Back to Chapter 3: The Property Sector

In this Chapter, we explore the state institutions that were accountable for the regulation and supervision of both the banking sector and the financial stability of the state during the period leading up to the financial crisis. We consider the institutions’ roles, powers and the choices that they made during this critical period. We also consider the role and contribution of both international and domestic agencies in flagging and highlighting the emerging risks and growing threats to the Irish economy. These will be covered in three sections:

The availability of accurate and independent analysis of macro-economic and systemic risk is crucial to the role of the Central Bank and the Department of Finance in assessing, communicating and responding to such risks. A key role is also played by non-state actors in providing review, analysis, forecasts and challenge in the area of risk. This includes international bodies such as the European Commission, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the ratings agencies and the relevant domestic non-government body, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI).

We examined the extent to which the domestic institutions, namely the Central Bank and the Department of Finance, relied or purported to rely on such analysis in their own assessment of the risks.

In the years leading up to the crisis, multiple warning signals were given by domestic and foreign experts and economic institutes.1 These warnings highlighted concerns in respect of:

Not all warnings were robust enough and were mixed with positive comments and praise for the Irish economy. Most of these warnings were however, either discounted or ignored by both the Irish regulatory and governmental authorities and decision-makers until it was too late to avert the crisis.2

The evidence provided by a number of witnesses relating to this period confirmed that a high degree of reliance was placed by Government and state institutions on the reports of international organisations and economic committees regarding the Irish economy. They appeared to take comfort from these reports as they viewed them as independent.

Speaking about the impact of the views expressed by International institutions such as the European Commission, IMF, OECD and ratings agencies, former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, said:

“These organisations have the advantage of having international perspectives, and the insights they provide are especially valuable when considering economic conditions and prospects in a comparative context.”3

Former Governor of the Central Bank, John Hurley also said: “Given their cross-country perspectives and their experience of crises, the Central Bank regarded the views of the OECD and the IMF as very important.”4

Between 1994 and 2000, the average national house price increased by more than 150%.5 Between 1998 and 2000, a broad consensus had emerged that these increases were justified by the stronger domestic economy and lower interest rates resulting from the forthcoming entry to the Euro.6

In 2000 and 2001, concerns were evident that the international economic cooling after the bursting of the so-called ‘dotcom-bubble’ and other events would also negatively impact on Ireland’s economy.7 Although a slowdown in the Irish economy was noticeable, it did not last long, as the stronger domestic demand soon led to re-acceleration of GDP and house price growth.

Following the relatively short slowdown in 2001 – 2002, the economy resumed its upward momentum, with strong growth continuing from 2003 to 2007.

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, former Research Professor at the ESRI, John FitzGerald, described the economic background for the pre-crisis period. He noted the rapid decrease in productivity growth in the early years of the 21st century and the ensuing loss of competitiveness, the growth in house prices, a rate of house completions not justified by population growth, the rising current account deficit, increased borrowings from abroad raising the vulnerability of the banking system and a rapid increase in household indebtedness.8

In considering the extent to which the state institutions heeded and responded to the signals from economic forecasting institutes and other commentators in the pre-crisis period, two key questions arise:

The European Commission is an independent supranational authority. It is separate from governments and acts as the executive body of the European Union (EU). The European Commission is responsible for proposing legislation, implementing decisions, upholding the EU treaties and managing the day-to-day business of the EU, including drawing up the budget of the EU. Economic regulation is one of the key areas in which the European Commission has extensive legislative powers.

It is important to note that the assessments of external economic forecasters like the European Commission/ECOFIN, IMF or OECD were, to a certain degree, based on data and information provided by the Irish authorities, including the Department of Finance and the Central Bank.9

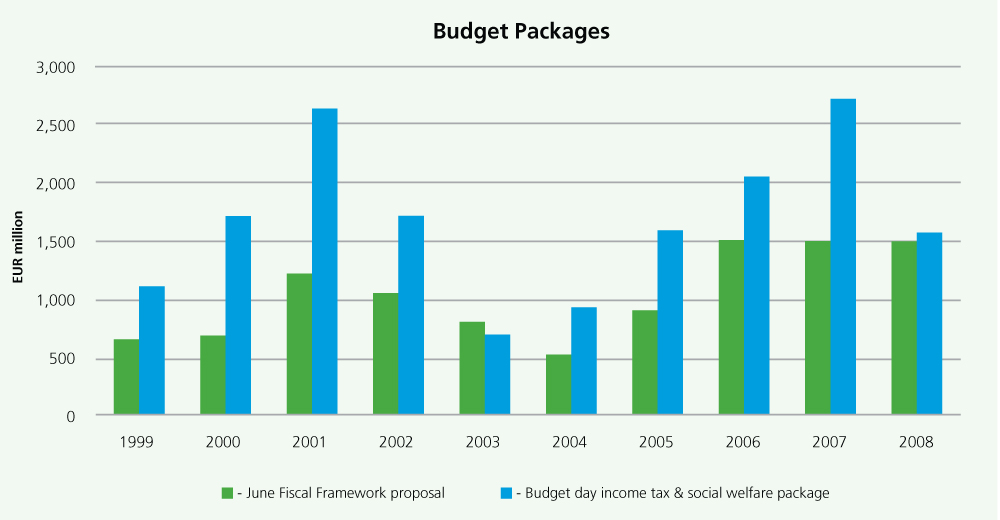

The first material warning from the European Commission was in 2001, when it recommended to the ECOFIN Council (known as ECOFIN) that there should be a censure to the Irish Government on the Irish economy. The Commission concluded in a published opinion by ECOFIN that the Irish Government’s planned 2001-2003 Stability Programme was not consistent with the European Council’s Broad Economic Policy Guidelines. While the Council acknowledged that Ireland had “fully and comfortably” fulfilled its obligations in relation to Debt to GDP, it nonetheless warned about the pro-cyclicality of planned cuts in indirect and direct taxes, describing them as “aggravating overheating and inflationary pressures.”10

ECOFIN also highlighted the threat posed by the Government’s expansionary fiscal policies:

“The Council recalls that it has repeatedly urged the Irish authorities…to ensure economic stability by means of fiscal policy. The Council regrets that this advice was not reflected in the budget for 2001, despite developments in the course of 2000 indicating an increasing extent of overheating. The Council considers that Irish fiscal policy in 2001 is not consistent with the broad guidelines of the economic policies as regards budgetary policy.”11

On a review of the minutes of the ECOFIN meeting of 6 November 2001, it is apparent that measures were taken to re-visit the recommendation of ECOFIN in light of the sudden cooling-off of the economy after “unexpected developments” (e.g. the slowdown in the US, the foot and mouth disease crisis and events of 11 September 2001). The minutes stated:

“…the inconsistency addressed in the Recommendation between the Irish budgetary plans and the goal of economic stability has lost part of its force for this year… However, the Commission argues that the experience of overheating in the Irish economy justifies continued vigilance regarding the evolution of the fiscal stance.”12

In his evidence, Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs with the European Commission, confirmed that “the assessment no longer raised any major issues.”13

In their supervisory role, general commentary from the European Commission and IMF contained critical remarks in relation to pro-cyclical fiscal policies of the Irish Government during this period. However, there was no specific warning on the development of a potentially large fiscal structural deficit.14

Marco Buti said that “…the Commission regularly stressed the uncertainty surrounding estimates of the structural budget balance for the Irish economy” . He also mentioned that there was “the sense that the structural fiscal position was weaker than the official estimate suggested, but there was no way to substantiate this view,”15 and he confirmed that the European Commission was of the opinion that the Government’s targets for the budget balance were not regarded as “particularly ambitious” in view of the strong economy.16

Marco Buti explained that the European Commission recognised that the Irish Government relied increasingly on income from property taxes and housing taxes, but given that the country was in surplus, it was “very difficult to say it was not behaving according to the Stability and Growth Pact, because it did.”17 Marco Buti admitted that the European Commission did not signal the risks in a sufficiently strong way.

The models employed by economists in the European Commission and the IMF did not give an early or good indication of the structural deficit in the years before the crisis. However, this was only identified after the crisis. It was explained that the available tools to measure a structural deficit were harmonised for all EU member states, which impacted in different ways on larger and smaller countries/economies, making it more difficult to assess compliance. In addition the model methodologies assumed that high output levels of the Irish economy and the related booms in tax revenues were permanent structural features.18 In hindsight, this assumption was proven to be wrong.

There was an over reliance on Ireland’s compliance with the limits set out in the Stability and Growth Pact. As Marco Buti said in his evidence to the Joint Committee:

“As the Government deficit remained below the Maastricht limit of 3% of GDP, the post-2001 Council opinions did not identify any formal conflict with existing EU fiscal rules.”19

While the economic models in use at a European level have improved since the crisis,20 doubts still remain in the Department of Finance as to the effectiveness of such modified models, in a small open economic setting such as Ireland. John McCarthy, Chief Economist of the Department of Finance confirmed that the methodology being applied even today is: “… a methodology that is designed to fit France and Germany. Unfortunately, it is a one-size-fits-all approach. It does not work for Ireland and I can say that quite definitely”.

He confirmed that there “have been some minor improvements to the methodology but they are not game changers”.21

Between 2001 and 2007, no specific assessment of the Irish banking sector was required under the European Commission’s Irish Stability Programme updates.22 The European Commission focused instead on the key ratios of the Stability and Growth Pact.23 As these requirements were mainly adhered to until 2007, no further in-depth studies that could have identified additional risks to the macroeconomic financial stability were carried out. The then Minister for Finance, Brian Cowen, stressed Ireland’s adherence to the Stability and Growth Pact in responding to questions about his tenure.24

The European Commission identified the risks of a sharp downturn of house prices and of a sudden end to the construction boom in its 2005 update of the Irish Stability Programme. However, this provided only limited understanding of the extent to which these risks presented a challenge to overall macroeconomic stability.25

A substantial part of the IMF’s work involves the monitoring of economic and financial developments and the provision of policy advice which is focused on crisis-prevention. In relation to this work and under its established Financial Stability Assessment Program (FSAP), the IMF also prepares regular Financial System Stability Assessments (FSSA) for most of the developing and emerging market countries.

During the pre-crisis years, the IMF provided and published annual Article IV consultation reports. These reports are generated from the bilateral discussions with member countries and cover the economic outlook and the Financial Regulators’ policies.26

The regulatory authorities in Ireland were aware of the considerable risk which the overheating construction sector posed to the economy. Bertie Ahern stated that besides others, the IMF had warned about the risk in 2004:

“In October 2004, the IMF alluded to a possible overheating in the housing market, even though, subsequently, they themselves, and other economic commentators, implied there was no bubble.”27

In 2006, in addition to its annual Article IV Consultation,28 a detailed Financial System Assessment Programme (FSAP) was also published, in which it was stated that Irish banking had capital buffers sufficient to cover losses arising from a 55% fall in house prices and a 10% default rate.29 The IMF statement said: “The authorities did not provide detailed supervisory data as requested by the FSAP team, so the FSAP team could not perform its own stress tests.”30 While certain macroeconomic scenarios for stress tests had been agreed between the CBFSAI and the FSAP team, the lack of detailed supervisory data had apparently not been sufficient reason for the IMF to query the stress test results.

Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director of the IMF, said that the IMF had pointed out several significant risks for Irish banks in its 2006 FSAP but he regarded it as a failure that the top line conclusion in the FSAP said:

“The outlook for the financial system is positive, with financial institutions having sufficient cushions to cover a range of shocks and fighting [sic] the diversification of wholesale funding as a source of strength.”31

Although routinely identifying the risks arising from house price inflation or strong credit growth, none of the FSAP reports gave a clear indication of the impending crisis.

With regard to these reports, Ajai Chopra noted that the IMF had previously acknowledged significant faults in its surveillance ahead of the crisis.32 The IMF statement to the Joint Committee also acknowledged the limitations of the Financial Stability Assessment Process, which “relies in part on the quality and detail of financial information provided by national authorities” . The IMF statement also noted that “until 2010, the FSAP was an entirely voluntary program and not an instrument of IMF surveillance.”33

The OECD is, inter alia , an economic research institute dedicated to support economic development by continued monitoring of events in member countries as well as outside the OECD area. Its research includes regular projections of short and medium-term economic developments. The OECD publishes regular outlooks, annual overviews and comparative statistics. Among them is the ‘OECD Economic Outlook’ , which assesses prospects for member and major non-member economies and ‘OECD Economic surveys’ , which provide individual national analyses and policy recommendations.

European Commission representatives participate alongside OECD members in discussions on the OECD’s work programme and are involved in the work of the entire OECD organisation and its different internal bodies.

Like the IMF, the OECD undertook a detailed country review process every year in the lead-up to the financial crisis. While the OECD identified property inflation and strong credit growth, it did not identify a major risk emanating from the Irish banking sector.34

As late as April 2008, the OECD Economic Survey of Ireland affirmed that the health of the banking sector remained robust, based on a range of indicators and the results of stress-testing exercises.35 The stress tests used were Central Bank tests but they did warn of limits to the tests, the impact of a commercial property downturn or liquidity risks.36 Highlighted in the OECD Economic Survey was the risk, in the event of a shock, that the performance of the property loans were correlated, which would result in a deterioration of the asset quality of many loans.

Of particular note is that a “soft landing” theory for the housing market was the expectation voiced by the OECD in its Economic Survey published in 2006: “A soft landing is the most likely scenario.”37 The OECD noted in its 2006 Working Paper on Ireland’s housing boom that: “If a soft landing is defined as something that is both mild and gradual, there has not been a single case out of the 49 boom-bust cycles.”38

The limitations of the external monitoring processes were also acknowledged by staff members of the Department of Finance. A former Assistant Principal with the Department of Finance, Robert Pye, said that “most of the analysis” produced by the IMF and OECD was based on information supplied upon request by the Department of Finance.39

According to the evidence of a number of witnesses, the OECD was not immune to domestic pressures. Tom O’Connell, the former Assistant Director General and Chief Economist at the Central Bank, described being instructed to contact the authors of an OECD report to request retraction of a potentially problematic examination of Irish property prices in around 2005.40

The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) is an Irish independent research institute. Its research focuses on Ireland's economic and social development to inform policy-making and societal understanding. It is involved in research programmes with government agencies and departments and commissions research projects and competitive research programmes.

The ESRI provided regular quarterly macroeconomic reviews to both the Central Bank and the Department of Finance. In October 1999, it commented that a continuation of a strong economy and lower interest rates would likely further drive housing demand, increasing the risk of a house price crash in the future.41

Other key risks identified in papers produced by the ESRI included house price inflation, necessity of fiscal policy adjustments, dependence on the construction sector, loss of competitiveness, wage inflation, rise of personal indebtedness, overheating of the economy and stimulatory fiscal policy which the ESRI felt to be unwise.42 John FitzGerald provided a summary to the Joint Committee of the assessment of such risks in previously published ESRI reports between 2001 and 2008.43

In the years before the crisis, the ESRI did not undertake analysis or assessment of the Irish banking sector, as it had insufficient expertise in this area. John FitzGerald noted that the ESRI had stopped carrying out research on the financial sector before 2000 and expressed his regret that the data on the balance sheet of the banking system was not examined by the ESRI. He described this as “a serious mistake.”44

In its medium term review 2005-2012 the ESRI did include the economic assessment of a housing shock, including the possibility of a major fall in house prices. It stressed that this was not a forecast per se and that the ESRI was not suggesting that such a serious shock was inevitable. While the ESRI review noted the possibility of a soft landing for the construction industry, it suggested that this was increasingly unlikely.45 In October 2006, the ESRI highlighted the dependency of the employment market on the construction sector and recommended a cut in Government investment in the housing sector.46

In summer 2007, the ESRI included an article by Professor of Economics, Morgan Kelly, on the likely fall of house prices in its Quarterly Economic Commentary.47

Surprisingly however, the ESRI Medium Term Review published in May 2008 did not foresee any major problems and described the fundamentals of the Irish economy as sound. Professor FitzGerald said that the “upbeat tone” of the May 2008 Medium Term Review was “wholly unwarranted… The review completely missed the possibility of a financial collapse” .48

Rating agencies assign credit ratings to debt issuers. The credit rating indicates the debtor’s ability to repay debt and is also indicative of a likeliness of default. It thereby determines creditworthiness and consequently has direct influence on borrowing costs of debt issuers and the preparedness of investors to lend to the rated institution.

During the 2003–2008 period, the credit rating agencies saw the Irish banks in a generally positive light. Ratings of the large Irish banks were among the highest in Europe. In addition to the banks’ strong profitability growth, ratings of the large banks were also supported by “assessment of a high probability of systemic support in the event of a stress situation”.49

In Part 2 of its Financial Stability Report 2006, the Central Bank includes the following quote from the Standard & Poor’s rating agency (S&P):

“The potential for nationwide banking crises and individual bank failures over the medium term appears lower in 2006 than at any point in the last decade. The past few years through to the present is looking more and more like a golden age in global banking”.50

While the share prices of all Irish banks had reached their highest valuations in either the first or second quarters of 2007, their subsequent fall over the following months was not immediately seen as a problem that was peculiar to the Irish banks, but rather as a reflection of general liquidity problems across banks internationally.51 This was also supported by the fact that the ratings of the Irish banks remained high until late 2008.52

On 1 January 2008, when property prices had been falling for almost a year and lack of liquidity in the interbank markets was already apparent, the Irish banks still enjoyed high long term credit ratings:

The rating agencies and equity market analysts in general were slow to recognise the impending financial crash. The principal agencies, Moody’s and S&P, reviewed the Irish banks in May/June 2008.53

Despite highlighting Anglo’s “apparently aggressive growth rates in recent years”54 , a “sizable degree of exposure to the commercial investment property market”55 and “the institution's wholesale funding reliance”56 , Moody’s maintained its A1 rating for Anglo in its 2008 Review, citing its “sound profitability” and “good credit quality supported by a rigorous lending approach” . Meanwhile, S&P maintained ratings for AIB and BOI at A+ and Anglo at A, while IL&P was lowered from A+ to A.57

The rating agencies’ “outlooks” on AIB, BOI and Anglo Irish Bank were adjusted for all three banks in June 2008 but they were not downgraded until November 2008, when the rating of Anglo was taken from A to A- by S&P.

The IL&P rating had been downgraded by S&P twice in 2008: from A+ to A in June, 2008 and from A to A- in November 2008.

In summary, therefore, it would appear that the rating agencies provided little indication of the problems which would befall the banks very shortly afterwards. This was also confirmed by Con Horan, former Prudential Director and Financial Regulator, who mentioned the rating affirmations around July 2008 and “a view at that time, I think, even from international rating agencies, that the Irish banks were able to ride out the problems at the time.”58

The Joint Committee heard that there was a high level of trust placed from external national and international economic forecasters, namely the IMF, OECD and ECOFIN/European Commission on correct data and other input from both the regulatory authorities (i.e. the Central Bank/Financial Regulator) and the Department of Finance. This input from the Irish regulatory authorities was an important factor for the production of their forecasts. Equally, national authorities and Government sources often quoted the views of the external forecasters as an important factor for their own economic views.

Michael McGrath, Assistant Secretary with the Department of Finance, described the level of engagement between the Department of Finance, the Central Bank and the ESRI as cooperative and business-like. He said that the Department had regard to the Central Bank’s independence and took very seriously the opportunity to comment on draft reports of the Central Bank and ESRI, supplying technical and policy-related comment for the institutions to consider. He noted that the Department took into account the reports of a range of bodies, such as the European Commission, the ECB, the IMF, the OECD and various international think-tanks, but that such external advice did not predict the crisis until it was too late.59

Derek Moran, then Assistant Secretary in the Department of Finance, stated that engagements with international bodies such as the European Commission, the IMF and the OECD were “challenging” and covered the full range of macro-economic and fiscal issues. He noted that external institutional commentators noted vulnerabilities in the public finances and suggested tighter fiscal policy but simultaneously praised Irish economic performance. He believed their views largely coincided with that of the Department of Finance.60 Derek Moran said that bodies such as the IMF warned of risks but “the narrative tended to soften” over time.61 He described the compilation of the OECD Country Reports as an inclusive process, during which the OECD would engage with the Department, the Central Bank, independent economists and journalists, taking “a very holistic view” before generating a report. The report was then made the subject of detailed examination by a large OECD committee.62

Tom Considine, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, in assessing fiscal policy during his tenure, noted the consensus view of economic commentators including the European Commission, the IMF and the OECD that the domestic and international outlook was broadly favourable.63

Notwithstanding the consensus view, it is notable that individual contrarian voices warned about strong credit growth and property price bubbles as early as 1998. Some commentators were sufficiently prominent to receive attention in the wider media area or in financial circles. Specific examples of these early warnings are articles by David McWilliams in January 199864 , William Slattery in February 200065 and Morgan Kelly in 2007.66

A review of the framework that the Central Bank and Financial Regulator operated in and the actions taken by these regulatory authorities over the relevant period, are critical in understanding the contribution of the regulatory authorities to the crisis.

The need for regulation stems primarily from the fact that most financial services businesses require customers to trust them with their money. This often involves long periods of time.67 Customer trust maintains confidence in financial institutions and stability in the financial system allows them to operate effectively. Regulation is used as a tool to create or enhance customer trust.

There is often an unequal relationship between banks and their customers in relation to information and expertise. Consumers therefore need to rely upon and trust banks and the Financial Regulator plays a key role here.

The principal elements of financial regulation may be categorised as:

Some other key terms relevant to financial regulation are:

Risks to financial stability include both systemic and non-systemic risks. These risks have become more complex with time, as financial institutions have grown larger and increasingly interdependent upon one another. In many countries, including Ireland, the banking sector was, and continues to be, dominated by a relatively small number of large institutions.

Increased reliance on wholesale funding (outlined in Chapter 1) also resulted in significant interdependency between financial institutions. The failure of any one bank may therefore have unforeseen knock-on effects, as other creditor banks are forced to absorb losses, thus creating a wider contagion risk.

Reference will be made throughout this report to the fact that Ireland adopted a “principles- based” approach to regulation. This contrasts with the “rules based” approach, which is used in some jurisdictions, most notably the United States. The difference between the two approaches can be compared to compliance with the spirit of the law (principles-based approach) or the letter of the law (rules-based approach).

The success or failure of either regulatory approach is dependent upon ensuring proper adherence to and enforcement of the principles or rules applicable to the approach adopted. An intrusive style of regulation can and should be a key part of both regimes.

Regarding the Irish regulatory system in the decade before the financial crisis, former CEO of IFSRA, Liam O’Reilly said:

“The approach of the Financial Regulator was that of a principles-based regime. Such a regime was also the standard approach throughout Europe and was in line with the Basel capital requirements. The approach was well known and enunciated by the Financial Regulator, and by Government, and publicly accepted.”74

Financial regulation both pre and post-crisis was subject to both European and domestic legislation. EU policy towards regulation in the years prior to the financial crisis was outlined by Marco Buti who made the following key points to the Joint Committee:

The European framework therefore provided a minimum set of requirements which had to be complied with across all Member States. Provided those minimum requirements were met, Member States were able to impose additional requirements according to their own needs.

Domestically, prior to 2003, banking regulation had been undertaken by the Central Bank of Ireland. Its two specific objectives were the protection of the banking and financial system as a whole and the protection of depositors and clients of banks and investment firms.

The Central Bank’s longstanding approach to regulation comprised of a process termed “moral suasion” ,77 described by Patrick Honohan, the Governor of the Central Bank as being:

“…. non-legally binding requests whereby one says, “Please stop doing this, please stop doing that” and if the banks know what is good for them, they say, “Okay, yes, let’s behave differently”. However, if they do not respond, it has to be followed up with enforcement, strict directives and rules.”78

The ability or otherwise of the Central Bank to enforce such requests was essential. Former CEO of the IFSRA, Patrick Neary, said that a key tenet of the approach is that it “essentially placed boards and management of banks at the centre of responsibility for the prudent conduct of business.”79

Although the Central Bank was responsible for banking regulation, other financial institutions were regulated by a number of different Government departments and agencies, including the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment, the Director of Consumer Affairs, the Registrar of Friendly Societies and the Pensions Board.80

During the 1990s there was an acknowledgement of the need to better regulate financial services to police both prudential and consumer protection. The existing legislative structures were considered disjointed, with unclear responsibilities and little offered by way of consumer protection.81 Many financial scandals, including the DIRT Inquiry and Ansbacher accounts scandal, further undermined public confidence in the financial sector and added impetus for reform.

A key milestone for reform arrived with the publication of a report by the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Finance and the Public Service in July 1998. The report recommended establishment of a new Single Regulatory Authority (SRA) to oversee financial regulation, enforcement, and consumer protection.82 This proposal would have removed responsibility for banking regulation from the Central Bank with the creation of an independent “greenfield” structure. The alternative was to consolidate all financial regulation and consumer protection matters within the Central Bank.

The Government established a working party under the Chair of Michael McDowell to examine and report on the various options for an SRA. Charlie McCreevy, the then Minister for Finance, presented and sponsored the changes in the Dáil and the Central Bank and Financial Services Authority of Ireland Act 2003 (CBFSAI Act 2003)83 was passed by the Oireachtas. The CBFSAI Act 2003, as passed, reflected the Government’s choice to proceed with a compromise approach to the restructure based on a minority recommendation made in the McDowell Report, crafted by Dermot McCarthy, then Assistant Secretary in the Department of the Taoiseach.84

The new structure comprised a separate Single Regulatory Authority (SRA), known as the Irish Financial Services Regulatory Authority (IFSRA), with its own board and which was to sit within a restructured organisation to be called the Central Bank and Financial Services Authority of Ireland (CBFSAI). Factors which influenced the Government’s compromise decision included:

By the time the new structure was agreed and implemented, the banking sector was in the middle of a period of rapid growth and change.87

The new structure created by the CBFSAI Act 2003 was relatively complex in nature, and comprised three decision-making bodies:88

Prior to the separation of duties arising from the CBFSAI Act 2003, both micro-prudential regulation of the banking sector and oversight of macro-prudential (financial stability) issues fell within the remit of the Central Bank. From 2003, the delegation of responsibilities for these areas was governed by a Memorandum of Understanding (the Memorandum) between the Central Bank and the Financial Regulator.90 The Memorandum sought to set out the division of responsibilities between the two entities and provided that the Central Bank would address overall financial stability, while the Financial Regulator would deal with the regulation of individual institutions. The Memorandum focused on monitoring but did not address the taking of actions. For example, it stated that the Central Bank’s role was to “…identify and advise… relevant parties”.91

Paragraph 4 of the Memorandum also clearly stated that the Central Bank was to be responsible for monitoring both micro-economic and macro-economic issues:

“the Governor and the Board's responsibilities therefore involve: ….analysis of the micro-prudential -where appropriate -as well as macro-prudential health of the financial sector.”92

The language used in the CBFSAI Act 2003 listed among the objectives of the Central Bank “contributing to the stability of the financial system.”93

The division of responsibilities within the Memorandum and the CBFSAI Act 2003 gave rise to concern expressed by some commentators and witnesses that lines of responsibility may have become blurred. The Honohan Report stated:

“The division of responsibilities between the Governor, the CBFSAI and IFSRA was novel and contained the hazard of ambiguous lines of responsibility especially in the event of a systemic crisis.”94

John Hurley also referred to the timing for implementation of the new structure: “the difficulty is that you separated at the wrong time the two functions and when you look back at it, the house was divided at a time when the bubble was inflating.”95

In explaining the role of the Central Bank in the lead up to the financial crisis, John Hurley said that, in line with the Memorandum, the Central Bank was responsible for providing “guidance” on financial stability and this guidance was given principally by way of its annual Financial Stability Reports. He said that confusion over the issue of financial stability may have been attributable to the power granted to the Central Bank to issue formal guidelines to the Financial Regulator under section 33D of the CBSFAI Act 2003.96 However, he said, such a situation never arose and that section 33D was not used, as the Financial Regulator had never disputed the findings of the Financial Stability Reports:97

“In hindsight, these assessments, as I have indicated, were not adequate. I fully accept the role of the Central Bank and my role as Governor in underestimating the risks to the Irish financial system.”98

Apart from the division of responsibilities relating to financial stability, the Joint Committee heard evidence of concerns relating to the division of duties between the Central Bank and IFSRA. Concerns with the legislation included the following:

a) The CEOs of the Financial Regulator (Liam O’Reilly/Patrick Neary) had to consult with the Governor of the Central Bank (John Hurley) on matters relating to financial stability and could only act with the Governor of the Central Bank’s agreement. For example, John Hurley approved the changes in capital ratios in December 2006, this additional requirement appeared to have an impact on decisions to take action.99

b) The Governor was not a member of the IFSRA Board even though, under the Memorandum of Understanding between the CBFSAI and IFSRA, the Governor and Board of the Central Bank had a responsibility for overview of the domestic financial system as a whole.100

c) The IFSRA board included its Consumer Director but did not include its Head of Prudential Regulation.101 This supports the view of a number of the Inquiry witnesses that consumer matters were given more attention than prudential matters.102

d) Former Chairman of the IFSRA Board, Brian Patterson said that the ability of IFSRA to act on its own accord was also limited in a number of other ways:

“[IFSRA] had a degree of independence but operated within the overall framework of the Central Bank…..The regulator inherited most of its staff from the Central Bank and so also inherited, and was effectively constrained by, the Central Bank’s HR policies, systems, and culture…which, in my view, was generally hierarchical, deferential, cautious and secretive….this did slow down our banking regulators from coping with change, of which there was a lot during the period, and in developing their crucial data analytics capability.”103

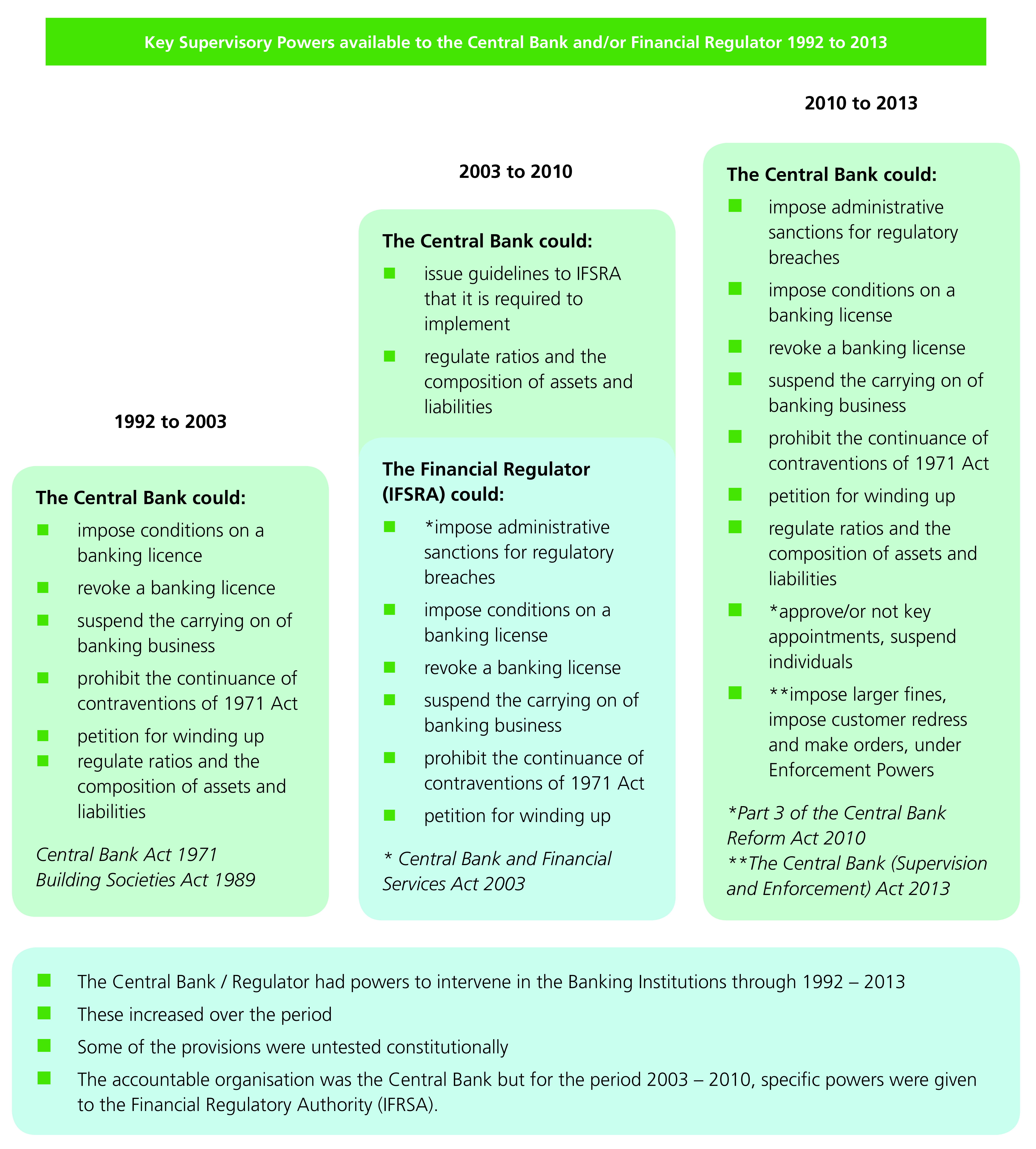

Illustrated below are the key supervisory powers that were available to the Central Bank and Financial Regulator.104

A range of opinions were voiced by the witnesses to the Inquiry as to the availability and use of powers by the Central Bank and the Financial Regulator.

A number of banking witnesses described prudential regulation as “light touch” . Michael Fingleton, former Chief Executive of the INBS, noted that “harsh experience has taught us that light touch regulation can have enormous and disastrous market distortions” but suggested that, if the Financial Regulator had adopted a “more interventionist” approach, it would have been out of step with the international regulatory consensus.

Former Chairman of AIB, Dermot Gleeson, described the Financial Regulator as taking a “relatively hands off approach on prudential and competition matters” allowing the most aggressive lenders to prosper.106 Former CEO of Bank of Ireland, Brian Goggin, commenting on 100% mortgages, “saw no reason why the regulator wouldn’t intervene in an environment where the market was just getting out of hand” .107

In his evidence, Patrick Honohan confirmed that the Governor of the Central Bank had powers either directly or by issuing appropriate guidelines to the Financial Regulator to require banks to maintain specific ratios, issue guidelines on the policies and principles the Financial Regulator was required to implement, attach conditions to banking licences and issue requirements on liquidity buffers and sectoral limits. He did also note that, while these powers were available, the normal operation of the Central Bank did not at the time utilise the powers to instruct the Financial Regulator, which had its own specific powers available.108 When this was put to John Hurley, he stated his belief that the powers of the Governor of the Central Bank and the Central bank were “theoretical” and that the only power that he could have used was one of “guidance” . John Hurley was of the view that “the detailed powers were actually with the Financial Regulator” .109

Brian Patterson, the then Chairman of IFRSA, stated that the Financial Regulator could have attached conditions to licenses and “done more” in imposing capital requirements. He noted that the Financial Regulator could “in extremis” have sought emergency legislation from the Government.110 Patrick Neary accepted that “there were tools available to us” , and noted “if we had…considered them in the context of needing to do something, we would have found a way.”111

Liam Barron, former Director General of Central Bank and Director of CBFSAI, said that it was his understanding that the Financial Regulator had “sufficient statutory powers to discharge its regulatory functions.”112 Former Head of Banking Supervision in the Financial Regulator, Mary Burke (May 2006-October 2008), noted that “the regulatory powers available to IFSRA and the bank before it, were broadly sufficient, aside from those with respect to crisis management and resolution” . She stated that in the period 2003 to the end of 2008 “even where regulations were sanctionable under the administrative sanctions process….no prudential enforcement cases were pursued against credit institutions” . Regarding the question of whether the Financial Regulator had the power to halt the amount of lending by the banks to the property and construction sector, Mary Burke said:

“My view is we had a number of powers. We could have set ratios, we could have set requirements regarding the composition of assets and liabilities; we could have imposed conditions on bank licenses”.113

Frank Browne, former Head of Financial Stability Department of the Central Bank, stated:

“It is my belief that the FR had sufficient powers to take direct actions against the banks.”114

Adrian Byrne, former Head of the Banking Supervision Department of the Central Bank, suggested in his witness statement that the IFSRA Board “had sufficient powers to take direct action against banks in order to avoid a financial stability crisis.”115

Deirdre Purcell, non-executive Board member of IFSRA and of the Central Bank, stated in her witness statement that, when granted direct sanctioning powers “there was caution within the FR before acting…in order to cut off recourse to the courts.”116

Gerard Danaher, member of the board of the Central Bank from 1998 to 2010 and of the Financial Regulatory Authority from 2003 to 2010 commented:

“The Financial Regulator did not seek significant additional powers in relation to the banks and never fully availed of the powers it had.”

In his opinion, in the context of increases to capital ratio requirements and the imposition of heavier capital weights on certain mortgages, it was “not a lack of power…but excessive caution which…led to the steps in question being too little and too late.”117

The boards of the CBFSAI and IFSRA and their members formed part of the regulatory and Supervisory regime. It appears, however, that there was an absence of relevant experience on the part of members of both Central Bank and IFSRA in the years preceding the crisis. Appointees to the boards did not seem to require regulatory experience and this was highlighted by Brian Patterson with regard to the selection of the IFSRA board:

“I tried to make the point that the board needed to have regulatory experience. There were people with banking experience on it.”118

Members of the Central Bank board also had a range of business backgrounds and experience but did not necessarily hold regulatory or banking experience. Former Non-Executive Director of CBFSAI and Central Bank board member, David Begg, highlighted the absence of specific training for the Central Bank board, once appointed: “….. I don’t think anybody received any training. I’m not aware of anybody else who did, at least.”119

Former Chairman of the IFSRA Board, Jim Farrell, in his witness statement responded to questions of the knowledge and skill set of the board and their ability to challenge as follows:

“While board members seemed to have a clear understanding of the issues, there was much reliance placed on the economists to deal with the many technical and interrelated economic issues. In hindsight, having an economist(s) on the board to argue the finer points might have made a difference. Having said that, there were not many economists outside the Central Bank giving contrarian views.”120

In response to the same question Gerard Danaher said:

“As for the members of the Board and the Authority, they came from many different backgrounds. Some had a greater knowledge of the technical aspects of banking and economics than others. They seemed to me to have sufficient knowledge and expertise to be able to draw their own conclusions on financial stability aspects. I believe the reason why incorrect conclusions were drawn arose more from an overreliance on external and internal assurances regarding financial stability rather than any inherent lack of knowledge or expertise. In that regard, I do not believe that there was any particular correlation between the degree of professional knowledge of banking or economics and the level of perspicacity demonstrated by members.”121

The failure to act may be further attributed to the fact that warnings, in the early stages of the boom, were ignored. When the economy continued to grow strongly, there was a tendency to ignore warnings contained in the Financial Stability Reports and elsewhere.

Whilst there was much debate amongst regulatory policy-makers and academics about the design aspect of the CBFSAI, no review of the quality of supervision policy, practice or execution of CBFSAI appears to have been carried out by either the Department of Finance or the Minister for Finance. This was something that was highlighted by a number of the witnesses during the Inquiry hearings. While it must be noted that there is no statutory legal role for either the Minister for Finance or the Department in this regard, such a review after the introduction of the CBFSAI could have uncovered its structural shortcomings.

A review of the CBFSAI structure was undertaken by the OECD and IMF against Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision. According to Patrick Neary, “the conclusions of all these assessments by these independent expert bodies in relation to the Authority were very favourable”122 This evidence, again, highlights the reliance placed by the regulatory authorities on international organisations.

Despite the degree of change and reliance placed on the work of the Central Bank and Financial Regulator, the Department of Finance or Minister for Finance never carried out a review of the performance, effectiveness or impact once the CBFSAI was implemented. In this regard, a number of witnesses said the following:

Richard Bruton, Minister for Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation said:

“…I think the biggest objection I had was that we hadn’t stress tested the actual powers, the capabilities, the method of overseeing the financial institutions.”123

Brian Cowen commented: “I mean there was a review, I understand from Mr. Considine who was the Secretary General, where I think either the OECD and IMF did a peer review study of how this CB and IFSRA was working, sort of, came out okay…It just tells you that the Government’s mechanisms that were in place seemed to be working well” .124

We asked Charlie McCreevy about appointments to the boards of the Central Bank and IFSRA. When asked about the backgrounds of the State appointees, Charlie McCreevy defended the appointments made during his tenure as Minister as follows:

“…in setting up the new structure, you can look at all of the Dáil debates and all of the Seanad debates and all of the commentary and you’ll see all this concentration on consumer issues to the exclusion of nearly everything else….

“most of those people that I appointed, we did it in a small process. We put forward a few names, we put a journalist on that … to really give an emphasis on, say, really talking about consumer, so that other people had been, in all walks of life, had different experiences. And when you’re appointing a board, you appoint people to a board that you think bring different experiences to the area…..

“I don’t know what people were around…with regulatory experience that we would’ve picked from but, in any event … the board of a central bank, you’ll need a broad range of experiences….”125

The former board members who provided witness statements to the Inquiry gave their views on the skills, experience and political composition of the Central Bank and IFSRA boards. The response of one former non-executive director of the Central Bank and IFSRA, Deirdre Purcell, provides an interesting insight in this regard:

“I was surprised when I got the phone call from the appointing Minister asking me to join the new Board and I responded by telling him I had no academic or professional qualifications in banking…..He explained the consumer protection function of the Financial Regulator and said he envisaged my role on its Board to be that of the ‘ordinary‘ citizen who would aim to represent the ‘ordinary‘ customer of financial institution …. as for the ‘political composition of the Central Bank Board‘ …in truth, matters having been discussed around the table, I did not detect political bias in any decision of the Board.”126

Gerard Danaher said that he believed that his appointment may well have been a consequence of his political background:

“In my own case, by profession I was a Senior Counsel. As such, I was in a position to contribute at the Board on such legal issues as arose. While I was not a specialist in banking law, I did have an interest in statutory interpretation which was useful……Obviously, when very technical aspects of economics or banking arose, I deferred to the experts. I assume that my political orientation …. was a factor in my being appointed.”127

The Joint Inquiry questioned why more emphasis was not placed on regulatory or banking capability in the appointment to key financial state boards and in the process for identifying candidates, but this matter remains unclear.

The preceding sections have outlined some of the weaknesses and limitations of the CBFSAI Act 2003. The Joint Committee reviewed the key work done and actions taken by the CBFSAI and IFSRA during the years leading up to the crisis and found that these actions and inactions had a critical impact on the financial crisis.

Key areas reviewed include:

The CBFSAI conducted a survey of mortgage lending practices in 2003.128 The survey indicated that mortgage lending had grown at very high rates. For instance, it showed that between 1999 and 2002, mortgage lending increased by 77% from €24.7 billion to €43.8 billion. Three institutions were found to have granted mortgages with loan to value (LTV) ratios of above 95% and 100% in certain circumstances. Problems were also identified regarding income verification procedures and procedures for calculation of repayment capacity, amongst others.

Although the majority of banks had amended their credit policies, there was a high average level of exceptions to stated lending policies of over 20%. The survey findings identified that the level of adherence to the guidance issued by the Central Bank on prudent lending practices was unacceptably low.

The survey report findings stated:

“A second possible element would be to move beyond moral suasion and take direct action in the form of imposing requirements on institutions. However, the FSR must be mindful that aggressive action taken to force prudent behaviour on mortgage lenders may restrict the growth in mortgage lending and create a shock to the system that could negatively impact on a fragile property market.”129

When questioned by the Joint Committee, Patrick Neary was asked to confirm whether “The banks could effectively breach the limits without fear of any consequence from the regulator” , Patrick Neary responded as follows:130

“The sectoral concentration…limit that we’re talking about…yes”

The report concluded with a detailed action plan and follow-up programme for dealing with the individual banks. The programme stated that all inspection findings were to be issued to the chairman of each of the credit institutions and had to be considered by the respective boards. Each board was to review the compliance policy monthly. Stress tests were to be carried out to assess the institutions’ resilience in the face of an economic shock.

CBFSAI board members and the Central Bank, as reflected in a discussion at the Financial Stability Co-ordination Committee in April 2004, remained concerned about the strong lending growth.131 The minutes of the meeting noted that board members had concern about “a degree of euphoria in the property lending markets and that the boards and management of banks are being myopic about the potential risks.“132 In the same meeting, results of a ‘stress test’ exercise with the banks were presented and “It was noted that the exercise suggested that the financial system could withstand the type of adverse shocks set out.”133

The 2003 CBFSAI survey, together with the minutes from the Financial Stability Coordination Committee referred to above, and subsequent correspondence from the Financial Regulator to the CEOs of large lending institutions134 all indicate that both Central Bank and Financial Regulator were aware of the relaxation of lending rules and practices across the banks as early as 2003.

In addition to its concerns across the general industry, the Joint Committee also obtained evidence which showed that the Financial Regulator highlighted concerns that it had relating to governance arrangements at INBS. Letters written by IFSRA135 and its predecessor, the Central Bank, to INBS in 2002, 2004136 , 2006137 and 2008138 , cited concerns relating inter alia to corporate governance, strength of management expertise and the changing risk profile at INBS. The 2002 letter referred to above, also referred to issues raised in 1999 and 2000 which had still not been fully addressed. This series of letters reflects that the Financial Regulator was unable to progress changes at INBS over a period of years, notwithstanding the concerns expressed and repeat correspondence. Witnesses outlined some reasons why more robust action was not taken against INBS; but the fact remains that the situation, which had given rise to the concerns, was allowed to continue.139

Weakness in governance structures, procedures and risk controls were also subject to an ongoing dialogue between the Financial Regulator and Anglo over several years.140

Ulster Bank (through First Active) was one of the first banks to make 100% mortgages widely available in Ireland.141 In his evidence to the Inquiry, Cormac McCarthy, former Group Chief Executive and Director of Ulster Bank said that there was dialogue between Ulster Bank and the Financial Regulator “about aspects of the product” but that “the Financial Regulator did not object”.142

Patrick Neary, the then Prudential Director, said that “…the then chief executive was quite emphatic that it was not the role of the regulator to be banning products; that it was in conflict with the … the view of the regulator, that a full choice should be given to people and that the emphasis should be on the way in which they were sold to people rather than banning the choice.”143

The evidence of Brian Goggin, former Group Chief Executive of BOI, was that BOI entered the 100% mortgage market only reluctantly “to protect our franchise” .144 He said that the Financial Regulator expressed concern about 100% mortgages during a meeting in 2006 and that the Financial Regulator’s reaction to their introduction was to propose the application of a higher capital weighting to the 100% mortgages, which Brian Goggin said he himself considered to be pointless.145 Brian Goggin said that he proposed that the Financial Regulator should ban the provision of mortgages greater than 90%, but their response was that it was not the Financial Regulator’s role to interfere in the market.146

Patrick Neary expressly contradicted Brian Goggin’s evidence and said that that the meeting had been held to inform him of higher risk weightings for high-LTV loans: “I certainly don’t recall any strong argument from Mr. Goggin to have … the product withdrawn.”147

Michael Buckley, former Group Chief Executive of AIB, said that the Financial Regulator had expressed “generalised concerns” to the bank concerning the mortgage market and the increase in LTV ratios.148 Liam O’Reilly stated that the Financial Regulator considered the issue of 100% mortgages in the context of consumer protection.149

Although IFSRA did not believe its role was to interfere in the markets, in July 2005 it issued a general warning concerning 100% mortgages. IFSRA recommended that the banks consider the repayment capacity of customers and the suitability of such products for first-time buyers.150

Con Horan, former Prudential Director said that he had become increasingly concerned about the direction of property-based lending from the end of 2004 or early 2005 but that a proposal made in mid-2005 to increase the bank’s capital requirements on high LTV mortgages was not accepted:

“My understanding was that senior management in the Financial Regulator and the Central Bank had considered the matter but did not believe the action was necessary. Macro-prudential analysis on mortgage growth suggested developments could be explained by economic fundamentals.”151

Liam O’Reilly stated that he, as the then Chief Executive of IFSRA, had brought the proposal to the attention of the director General of the Central Bank but it was not applied because “house prices were stabilising, interest rates were set to rise and property prices were stabilising. “152

However, Con Horan made a further attempt the following year to have the measure introduced, and this time was successful. In his evidence, Con Horan said that: “This was the first time in almost a decade of an exceptional property market that the regulatory intervention was instigated.”153 He noted that there were concerns within the CBFSAI, both that this intervention would jeopardise financial stability and that it was inconsistent with principles-based supervision. The Honohan Report noted that this “belated and relatively modest” action was only taken after “a prolonged and agonised debate. “154

In its “Licensing and Supervision Requirements and Standards for Credit Institutions” , the Central Bank had set out “requirements and standards which it uses to guide it in the assessment of applications for licences and in the supervision of the business carried on by credit institutions.”155

The requirements and standards are non-statutory, but the banks were required to comply with the Central Banks supervision requirements “at all times.”156 The most widely referenced requirements for the banks’ lending business were those relating to “large exposure limits” and ‘sectoral concentration limits’. The sectoral concentration limits were non-statutory guidance as contained in the Licensing and Supervision Requirements documents.

These regulatory limits were designed to limit risk by restricting the total lending or “exposure” of any bank to a client or group of connected clients which exceeds 10% of ‘Own Funds’. 157 The banks also had their own internal limits for large exposures to clients. The amounts of these internal limits were usually a function of the internal credit grading applied to the individual client, based on the bank’s assessment of the risk. Patrick Neary said that he did not believe that the large exposure limits were breached by any of the banks in the run up to the crisis. 158

Notwithstanding the statement that these prudential limits were not, in fact, breached during the period, the scale of loans to individual borrowers increased dramatically in the years preceding the crisis. Commenting on the large exposures to individual property debtors which were eventually transferred to NAMA, Brendan McDonagh, CEO of NAMA, remarked “when you looked at the top 29 debtors they had €34 billion of borrowings, so €34 billion of the €74 billion that came to NAMA was borrowed by 29 people.” 159

Although these large exposures did not breach regulatory limits, breaches of the sectoral concentration limits were identified, as described below.

Intended to limit risk in financial institutions, these limits prescribe the percentage of ‘Own Funds’ (equity) which each bank can lend to any single sector or connected sectors. The Joint Committee found that these limits were breached and appeared to have fallen into abeyance. 160 Evidence provided to the Joint Committee indicates that the sectoral lending limits were actually treated as guidelines by both the banks and the Financial Regulator. 161 In his evidence to the Inquiry, Patrick Neary said that the Financial Regulator understood the sectoral lending limits to be guidelines but he acknowledged that it was “very easy to game it” , by which we understand he meant that the guidelines were open to manipulation and were manipulated. 162

When questioned, Patrick Neary went on to acknowledge that it was correct to say that the banks were effectively able to breach the limits without fear of any consequence. 163 He accepted that IFSRA should have examined sectoral lending limits more carefully and should have considered whether there was an alternative way for the Financial Regulator to deal with the associated risk. 164 He said: “I think the sectoral concentration limit was allowed fall into abeyance too easily, and I accept that, and I regret that…” 165

Gerard Danaher and Liam O’Reilly also confirmed their view that the sectoral lending limits were only guidelines and that their importance had been reduced. Gerard Danaher suggested that their importance had been reduced during the late 1990s and Liam O’Reilly pointed to around 2004, due to the forthcoming implementation of Basel II. 166

The effect of Basel II implementation was also confirmed by Con Horan, who stated that the view within IFSRA was that sectoral concentration limits did not form part of the Basel Process. 167 He confirmed that, where banks exceeded their limits, a process of engagement occurred between the banks and IFSRA but that IFSRA adopted a non- interventionist approach: “The Banks must make their own adjudication on their sectoral concentrations. “ 168

Rather than focusing on sectoral concentration limits, the Financial Regulator placed more emphasis on capital measures as the method for controlling the banks. 169 However, both Liam O’Reilly and Brian Patterson said in their evidence that enforcement of capital limits was constrained by an awareness that increased capital charges for the Irish banks could leave them at a competitive disadvantage to the “passported” EU banks, over which the Central Bank had no control. 170

With regard to the monitoring of these limits and exposures, there appears to have been inconsistency in terms of the speed and nature of response from the Financial Regulator. Evidence from some banks to the Inquiry was that the Financial Regulator often appeared slow to respond to notifications from the banks or, where a response was received, no meaningful answers were provided.

In this regard, we received evidence in relation to a response received by Ulster Bank from the Financial Regulator in 2007 regarding a sectoral concentration 250% CAP limit notification made by the bank. This response expressed the view that the Financial Regulator was “not objecting. “ The notification letter was initially submitted by Ulster Bank on 26 February 2007, with a subsequent letter on 28 May 2007, while the less than definitive written response was not received from the Financial Regulator until June 2007. 171 Patrick Neary accepted there was “a lot of correspondence” on this particular issue. 172

As outlined above, breaches of sectoral limits were not enforced and this lack of enforcement enabled the banks to continue to increase the concentration of property-related loan exposures in their balance sheets. In the context of AIB’s non-compliance, this point was acknowledged by Dermot Gleeson, when he said: “Now let me say to you; we would have been very well off not to have exceeded that sectoral limit. It’s a great shame that we didn’t [comply]….” 173

The failure to take more vigorous action against the banks was also acknowledged by Jim Farrell, former Chairman of IFSRA, in his statement:

“Having identified the key risks in those institutions, there was no excuse for not insisting that management take more forceful action. All board members, including myself, have to take responsibility for not pursuing those issues more vigorously with the management of the Regulator.” 174

When we asked Richie Boucher, Group Chief Executive of Bank of Ireland, about delays in receiving a formal response from the regulatory authorities, he said: “They would be back to us today in a nanosecond. I don’t think that timescale was evident in that period” 175

Gerard Danaher stated, on the operation and implementation of the sectoral limits, that they: “…were effectively dropped by the Bank prior to the establishment of the Financial Regulator. Such limits were not applied to the IFSC banks” 176

Liam O’Reilly said, in respect of the non-enforcement that, in the years leading up to full implementation of Basel II in January 2008, less emphasis was being placed on sectoral limits. He also maintained that the limits were no more than guidelines. 177

“In 2004 I think it was, there was a move towards the Basel II limits and there seemed to be a crossover between which system should be used, but at no stage were there mandatory limits.” 178

A Speaking Note prepared for Charlie McCreevy for an Informal ECOFIN on 13 September 2003 stated the following:

“The concentration of risk exposures in the housing and commercial property markets merits close attention and is being monitored by on-site visits by the Supervisory Authorities to credit institutions.”179

Notwithstanding this early recognition of risk in the domestic construction sector by Charlie McCreevy, commercial property concentration levels and the associated risk only publicly emerged as a major concern for the Central Bank and Financial Regulator when they were identified as such in the 2007 Financial Stability Report.

In 2006, the CBFSAI board considered an internal report entitled “Is there a homogenous Irish Property Market?”180 The question addressed in the report was whether, based on historical experience of the property market, any fall in Irish property prices could be expected to occur across all segments of the market simultaneously.

Key conclusions were that:

On the question of publication of the report, it was agreed that it was important to convey the messages contained in the report to lending institutions. However, consideration was given as to how this should be done as the Central Bank wished to avoid provoking an “over-reaction” to the report’s findings. It was agreed therefore that the message should be communicated in the Financial Stability Report.181

The Interim Financial Stability Report published in the first quarter of 2007, entitled “Update on Risks and Vulnerabilities” , noted three major vulnerabilities for financial stability but also noted a concern that credit growth rates to the commercial property sector remained high. The divergence between growth in capital and rental values was substantial and was noted as an emerging vulnerability. The report noted that:

“While the overall health of the banking system is robust when measured by the asset quality, solvency and liquidity of the Irish banks, the concerns identified in the Financial Stability Report 2006 remain, namely:

The 2007 Interim Financial Stability Report included a paper entitled “A Financial Stability Analysis of the Commercial property sector” which was aimed at investigating “…empirically the recent performance of the Irish commercial property sector, to better inform the risk assessment relating to the large increase in capital values and decline in yields.”183

In late 2007, within IFSRA, the Banking Supervision teams completed an inspection in five different banks within a ten day period. The focus of the inspections was on ‘the ongoing credit management of a sample of Commercial property exposures’ from the top 20 exposures of the respective banks reported to the Financial Regulator earlier that year.184

In the first quarter of 2008, letters were sent out to the five banks, with general findings that applied to all of them, and specific findings for each of the banks. The general findings included recognition that banks relied on confirmation from legal firms that security for loans was perfected. Given gaps in information on the overall indebtedness of borrowers i.e. details of loans with banks or other lenders, banks were asked to satisfy themselves that there could be no other claims on the same security.

The Financial Regulator also invited views on the perception of the banks that “a slowdown in residential development will not unduly affect large developers, as they have the financial capacity to postpone developments until the markets improved. “185

In an assessment of financial market developments on 8 February 2008, the CBFSAI reported concerns about defaults in the commercial property sector that might arise in loans with moratorium or bullet repayments, where no payments were made until developments were completed.186 Issues would arise if the value of the completed development turned out at less than the required repayment. The report also noted that the Irish banks were generally satisfied with the bigger property developers, though concerns were expressed over the ability of small developers to sell developments.187

In late summer 2007, the Financial Stability Committee of CBFSAI noted the first indications of potential liquidity stresses in Irish banking system after the disturbances in the international liquidity situation. By September 2007, Committee meeting minutes indicate that the Financial Regulator had instituted weekly liquidity reporting requirements for the banks.188

Liquidity turbulences were also discussed at the CBFSAI board meeting in the third quarter of 2007. At this meeting, the board noted that the Central Bank had confirmed with the Irish banks that the banks had no shortage of collateral eligible for the ECB tenders. Accordingly, there was no reason for the Central Bank to anticipate any requirement for emergency liquidity assistance.189

Mary Burke stated in her evidence that the IFSRA introduced new liquidity requirements from 1 July 2007 which involved quarterly reporting on liquidity. She said that there were concerns at the time that the Authority needed to be aware of what was happening in terms of bank liquidity. IFSRA moved to weekly reporting by late 2007 and in April 2008 the IFSRA felt that the monitoring of liquidity was “more urgent. “190

In January 2008, the four main audit firms were invited to a meeting with the Financial Regulator. In his evidence, KPMG Partner, Paul Dobey said:

“In 2008, we took steps to obtain assurances from the Financial Regulator… make sure they were aware of what the Financial Regulator was aware of. We spoke to the Central Bank because we wanted to understand ELA and the information … what dialogue was going on between the Central Bank and the euro system. And we did that in 2008 and we got the assurances we need from the deputy governor of the Central Bank of Ireland and we also spoke to the Department in relation to capital. Now, when we came along … and we, therefore, concluded that those banks were going concerns …“191

“We also had a responsibility to assess whether the going concern based on preparation of financial statements was appropriate… we had to go and make an assessment and get assurances from the system if I put it that way – the Department, the Regulator, the Central Bank, around the going concern based on preparation…” [It was the first time they engaged with so many other outside institutions] “…and it wasn’t done lightly … we had a dialogue with the regulator which was teeing up in November … it was unprecedented… we had a meeting with the Financial Regulator in early 2008 – it was meeting of the four firms with the regulator.”192

The evolution of liquidity monitoring and actions by the Financial Regulator is discussed in Chapter 6.

In 2005, IFSRA attempted to introduce new controls, including a Compliance Statement regime for Directors. However, Brian Patterson confirmed that the proposed implementation did not proceed due to a combination of intense lobbying from the financial sector, coupled with what he believed to be a lack of willingness by the Department of Finance to implement the changes:

“…in November 2004 the authority set out to use its discretionary powers under the Central Bank Acts to require compliance statements of directors in financial institutions. The consequential consultation process ran into a barrage of resistance from the industry…. Following extensive lobbying and discussion, the Department of Finance wrote to the authority in November 2006 asking it not to proceed with the necessary consultation process, “without first consulting the Department” – a clear signal to us that this did not have Government support.”193

The purpose and importance of the proposed regime was outlined in the statement of Con Horan:

“[The] proposal was to impose a formal condition on the licences of all credit institutions, thereby laying a strong foundation for the taking of enforcement actions under the administrative sanction regime that was being developed at that time. However, the proposal was not implemented as the belief was that the industry was overburdened with the changes brought about by the Financial Services Action Plan.”194

When questioned on the issue of Directors’ Compliance Statements, Brian Cowen accepted that he had written a letter to the Financial Regulator on the matter, but asserted the decision remained with the Financial Regulator: “We didn’t tell the regulator what to do in this situation.” Brian Cowen noted that the Financial Regulator had decided to defer proceeding with the proposal until consultation with the industry was complete. He also noted that the industry “were raising some issues about it” but said that “we weren’t involved in influencing the decision.”195

A Department of Finance Memorandum to the Minister, dated 11 April 2007, confirmed that the Financial Regulator decided to postpone implementation of the Directors’ Compliance Statements after “industry and other interested parties” raised “serious concerns” in response to an informal consultation. The Financial Regulator put forward instead that the proposed Compliance Statement provisions should be reviewed as part of a project for the consolidation and modernisation of financial services legislation and that no powers would be exercised in this regard pending the outcome of the review.196

IFSRA therefore did not proceed to introduce Directors’ Compliance Statements. From the evidence presented to the Joint Committee and as outlined above, this failure appears to have been due to general industry pressure. The situation was also referred to by Gerard Danaher, who made the following observation:

“As regards Corporate Governance Guidelines, this initiative also stalled and was ultimately ‘delayed’ pending developments at EU level. Again there was industry ‘blowback’ during the course of the consultative process. I do not recall Department of Finance involvement.”197

In the Joint Committee’s review of some of the actions taken by IFSRA in the years preceding the crisis, a number of areas have been identified where more forceful actions may have had some ameliorating impact on the size or scale of the eventual crisis. The failure to introduce the new legislative powers and controls described above appears to be one of those areas. Mary Burke, Brian Patterson and Gerard Danaher, provided their personal views of events surrounding the IFSRA’s withdrawal of Directors Compliance Statements.

In her witness statement, Mary Burke provided a summary of the overall approach and actions of IFSRA:

“… the issues were the strategic approach, and the willingness (or lack thereof), as well as the logistical wherewithal (or lack thereof), to use those powers to prescribe detailed rules/requirements, or to challenge and intervene in a manner which would impact banks’ business models. In the case of IFSRA and the [Central] Bank, this was I believe influenced by a number of external factors including the international approaches to regulation/supervision, government strategy/policy, promotion of Ireland as a financial services centre, industry influence on the shape of regulatory policy, costs, and, in the run-up to the crisis, an overoptimistic macro-economic view.”198

Gerard Danaher said:

“All in all, the Authority of which I was part should have much more forceful, should have ensured that these initiatives were seen through expeditiously and should not have been diverted or fobbed off by management reluctance, by drawn out consultative processes or by the promise of statutory review or pending EU developments.”199

In order to avoid similar failings in the future, Brian Patterson, offered the benefit of his experience to provide a suitable benchmark for future regulation:

“A modern Financial Regulator needs a board with regulatory experience and skills. It needs an enabling legal framework with strength to counter the naturally powerful influence of the banking sector. It needs to be well resourced, to have a fast-moving capacity to develop its IT capability and to recruit expert staff. It needs freedom of action and clarity in its legislative mandate that it’s single-mindedly to prioritise the stability of the banking sector over other competing public policy goals.”200

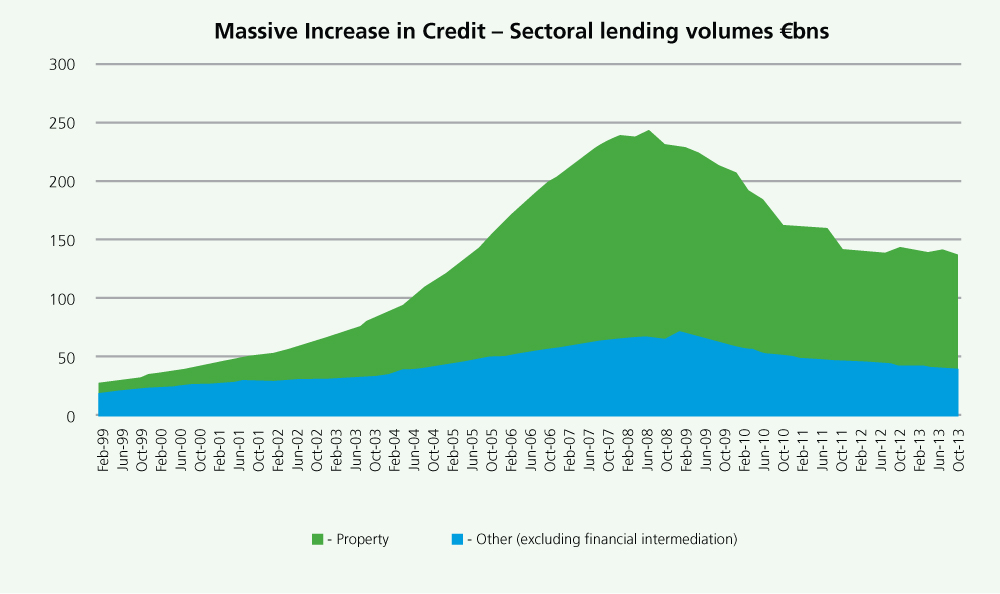

As documented in the Central Bank’s annual Financial Stability Reports, the regulatory authorities were aware of the explosive year-on-year growth in debt levels.201 In the build up to the financial crisis, the Central Bank or the Financial Regulator did not see sufficient specific threats to warrant more significant action to restrict or contain this growth. However, the Financial Regulator did introduce new capital requirements in 2006, but these measures were “too little too late.”202 This inaction can probably best be illustrated by reference to the growth in credit between 2000 and 2008.203

Source: Department of Finance204