evidence, Frank Daly Chairman of NAMA gave evidence that NAMA’s impression was that the banks seemed to have been acting “almost in isolation”from one another. “They didn’t really have much interest in what a particular client’s exposure was to another bank across the system.”117 NAMA’s view was that, not only did the banks not have sight of a particular client’s exposure to another bank across the system but also, “they didn’t really have much interest.”118 Frank Daly was of the view that retaining the client was undoubtedly a key factor: “there was an emphasis on a kind of relationship lending as much as lending for particular projects that actually seemed feasible.”119

Pat McArdle said that ‘cross borrowing’ by developers between banks “wasn’t known to me and I suspect wasn’t known to the banks either”, before concluding “so I think that was a key factor [in the problems that materialised].”120

Apart from the clear need for effective regulatory oversight, the Joint Committee is of the view that the banks had a prudential duty to themselves to inquire, challenge and assess hidden risks arising from multi-bank borrowing by major clients.

Fintan Drury, a former Non-Executive director of Anglo Irish Bank, pointed out in his statement that:

“The property-related lending strategy of Anglo Irish Bank achieved exceptional returns over the period 2002 – 2008 and no one questioned their appropriateness over those years when the bank was revered by shareholders, analysts, rating agencies and commentators in Ireland and overseas.”121

He told the Inquiry that Anglo Irish Bank “… was, you know, clearly it was a monoline bank, that’s what it did”and in terms of investment property lending he believed that “somewhere between 80% and 90%”of the bank’s loan book related to property investment activities.122

He continued:

“I was aware that there was a relatively small … that the ratio, if you like, in terms of the number, a relatively small number of clients who had quite a significant percentage of … of the lending, yes. Was I concerned about that? Not particularly.”123

Matt Moran told the Inquiry:

“Concentration risk, amongst a small number of developers, partly due to the size of the economy, is now understood to have been too high and the ready availability of funding to banks led to too high a concentration of activity in such a small market.”124

|

Table provides a breakdown of all debtor connections by size of nominal debt exposure. It should be noted that many of the debtors are also indebted to financial institutions which are not part of the NAMA scheme |

|||

| Nominal Debt | Number of debtor connections | Average nominal debt per connection €m | Total nominal debt in this category €m |

|

In excess of €2000m |

3 |

2,758 |

8,275 |

|

Between €1000m and €2000m |

9 |

1,549 |

13,945 |

|

Between €500m and €999m |

17 |

674 |

11,454 |

|

Between €250m and €499m |

34 |

347 |

11,796 |

|

Between €100m and €249m |

82 |

152 |

12,496 |

|

Between €50m and €99m |

99 |

68 |

6,752 |

|

Between €20m and €49m |

226 |

32 |

7,180 |

|

Less than €20m |

302 |

7 |

2,117 |

|

Total |

772 |

96 |

74,015 |

Source: NAMA125

Interest roll-up refers to the practice whereby interest on a loan is added on to the outstanding loan balance ( “rolled-up”) where it effectively becomes part of the loan capital outstanding and accrues further interest. “Rolling-up”interest would generally allow a borrower not to repay interest as it falls due, but this would be done without placing the loan in default.

Of the €74.4 billion worth of loans which were transferred to NAMA, interest which had been rolled up amounted to €9 billion.126 The breakdown of the interest roll-up figure estimated by NAMA for the Participating Institutions was as follows:127

The provision of an interest roll-up facility to a borrower arose in two ways, either by an “interest repayment holiday” being agreed in advance between the bank and borrower or where the borrower had not been able to make a loan interest repayment and the accrued unpaid interest was added to the outstanding loan principal.

Michael O’Flynn, Founder and Managing Director, O’Flynn Construction, gave evidence that the banks’ practice was to allow interest to accumulate and be paid out of either the proceeds of a sale or rental income. The banks generally permitted such roll-up only for the limited period required to bring the project to market. The banks benefitted from a higher amount of interest and borrowers benefitted from not having to pay interest until the development or construction project had been completed.128

In his evidence, Sean Mulryan, Chairman and Chief Executive, Ballymore Group, explained the concept and practice of interest roll-up in the following terms:

“In either a land or development scenario … interest is either cash serviced from borrower or shareholder equity or rolled up until ultimate proceeds are generated … Ballymore almost always requested interest roll up facilities over the term of the loan. Such was the competition in the lending market during the period 2001 to 2008, in Ireland and overseas, that interest roll up facilities were frequently offered by financial institutions.”129

Brian Goggin gave evidence that “…roll-up of interest in a land bank transaction was perfectly in accordance with policy.”130 Eugene Sheehy said “…there was interest roll-up because there was cash flow problems generally in the second half of ’08.”131

NAMA’s evidence to the Joint Committee was that, on acquisition of the property-related loans, the existence of interest roll-up per sewas not surprising. It was the extent of interest roll-up, especially cases where “new loans were being created to take account of the rolled up interest”that took NAMA by surprise.132

Tom Browne was asked if interest roll-up had left Anglo exposed in the downturn. He acknowledged that it had and that it was a large concern for the bank. As a result of Anglo’s concern over property related loans, the bank changed their policy on interest roll-up in 2006 in an attempt to curtail this activity.133

Interest roll-up benefited both banks and borrowers when market conditions were positive but, a serious difficulty arose when Ireland’s property market crashed and borrowers became unable to repay the principal into which the interest had been rolled up.

Gary McGann, Independent Non-Executive Director at Anglo, when asked in relation to interest roll-up “with such a narrow field of individuals did the bank consider that in terms of risk”,answered “Not specifically.”134

A “Statement of Affairs” is a summary of a borrower’s assets, liabilities and overall net worth.

Brian Patterson, former Chairman of IFSRA, said:

“after the crash, it emerged, as we know, that some large developers had never been asked by their bank to provide a statement of affairs nor had the bank properly assessed their net worth.”135

Brendan McDonagh gave evidence that NAMA found that statements of affairs had frequently been relied upon by banks to provide comfort that a debtor’s financial position could support new lending and service liabilities, but that these were not always audited and were instead often self-certified by the borrowers themselves.136

Reliance on Statements of Affairs was compounded by the fact that the assets of most relevant borrowers were comprised mainly or exclusively of property assets. As market prices had risen in the years up to 2007, the self-assessed net worth of borrowers also appeared to rise; this gave the banks “a sense of false comfort.”137

Frank Daly explained the risk in the following terms:

“…once you begin to rely on personal guarantees then by definition you are relying on the personal wealth of the debtor. If the process by which that personal wealth is assessed is in any way doubtful – in other words if it is done on the basis of Statements of Affairs where the valuation of assets is essentially done by the debtor and maybe not rigorously examined or overseen by the banks – then you are getting into a cross-collateralisation right across the loan book and you are getting into it on the basis again of relationship banking, with not a huge amount of oversight.”138

Michael O’Flynn, however, gave evidence of significant equity invested in the O’Flynn Group developments and also confirmed that the loans of the O’Flynn Group were not secured by any personal guarantee.139

At one end of the spectrum were developers who generally operated to high standards of governance, business case development and financial controls. At the other end of the spectrum were borrowers who lacked critical experience, knowledge and skills.

This classification was shared by a number of the developer witnesses. Sean Mulryan stated there were:

“ordinary people calling themselves property developers, buying properties, not alone in Ireland, in Bulgaria, in Romania, all over the world and in Ireland and building big portfolios on 95%, 100% finance.”140

Michael O’Flynn, stated that there were:

“…part-time developers or people who had gone into the development business without having any understanding of the fundamentals involved.”141

Joe O’Reilly, Executive Chairman, Castlethorn Construction and Chartered Land Group also stated:

“…a number of people came into the business … they weren’t necessarily … they were in other businesses that changed into … that changed into … or they suddenly became a property developer overnight.”142

Brendan McDonagh gave evidence that:

“The banks were quite clearly lending to individuals and companies that, notwithstanding the massive sums involved, had little or no supporting corporate infrastructure, had poor governance and had inadequate financial controls and this applied to companies of all sizes.”143

In his evidence, Frank Daly said that there was also “…lending on hope value to people at the bottom.”144

He added that a substantial amount of that type of borrowing was related to “land which wasn’t even zoned, which had hope value more than anything else.”145 Brendan McDonagh said that in the case of some 600 or so such NAMA debtors, “…very few of them seemed to have any expertise in construction.”146

The CRE sector loan exposure remaining in the Irish covered institutions at the end of 2013 totals €36.5 billion with an impairment rate of 56.9% totalling an amount of €20.8 billion. This issue will be considered further in Chapter 8: Post Guarantee Developments.

| Outstanding loans | Impaired loans | |||||

|

BOI |

AIB |

PTSB |

Total |

Impairment rate |

Impairment loans |

|

|

Mortgages |

51.6 |

40.7 |

29.0 |

121.3 |

17.7% |

21.5 |

|

CRE |

16.8 |

19.7 |

36.5 |

56.9% |

20.8 |

|

|

SME |

13.6 |

13.7 |

27.3 |

25.1% |

6.9 |

|

|

Corporate |

7.8 |

4.3 |

12.1 |

25.1% |

3.0 |

|

|

Consumer |

2.8 |

4.3 |

0.3 |

7.4 |

6.1% |

0.4 |

|

Total |

92.6 |

82.7 |

29.3 |

204.6 |

25.7% |

52.6 |

|

Note:Only five of the six Irish banks participated in the NAMA process. Anglo and INBS merged into IBRC. EBS was acquired by AIB. Source:Annual reports 2013 of banks for outstanding loans; Central Bank of Ireland for impairment rates, there is only a joint impairment rate for SME and Corporate available. |

||||||

Source: Schoenmaker147

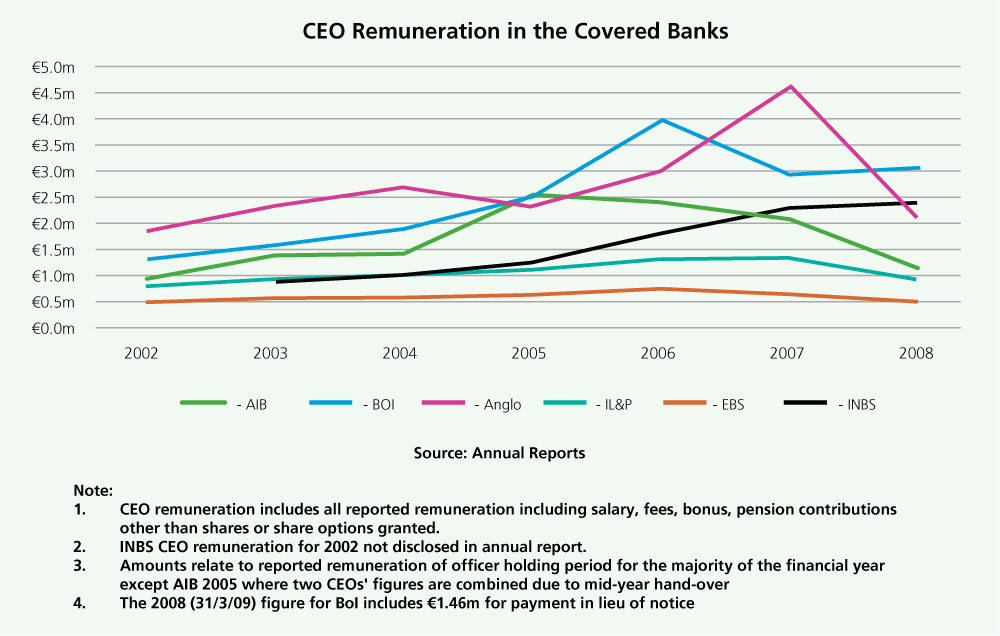

Significant changes in leadership in the banks took place in the years leading to 2007. The remuneration of the senior executives of those boards at that stage should be considered. The Joint Committee was provided with details of the top ten salaries and bonuses paid to the senior executives in each of the six Covered Institutions. We will now outline the position with regard to the CEOs.

The Nyberg Report showed CEOs remuneration in the covered banks as follows:148

| '000 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

|

Anglo |

€1,885 |

€2,346 |

€2,721 |

€2,354 |

€3,015 |

€4,656 |

€2,129 |

|

INBS |

(Note 3) |

€910 |

€1,034 |

€1,269 |

€1,836 |

€2,313 |

€2,417 |

|

AIB |

€940 |

€1,399 |

€1,445 |

€2,563 |

€2,436 |

€2,105 |

€1,152 |

|

BoI |

€1,318 |

€1,594 |

€1,919 |

€2,525 |

€3,998 |

€2,972 |

€3,095 |

|

EBS |

€513 |

€589 |

€601 |

€655 |

€760 |

€678 |

€522 |

|

IL&P |

€822 |

€946 |

€1,025 |

€1,138 |

€1,335 |

€1,362 |

€942 |

The remuneration of the CEO, or person of equivalent standing, at each bank in 2007 was as follows:

| Bank | CEO | Salary & Fees (€'000) | Bonus/Profit Share (€'000) | Benefits (€'000) | Pension (€'000) | Total (€000s) | B/S (€bn) | PBT (€bn) | Employ (’000s) |

|

Bank of Ireland |

Brian Goggin |

1,100 |

2,025 |

1,227 |

*(354) |

3,998 |

188.81 |

1.96 |

15.95 |

|

Anglo Irish |

David Drumm |

956 |

2,000 |

44 |

274 |

3,274 |

96.65 |

1.24 |

1.71 |

|

INBS |

Michael Fingleton |

865 |

1,400 |

48 |

*0 |

2,313 |

16.10 |

0.39 |

0.37 |

|

AIB |

Eugene Sheehy |

916 |

862 |

65 |

262 |

2,105 |

177.86 |

2.51 |

25.89 |

|

IL&P |

Denis Casey |

694 |

617 |

51 |

300 |

1,662 |

59.82 |

0.48 |

5.01 |

|

EBS |

Ted McGovern** |

353 |

290 |

34 |

***201 |

878 |

19.45 |

0.67 |

0.66 |

|

Totals |

4,884 |

7,194 |

1,469 |

683 |

14,230 |

558.69 |

7.25 |

49.59 |

* Pension capped therefore a clawback occurs or zero payment

** Retired 30 September 2007, Compensation payment of €1.87m on early retirement

*** Approximation of pension for year

The average industrial wage in 2007 was €37,726, according the CSO’s National Employment Survey. By comparison, the average senior bank executives in AIB were receiving total remuneration of over 42 times that figure and those in Bank of Ireland were receiving 48 times that figure, in the same year.

The three Executive Directors of AIB, Eugene Sheehy, John O’Donnell and Colm Doherty, former Managing Director of AIB Capital Markets and former Group Managing Director of AIB, shared a total remuneration pot of €5.5 million in 2006, which was an average of €1.83 million each. When Donal Forde, former Managing Director AIB in the Republic of Ireland, is added to these three Executive Directors, the figure increased to €6.4 million, or an average of €1.6 million each. When asked to comment on the fact that the total remuneration for four AIB directors amounted to €6.435 million in 2007, Eugene Sheehy stated that there was no evidence of the bank crisis at that stage - “Well, at that stage there wasn’t any evidence of what was going to come.”149

At BOI the equivalent remuneration figures for Brian Goggin and John O’Donovan in 2005/06 was a total of €3.64 million (averaging at €1.82 million each). With the addition of Richie Boucher, Des Crowley and Denis Donovan to the Board in 2006/07, the overall figure increased to €8.98 million, which averaged at €1.79 million each.

At Anglo the total figure for their five Executive Directors in 2007 was €8.5 million, giving an average of €1.7 million each.

In the course of Hearings before the Joint Committee, a number of the senior executives of the Irish banks gave evidence and defended the high remuneration received by them by reference to the independence of the process of determining their remuneration. They were questioned on whether they had been overpaid before the crash and having regard to the huge losses subsequently incurred. None of these witnesses said that their pay was particularly excessive, even though the banks within their charge ultimately exposed the Irish taxpayer to a cost of €64 billion to cover the losses. However, Eugene Sheehy, of AIB, said “The numbers are very high, not justifiable in my view in today’s terms.”150

Similarly when responding to a question regarding bonus payments, Michael Fingleton stated that: “I certainly would say in hindsight they were excessive.”He explained:

“I did not determine my bonuses. They were done by the remuneration committee, which comprised the three, or all the non-executive directors, and they decided what my bonus was.”151

When asked if he had merited his remuneration, Brian Goggin stated:

“I was paid exceptionally well as chief executive of the bank. My remuneration as chief executive and the remuneration of the chief executive was determined by the board. I had no input or involvement in that determination.”

He also said “It wasn’t for me to determine.”152

Richie Boucher said:

“My salary was approved by the Minister for Finance at the time and was voted on by the shareholders who were paying for it and that continues to be the case. Every year I stand before the shareholders to be elected as to whether I stay in my job or not and the shareholders decide what I’m paid. I don’t have anything further to say on that.”153

A number of these witnesses explained how their remuneration packages were determined.

When asked to explain how he ended up with a salary of €2.4 million per annum and how it could be justified, Eugene Sheehy explained:

“…there were a number of components to it and they were scientifically constructed. We had three external consultants who looked at it.”

He also said:

“And if you look at the Nyberg report you will see that AIB was much, much lower…rather than…of the peer group, in terms of size. So, there was a science to it.”

and

“But the actual amounts that we were paid were too high … I mean, when I came from the States I was paid a lot less over there, but they had a totally different philosophy about long-term compensation.”154

Gary McGann gave evidence to the Joint Committee that:

“…the remuneration arrangements in any business, particularly plcs, are based on best practice in the marketplace as advised by the various people who are expert in this area and Anglo Irish Bank’s structure was no different fundamentally than anybody else’s. There are obviously three elements to it - there is salary, there is short-term bonus and there is long-term incentive schemes. And the basis of each of those is against market practices, the quality and the size of the business and the performance of the business.”155

Cormac McCarthy explained in relation to remuneration in Ulster Bank that:

“the salaries and remuneration, remuneration generally was bench marked and there was significant comparability and oversight from Royal Bank of Scotland, not just Ulster Bank. So at any point in time our salaries were independently benchmarked and found to be competitive. Certainly with the benefit of hindsight, Chairman, yes there was an excessive element to things, yes.”156

Some of the evidence presented to us indicated that a number of factors coalesced to bring about excessive reliance on the property market. These include:

1. Increased competition in the banking market

This factor has been explored already and it has been found that increased competition was a significant factor in the issues that arose in the banking sector.

Brendan McDonagh, as Director of Finance, Technology and Risk at the NTMA, stated:

“There appeared to be a highly accommodating attitude among financial institutions towards the more prominent debtors and a concern that, if that institution was not particularly amenable, the debtor would look elsewhere for the funding of future projects. Clearly debtors were not slow to exploit the unusual lending market.”157

It was noted in a Bank of Ireland memorandum, dated 28 August 2008, from Group Credit to Group Risk Policy Committee, that

“changes may be merited/required in the interests of protecting our “franchise”/market share…”158 At the end of this memo, Group Credit expressed a warning:

“we are concerned that the proposal to significantly relax Income Multiples may result in an unacceptable level of exposure to High LTV, High Income Multiple FTB’s and it will be important that TMB monitors the quality of new business written under the revised Policy.”159

2. Poor risk monitoring and exceptions to lending policy

As the competition for market share increased over the period, adherence to established policies and procedures, in at least some of the banks, weakened. An AIB report from 2010 noted that during the pre-financial crisis period

“……breaches of policy became common and were treated as routine events even if they were escalated.”160

Evidence was provided to the Joint Committee in relation to exceptions to lending policies. In the case of Anglo, for example, exceptions to group lending policy were running at 26% to 28% of loans approved each month by early 2008 and by July of that year, they reached a high of 42%.161 The exceptions from the policy in the case of mortgage approvals by Ulster Bank, peaked at 40% of loans approved in July 2006.162 Exceptions to mortgage policy in AIB peaked at 30% in 2004 but had reduced to 21% in 2007.163

3. Inadequate Management Information Systems

Evidence was provided that, in some cases, Management Information Systems (MIS) may not have been adequate and/or capable of providing consolidated, insightful information on the status and trends in loan portfolios, especially through filtering sectoral lending by debtor concentrations and accompanying risks. Robust MIS are crucial to providing the necessary information to management. In the absence of such systems, evidence-based decision-making at the institutional level is made more difficult.

Ronan Murphy said in his witness statement: