Back to Chapter 4: State Institutions

In this chapter the Joint Committee will look at the critically important role of the Government. Together with the Department of Finance, Central Bank and Financial Regulator, it was believed to constitute the final line of defence against either an individual or systemic failure of financial institutions. Essentially, through policy actions, they had the ability to:

We will examine the factors that influenced the key decisions that the Government made in the period up to the crisis, the contribution of those decisions to the crisis, and the level of oversight which was applied to those decisions by the Oireachtas.

The Nyberg Report said the following in relation to responsibility for decision-making:

“People in a position to make decisions are and must be ultimately responsible for them regardless of what advice or suggestions they have received. The higher and more influential their position the greater their responsibility.”1

In his opening statement Brian Cowen, Minister for Finance at the time, used this quote from the Nyberg Report and said:

“In relation to the actions I took, I want to make it clear from the beginning that nothing I have to say here should be interpreted by anyone in any way as an attempt by me to pass the buck to anyone else.”2

He said:

“So regardless of what advice, you can’t, as an exercise of accountability, pass on that responsibility to anyone else, and I … as it says, the higher and more influential their position, the greater their responsibility. I’m prepared to live by that principle on these issues”3 .

He also said:

“…we made those policy decisions in the full knowledge of … and that was a decision for politicians to make, not, however eminent a civil servant might be, you know? So, we …we made policy decisions with our eyes wide open.”4

An underlying issue in the Government’s fiscal policy in the period up to 2008 was the development of an imbalance in the fiscal policy strategy.

A Structural Deficit develops when the amount of Exchequer expenses is higher than the amount of sustainable and stable income,5 where the source of finance for exchequer spending is over-reliant on temporary or transitional income components, for example property related Capital Gains Tax (CGT) or Stamp Duty. These types of taxes are sensitive, in that they will grow quickly in a boom but will reduce rapidly when there is a downturn in the economy.

In contrast, more stable revenue sources include income taxes which are less impacted by a downturn in activity. Taxation policy choices made by the Government contributed to a Structural Deficit developing, which was realised in 2008 when the tax revenue, particularly from temporary sources, reduced dramatically while the expenditure commitments largely remained or continued to increase. Consequently, the large Structural Deficit, which had built up over a number of years, was left exposed.

From 1994 onwards, Irish Exchequer revenue became increasingly dependent on property or construction related income.6 By 2006 - 2008, income from Stamp Duty and CGT collectively accounted for 15% of total revenues. A further 15% of revenues came from corporation taxes, which were strongly boosted by the activities of property development companies.7 These sources were only sustainable in the longer term if property related transactions continued at a similar level.8 However, this was not the case and when demand collapsed, so did the tax revenue that the Government relied upon to meet its commitments.

Tax Base Erosion was an important factor in the creation of the Structural Deficit. The Government made policy decisions which directly contributed to erosion of the Tax Base. These decisions are explored in more detail later in this Chapter.

The evidence given to us by former Taoisigh Bertie Ahern and Brian Cowen confirmed that the Government’s focus was on the requirements of the Stability and Growth Pact and on GDP/GNP related ratios like expenditure/GDP, Debt/GDP and Government balance.9 Bertie Ahern, Brian Cowen and Charlie McCreevy said that they had acted conservatively and balanced resources and demands responsibly during this period.10 In relation to his approach to the budget, Brian Cowen said:

“the IMF came over to this country and did an exercise, which took account of the buoyancy effects that you’re talking about in relation to the construction industry and came back and told us that there was a structural surplus - even when they took out the cyclical effect - that there was a structural surplus in the Irish economy of 2.8%.”11

John McCarthy, Chief Economist at the Department of Finance, said:

“The contraction of the tax base and the ramping up of public expenditure on a permanent basis were clear policy mistakes and ultimately led to a very large structural deficit once the crisis kicked in. That the public finances were in broad compliance with the requirements of the Stability and Growth Pact during most of this period provides no comfort.”12

In this section, we will look at some of the macro-economic factors that impacted on decision making.

Fiscal policy from 1998 until early 2008 was discussed with key witnesses during hearings before the Joint Committee covering key points such as:

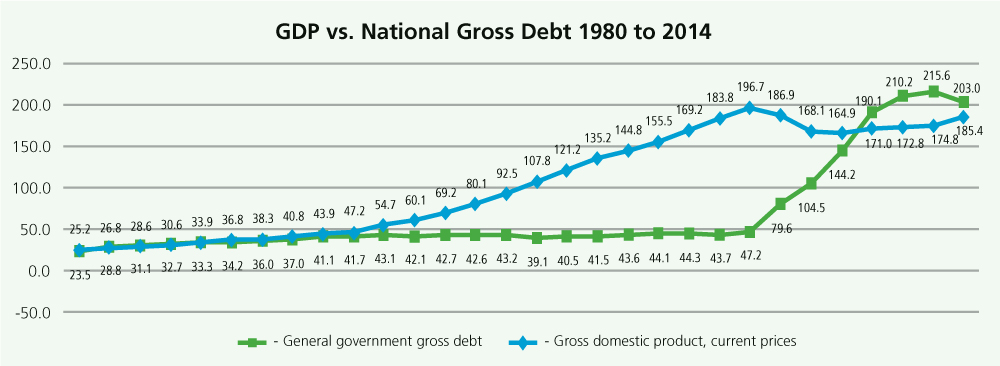

GDP is an important measure of economic performance. Governments have historically relied on a measurement of expenditure as a percentage of GDP as a basis to assess what was affordable. GDP growth in Ireland over this period was substantially stronger than in most other EU member states, rising from €53 billion to almost €197 billion, or by 272%.13 In contrast, growth of GDP over the same period was 27% in Germany, 131% in Spain and 129% in the UK.14

While the Debt/GDP ratio had improved dramatically, there was no reduction in the actual debt. Gross government debt remained almost unchanged at €44 billion during this period. It would appear that the strong revenues earned during the boom years were not generally used to reduce debt, but to increase expenditure. This suggested a priority on the short term rather than medium term management of fiscal risk.

This risk was realised when between 2007 and 2010, Ireland’s GDP fell by 19%, which caused a deterioration in the ratio, regardless of any additional debt taken on.

While the headline figures of total Government expenditure/GDP fell from 36.6% in 1997 to 33.3% of GDP in 2004, the actual amount of Government expenditure almost doubled from €26.7 billion to €51.8 billion in that period. By 2008, Government expenditure had tripled.15 The substantial rise in expenditure was obscured by the strong rise of GDP. However the affordability of this increase in expenditure was reliant on a continuing stream of non-cyclical taxes.

There were differences of opinion expressed by witnesses. Charlie McCreevy said: “No matter how these figures are interpreted, it is quite clear that there was no splurge over the period.”16 However, this was not a view shared by all. Bertie Ahern accepted that Current Expenditure was too high by 2007.17

Brian Cowen regretted that current spending growth was not lower in his time as Minister for Finance and said that he should have had a less expansionary approach to his Budget for 2008.18

Agreeing high levels of current expenditure created a further problem, Tom Considine said:

“From a sustainability viewpoint, gross voted current expenditure is particularly important because of the difficulty in reversing welfare, pension and pay increases once granted.”19

These requirements came into force in 1998. The aim of the SGP was to keep each Member State within prescribed limits on Government deficit (limited to 3% of GDP) and debt (limited to 60% of GDP). Since Government debt was generally well below the prescribed threshold throughout the relevant period, the budget deficit was afforded more attention.20

Every year from 1998 to 2007 (with the exception of 2002), Exchequer revenues surpassed official forecasts, mainly due to strong rises in property-related income.21 The 3% Government deficit limit under the SGP was generally easily achieved.22 The Government Budget showed a surplus in each year from 1998 to 2007, bar a small deficit of 0.3% of GDP in 2002.23

Once the Government had a balanced or even slightly positive budget, the tendency was then to spend excess income on budget day rather than using some of this excess to reduce debt.24

When asked why, in the years 1999-2002, the income tax and welfare package announced on Budget Day dramatically exceeded the recommendation made by his Department the previous June, Charlie McCreevy said “…because we were anticipating greater economic growth and greater economic growth was occurring.”25 This confidence in the ongoing growth funding the spending plans would prove to be incorrect.

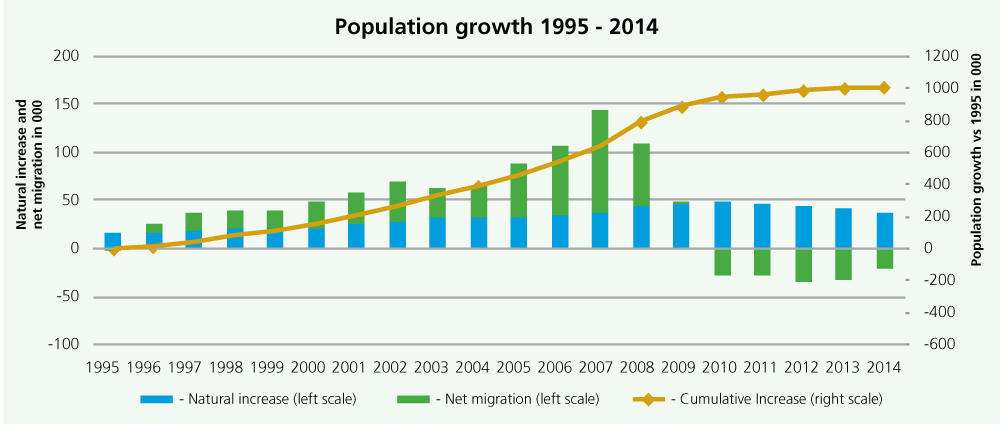

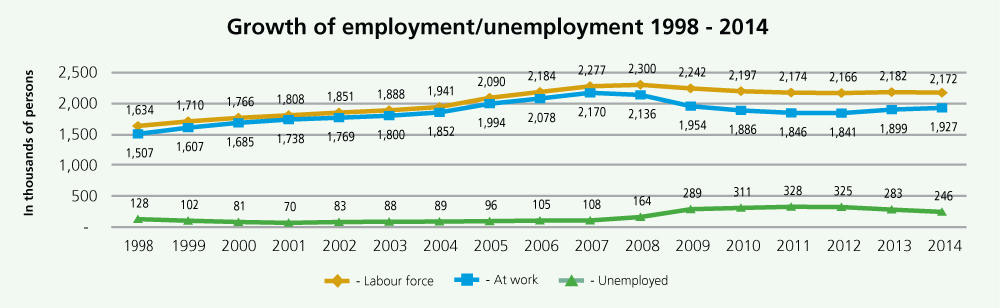

Ireland’s population grew from 3.6m in 1995 to 4.5m in 2008. Net immigration flows, along with a relatively young population, resulted in strong labour force growth, rising from 1.5m in 1998 to over 2.1m in 2008.26 Accordingly, the Government needed to provide housing, education, transport and public infrastructure, and services as well as safeguard living conditions for a rapidly growing population.27

Source: CSO28

Population and employment growth, combined with substantial income gains and headline inflation, substantially contributed to the rise in GDP and also led to a rise in spending.

Brian Cowen and Charlie McCreevy said that the increase in expenditure on social protection was a deliberate Government policy.29 Average social protection payments were increased significantly even though unemployment was below 5% for the first time in the history of the Irish State.

Brian Cowen spoke of having to make political and policy decisions when there was a budget surplus in order to address needs.30 Charlie McCreevy spoke of the moral and political pressure he felt to spend the money which became available. He said: “It is difficult to run a surplus in a democracy.”31

The need to house these workers added to demand in the property market. This further accelerated economic growth and resulted in increased property-related income and transactional tax revenues.

Source: CSO32

The commercial and residential construction sector expanded far beyond its historical trend line, generating a major increase in labour force supply and participation with one in every five persons working in the economy either directly or indirectly employed in construction. The primary and secondary effects of this expansion were significant.33

The Government’s finances were becoming increasingly dependent on, and vulnerable to, maintaining stability in this sector.

Residential and commercial development had depended on acquiring land for future projects. The higher Stamp Duty and CGT followed rising property price levels generated the expectation of further capital gains in the property/construction sector.

While house price inflation was a key theme of many economic commentaries and featured prominently in the Central Bank’s Financial Stability Reports, its impact on the Exchequer’s finances was largely positive in the years leading up to the crisis. The expectation that house prices would continue to rise, in turn, supported the demand for more housing, both for residential and investment properties.34

The substantial risk of a total collapse of construction activity and property activity was not contemplated.35 Bertie Ahern said:

“I believed that that was about 55,000 houses and I believed we could get back to 55,000 houses without doing too much. That was the sustainable level, so … and we were getting there and I thought, if we got there, then … we were okay.”36

The vulnerability of the commercial construction sector was illustrated by the PwC report on the banks in late 2008, which identified ‘land and development’ loans of €62bn.37 The true value of the lands which secured these loans was significantly dependent on the construction projects being completed and a significant dependency on rezoning being granted by local authorities.

As well as external factors which influenced Government decisions, there were discretionary decisions that the Government took which committed it to higher long-term expenditure. In this section, we will look at the role of Social Partnership and Programmes for Government.

Six Social Partnership Agreements were entered into from 1987 to 2005, covering three year periods, between:

From their inception in 1987 into the mid-1990s, Social Partnership Agreements assisted in delivering moderate wage developments and good industrial relations during times of substantial economic growth. These Agreements kept wage inflation in check over a prolonged period, thereby enhancing competitiveness and stimulating investment.38

From the late 1990s to 2007, the economy was operating at full capacity.39 Labour shortages and high wages demands followed and a loss of competitiveness became evident.40 As a result, the pay determination element of Social Partnership had by 2000, according to Dermot McCarthy become “an inflation-based bargaining process.”41

Early concerns on loss of competitiveness voiced by some commentators42 were outweighed by the strong growth of the domestic labour market. The construction sector accounted for a large part of the increase in employment numbers until early 2007.43

The benchmarking process for the public sector pay structures resulted from commitments made under the social partnership agreements. Benchmarking placed additional pressure on the Government as private sector wage growth had risen robustly. Once benchmarking had been carried out, it was agreed for a period of three years and so could not be easily reversed.44

The Programmes for Government in 1997, 2002 and 2007 set high-level goals for the Government in relation to spending and tax level commitments. Policies, such as the Government’s Decentralisation Programme, were introduced by Charlie McCreevy with little analysis.45 When questioned as to whether he believed that his announcement of decentralisation was a failure, Charlie McCreevy said:

“No, I don’t…..I see many great offices all over the country with decentralised civil servants from Dublin there and they’re doing very well and people … it’s rejuvenated some areas, people are very happy. I think the … the system and efficiency hasn’t deteriorated at all. I’m very … I’d be very sad that the total decentralisation wasn’t completed as we, as we had envisaged.”46

In examining the spending decisions, Rob Wright, former Canadian Deputy Minister of Finance, referred to findings he had made in the Wright Report, that the programmes for Government and Social Partnership Process helped overwhelm the Budget process.47

When this was put to Brian Cowen, he said “That’s their view.” He agreed that the Programmes were an influence, but he said it was the job of Government to implement the Programmes that it had brought in.48

A key responsibility of any Government is to produce an annual budget. As part of the process, a Budget Strategy Memorandum was prepared by the Economic Division of the Department of Finance each June or July. This was considered and reviewed by the Minister for Finance and brought to Cabinet with proposals where the spending levels were agreed.

However, by the time the Budget was introduced in the following December, the spending levels had invariably grown. Charlie McCreevy said that he viewed the June memorandum as “not so much as the Department’s advice…but as a starting point for negotiations”and he believed that the Department of Finance treated it the same way.49 When asked to comment on the process, Bertie Ahern noted “…that document is used as the opening discussion of a long process …”50

Brian Cowen said that the proposals from the Department of Finance would have been considered the “most conservative possible”and there would have to be “negotiations around that going forward.”He did accept that this was not best practice.51

Tom Considine was asked whether budgetary decisions were taken by the Government contrary to the advice of the Department of Finance, to which he replied:

“Not alone were they contrary to the advice of the Department but they were contrary to the advice of the Minister for Finance as well, as presented at mid-year when the strategy was set. So, as the year went on then … in the autumn, the pressures within the system meant that that advice was relaxed and the spending was greater for, as you saw there, for most years, apart from 2003.”52

When Charlie McCreevy was asked about advice, he responded:

“Democratically elected governments must, at all times, with their freedom, do what they consider best, in the interests of their people. Yes, this means the ignoring of some advice and the taking of others.”53

Tom Considine said that the Department “engaged”with the Minister to prepare a budgetary strategy memorandum submitted to cabinet in mid-year; the government decision was based on the memorandum and formed the basis of spending and taxation frameworks prepared for the next year. Other departments submitted spending proposals in autumn based on this decision.

The Department also prepared cost estimates for funding existing public services, used in pre-budget discussions with other departments. Reductions in funding below existing service levels in the 2003 and 2004 budgets were opposed by other departments, leading to pressures to increase spending in 2005, when the targets in the budget strategy memorandum were exceeded by €1 billion. He described a memorandum prepared in 2005 recommending targeted increases in expenditure for the 2006 budget. These targets were exceeded by a significant margin.54

When questioned about these spending pressures and asked why they could not have been resisted in the established budget process, he said: “it wasn’t for civil servants to make those decisions”55 , which were made by the Minister and ultimately approved by Government.

Asked whether the post-2003 budgets were decided “contrary to the advice of the Department”, Tom Considine stated that “the Department set out its stall”and the “advice was signed off by the Minister”but “it wasn’t possible to hold that line.” He stated that “the political pressure to spend”was too great.56

David Doyle, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, stated that general advice to government was set out in the budgetary strategy memoranda but accepted that fiscal policy as decided by Government was generally pro-cyclical in this period with expenditure increases and tax concessions adding to demand in the economy. He commented that prior to 2008, Budget Day packages in general ended up significantly higher than those recommended by the Department “as a result of the pressures exerted by the social partners, individual Ministers and the Cabinet.”57

Derek Moran listed a range of warnings included in the Budgetary Strategy Memoranda in relation to inflation, wage pressures, public spending, an overheating economy and increasing house prices and construction costs, noting that the Department had consistently advocated a tighter fiscal policy. He said that the Budgetary Strategy Memoranda “became an opening for policy discussion rather than a fixed fiscal framework, a floor rather than a ceiling.”58

Donal McNally said it was:

“a matter for political decision what the level of public spending should be and what the tax to fund that should be…as a civil servant, you do what the Government decides.”

Questioned on how the Department responded to calls from the IMF, the OECD and ECOFIN for a tighter fiscal policy, he said that such recommendations were highlighted in the Memoranda but the decision was left to the Government.59

The Government’s consideration of the Department’s advice was further explored during public hearings. Tom Considine and William Beausang said that while the Department’s overall advice was respected, the credibility of the Department’s budgetary advice in the years from 1998 to 2008 was weakened by the consistent occurrence of better-than-forecasted economic developments.60 Charlie McCreevy said that the provision of consistently conservative advice by the Department led to the Government often ignoring it.61

Brian Cowen’s view was:

“And the question of the Department of Finance advice is obviously you take advices from everywhere, you take … and you’d obviously take it from your Department. But at the end of the day, Government makes decisions, ultimately, based on not just technocratic advice but where they see identified need.”62

The budgetary process culminated in the annual announcements of fiscal measures on Budget Day. Professor Niamh Hardiman, UCD, had given evidence to the Joint Committee on corporate governance. However, she also said: “Irish Ministers for Finance have a tremendous amount of discretion when it comes to devising and implementing fiscal policy.”63

Charlie McCreevy outlined how Budget Day announcements included measures that were introduced by the Minister for Finance which were not previously known to or discussed with the Cabinet or with the Department of Finance.64 An example of those types of measures which avoided the scrutiny of the Department of Finance was decentralisation65 .

“When I was Minister, I made the final decisions on certain matters. You’d obviously do the courtesy of speaking with the Tánaiste and the Taoiseach beforehand and then on the morning of the budget you would outline what your full budget was to your Cabinet colleagues.”66

Charlie McCreevy, Brian Cowen and Bertie Ahern spoke about the impact of an upcoming election year on the Budget. Both Charlie McCreevy and Brian Cowen said that elections were an influencing factor on Government spending. They also accepted that Government decisions were made in pre-election years which led to increased spending.67 Charlie McCreevy said:

“…the upcoming election has always influenced measures which the Government do at election time. We are politicians, don’t forget, and we actually like to be re-elected.”68

When Bertie Ahern was questioned on the impact of impending elections on budgetary decision making, he said that he didn’t think that he had done anything irresponsible and “…to be honest with you, I hadn’t much competition in 2002[election].”69 When Charlie McCreevy was asked whether this was “a responsible way to run the national finances”, he said that the governments in which he served “reduced the national debt and still had budget surpluses.”70 This perspective was not shared by all witnesses.

David Doyle described political pressures for increased spending prior to the 2007 election when the Department was concerned that the construction industry was contracting and arguing for “a much lighter approach” but it never envisaged a depression.71

Derek Moran noted that the Department’s Stability Programme Updates had identified the risks stemming from the economy’s over-reliance on the property sector in 2005-2007. He believed that the Department did give appropriate advice on pro-cyclical policy, but accepted the criticism of the Wright Report that advice was given orally to the Minister without a record being kept. He stated that the failure to run tighter budgetary policies had “profound” consequences for the public finances; the adoption of such policies in the middle of the last decade would have significantly reduced the need for expenditure cuts and tax increases during the crisis resolution period.72

Permanent expenditure increases were being based on the “windfall” that came each November from transactional taxes. Derek Moran said that the Department was highlighting these risks sufficiently “at a macro-level”but not at the “micro level of tax head.”73

John FitzGerald commented on the fiscal policy, deeming it “most unwise”and he said that it “fuelled the problem … if we had a sensible fiscal policy, we would not be where we are now.”74

When questioned as to whether the reason for the difference in Budget forecasts from the Department of Finance recommendation to what was agreed by Cabinet in 2007 was because it was an election year, Bertie Ahern said; “I’m not going to deny it, but I don’t think that it was a huge part of the budget.”75

Brian Cowen was questioned on the role played by pre-budget submissions, follow-up meetings with industry organisations and the imminent budget in the approach to the 2007 budget. He could not say that it was never a consideration but said “…By the same token I believe what we did was responsible and was required and warranted.”76

There were a number of considerations that should have been considered in setting fiscal policy through the budget process, including ongoing affordability and medium term management of the state debt and spending commitments.

From the mid-1990s to 2007, Ireland experienced substantial GDP growth.77 At the same time, Government gross debt78 was maintained at a low level and reduced to less than 25% of GDP in 2006 and 2007. Ireland’s fiscal state appeared robust and healthy.79

The financial crisis highlighted the underlying structural deficit in a reversal of fortunes in the period from 2008 to 2012. For example, from 2008 to 2011, GDP fell by over 15%, while Government debt increased to in excess of 120% of GDP in 2012.80

Source: Eurostat81

Ireland’s headline positive financial status, which had been incrementally secured over the previous 25 years, deteriorated between 2008 and 2012. Significant austerity measures and a determined bank asset sale programme were implemented in order to prevent an even greater deterioration in financial conditions.

Ireland is now a severely indebted State, exhibiting one of the highest Debt/GDP ratios in the EU. A number of factors contributed to the sudden and dramatic downturn in Ireland’s financial status, two of which are:

Approximately €92 billion of new Government borrowing over the years 2008 to 2014 resulted from tax shortfalls due to the Structural Deficit81 - considerably more than the amount of approximately € 64 billion82 borrowed for bank rescue operations.

The General Government Debt as at 30 November 2015 stood at just over €201 billion.83

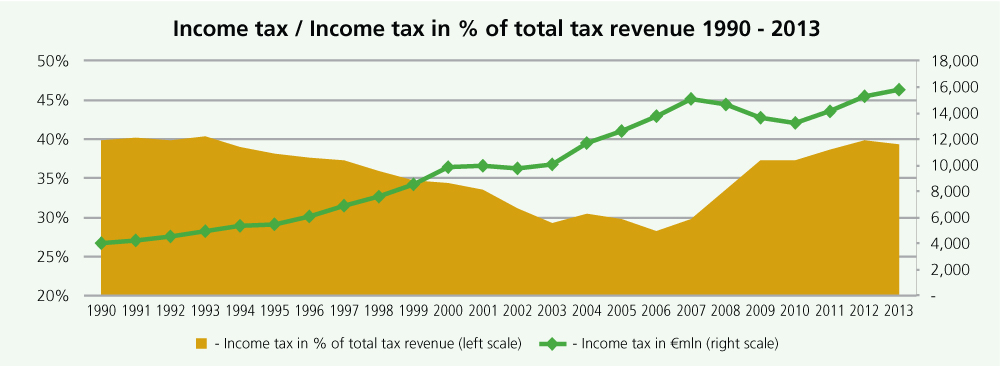

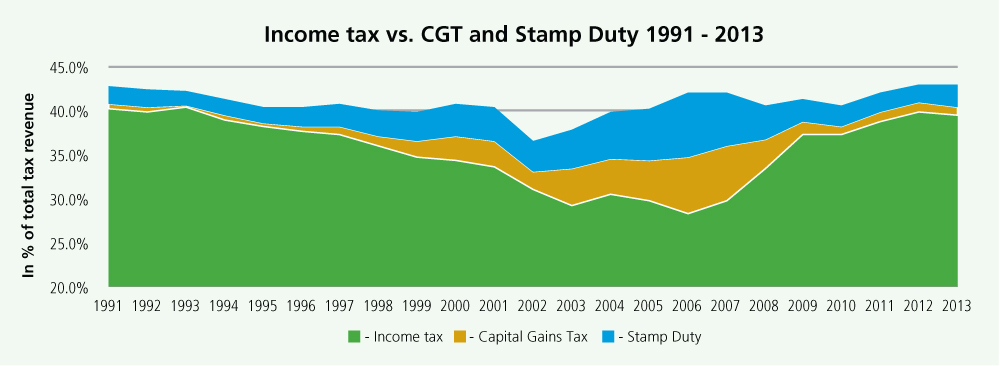

Choices made by Government in deciding on the taxation policy required for their expenditure plans in both current and future years, and on the impact of those choices. A Structural Deficit gradually developed over the years leading up to the crisis. The steady increase in revenues from Capital Gains Tax (CGT) and Stamp Duty enabled reductions to be made to previously stable tax revenue segments, most notably Income Tax.84 This meant that some traditionally robust and stable revenue sources were incrementally replaced by more cyclical and volatile tax intakes.85

The erosion of the tax base during the period from the mid-1990s to 2008 will be examined in the following contexts:

The rationale behind the change in tax policy, introduced by the Government, was outlined by Brian Cowen who said: “But the reason why, by the way, we had this move to, to capital taxes…because it takes down the burden on direct tax, on working people.”86

The strong and sustained increases in the overall tax-take over the ten year period from the mid-1990s onwards facilitated Income Tax rate reductions and a considerable widening of personal tax bands.87

Between 1997 and 2001, the Government decided to reduce the standard rate of personal Income Tax from 26% to 20%, while the higher rate was reduced from 48% to 42%.

In 1994, the share of Income Tax as a proportion of total tax revenues was 39%. This reduced to below 30% over the period 2002 to 2007.88

Against this background, Social Partnership agreements had been trading wage moderation for cuts in Income Tax in order to bring about real net income gains.89 Sustainable tax revenues rely on consistent non-cyclical revenue streams, of which Income Tax is a critical factor. There is an increased risk on the exchequer purse when total revenue raised has a reducing reliance on non-cyclical taxes.

The graph below shows the very strong growth in the nominal value of total Income Tax from the late 1990s onwards almost masked its declining contribution to the total tax take.

Source: Tax base erosion Ireland based on OECD stats90

Total Income Tax revenue continued to climb strongly until 2007. This was a consequence of expanding employment and rising incomes.

The large cuts in Income Taxes were considered affordable by the Government due to the considerable increases from other sources, notably Stamp Duty, CGT and VAT, all of which are heavily transactional in nature.91 Charlie McCreevy was questioned about narrowing the tax base. He did not accept that reducing capital gains, transaction and income taxes was narrowing the tax base; he believed that he had “reduced an unfair burden.”92

Brian Cowen said: “…that ten of the eleven budgets were in surplus, even though I had minor deficits budgeted for…”. He went on to state that the IMF had confirmed that Ireland had a structural surplus in both 2005 and 2006.93

When questioned about the sustainability of relying on property related taxes, Brian Cowen said:

“if you had reduced housing output, you were going to have reduced taxes coming from that source and you would have to either find cuts in other areas of activity or provide for greater spend.”94

In 1998, the rate for CGT, including that in respect of gains made from the sale of development land, was cut from 40% to 20%. This increased to 60% in respect of development land if it was not developed within five years.95 The measure was designed to stimulate activity by increasing housing output which, in turn, it was anticipated would lead to price moderation in the short to medium-term.

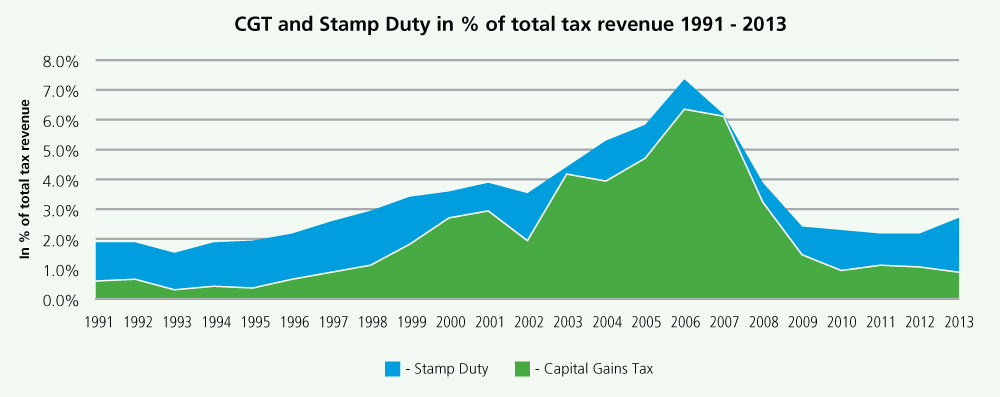

While the reduction in CGT appeared to stimulate construction output, the increased supply did not lead to the expected slowdown in house price growth96 as house price inflation accelerated from 2002. The amount of CGT received by the Exchequer increased strongly with more new developments coming onto the market and sales volumes increasing.97 From an average of less than 0.5% of total revenues between 1991 and 1995, CGT income gradually increased as a proportion of total revenue to over 2% in 2002, peaking at almost 7%, or approximately €3.1bn in 2006.98

Between 1991 and 1995, Stamp Duty contributed 2% to the total annual tax take. With the increasing number and value of property transactions and, notwithstanding some reductions in the rates, the contribution of Stamp Duty taxes to total tax revenue rose to over 3% in 1998, and reached 7.4% or €3.6bn in 2006.

The graph below illustrates how increasing revenues from Stamp Duty and CGT enabled reliance on personal Income Tax to diminish proportionately from 1997 to 2007.

Source: Tax bae erosion Ireland based on OECD stats99

Higher consumer spending was an indirect effect of rising house prices, as equity release loans on properties and a ‘feel-good-factor’or “wealth effect” generated demand for consumables such as household goods and new cars. As a result of this uplift in personal spending, income from VAT increased by over 45% to more than €14.3 billion between 2003 and 2007.

Between 2007 and 2009, total tax revenue fell by 28%, reflecting the sharp economic downturn. This downturn was most noticeable in the contribution of cyclical taxes to total revenue, which reduced from a peak of almost 30% in 2006 to 16% in 2009; a level it remained at for the following 4 years.100

Property tax incentives have always played a part in Government strategy to stimulate development, either in designated geographic areas or specific sectors of the economy.

Mortgage interest relief and low stamp duty rates for private borrowers supported not only residential house building for owner-occupiers, but also for investment purposes in times when demand for houses exceeded all long term estimates of requirement.

During the 1990s until their eventual phasing out from 2006, tax incentives served both to stimulate investment and to reduce the tax base.101

‘Section 23’ type property tax incentives were introduced in 1986 and continued for many years, through both area-based tax schemes and property-related incentives. This section describes these schemes in more detail.

This particularly significant area-based tax incentive scheme was introduced in 1986 and was targeted at areas of dereliction in 5 cities, following population declines in preceding decades. In the late 1980s, the construction industry was in difficulty and this scheme helped to both modernise derelict areas and support the construction industry. Over its duration the Urban Renewal Scheme was extended twice, to 49 areas in over 40 towns, and it was in place until 2006.102

This area-based scheme was introduced in 1998 to help develop the upper Shannon region, including counties Cavan, Leitrim, Roscommon, Longford and Sligo. While this Scheme also had strong uptake and provided for employment and new housing in relatively underdeveloped areas, it had little demographic impact. New houses were mostly occupied by existing residents of the area or left vacant. The scheme covered vast areas without the requirement for feasibility studies into the need for specific new developments. The result was that projects were often carried out for short-term employment and tax purposes, rather than to meet a real demand for infrastructural projects.103

First proposed in 2000 and introduced in April 2001, the uptake of tax incentives under this scheme was relatively low compared to the Urban and Rural Renewal Schemes.104

First introduced in 2001 and extended from the original closing date of 31 December 2004 to a new end date of 31 July 2006, these schemes were aimed at tackling the problem of vacant upper storey space in certain targeted streets in Dublin, Cork, Galway, Limerick and Waterford.105

Tax reliefs and capital allowances were also granted for a number of other types of property transactions considered important to economic development.106

A report entitled “An Economic Assessment of Recent House Price Developments”was presented to the Minister for Housing and Urban Renewal in April 1998. This report proposed specific policy initiatives including the repeal of section 23 relief for investment in residential property.107

Peter Bacon, who gave evidence during the Context Phase of the Inquiry, referred to the acceleration in house prices from 1993 and the annual rate of increase which reached 25% in 1997.108

The Government commissioned three reports between 1998 and 2000 from Peter Bacon, commonly known as the ‘Bacon Reports’.The reports recommended the adoption of a series of measures aimed at curtailing the role of investors in the property market as well as encouraging supply and enhancing affordability for first-time buyers and owner-occupiers.109 The sustained growth in property was attributed in the reports to real growth in disposable income per capita, falling interest rates and an increasing net inward flow of migrants. The main Bacon Report recommendations were subsequently implemented by the Government with the aim of curtailing investors and encouraging supply.110

In addition to these measures some section 23 tax reliefs were restricted.

When the Bacon Report recommendations were implemented, house price inflation started to come under control in 2001.111 The majority of property tax incentives had originally been scheduled to be abolished in 2002. However, after representations from interested parties, some of the measures that had been put in place to abolish these tax incentives were reversed in 2001, after Charlie McCreevy announced that CGT would remain at 20% and stamp duty for investors would be reduced. Charlie McCreevy clarified:

“Finance Bills, as is common with other legislation, are the subject of a Memorandum for government and said Memorandum would rehearse the reasons and rationales for particular sections. Decisions are then taken collectively by the Cabinet. … In my Budget speech for Budget 2002. … I signalled the proposed change for the Finance Bill 2002;

I am also aware of the difficulties being encountered in completing projects under various tax relief schemes for property investment. Therefore, I am extending the deadlines for eligible programmes under the Urban and Rural Renewal Schemes, the capital reliefs for student housing and the park and ride and multi-story car park schemes, these deadlines are being extended by two years or so, that is, to end 2004 in most cases.”112

When questioned as to why Charlie McCreevy rejected the Department of Finance’s advice to end property tax reliefs, Donal McNally said: “Well, I think the Minister was persuaded by representations that some of these schemes should continue, that they were a work in progress.”When asked from whom these representations came from he replied: “Well, in general, they would be from people who are making use of the reliefs.”113

In December 2001, Charlie McCreevy also restored interest relief as a deductible tax expense.

Peter Bacon said that section 23 tax reliefs were not necessary because there was no need to incentivise activity in a market where demand was so buoyant and he said that he advised Charlie McCreevy of this view.114 Charlie McCreevy said that the Government#8217;s view was that the continuation of these tax incentives was necessary to “maintain”the construction industry. Indeed, Charlie McCreevy suggested “that the effect of what we (had) done in Bacon No. 1, in particular, was in danger of killing off the whole construction activity.”115

Instead of cutting tax incentives in the 2002 Budget, most of the tax reliefs were extended until the end of 2004. This was reconfirmed in Budget 2003, with the clear statement that no further time extensions would be given in respect of the tax schemes.116 Despite this, in the Budget for 2004, Charlie McCreevy announced a further extension of all area-based tax incentives to the end of 2006, effectively leaving future decisions on such matters for the next Minister for Finance, Brian Cowen, who took that office in September 2004.

At the time, some commentators, such as Professor John FitzGerald, recommended a much earlier end to the Government’s property related tax incentives:

“In addition to operating a much tighter fiscal policy in the 2001-07 period, I recommended using specific fiscal instruments to take the heat out of the building and construction sector. We recommended getting rid of all building incentives and, possibly, taxing mortgage interest payments.”117

It was argued by Charlie McCreevy, Brian Cowen and Bertie Ahern, that builders and investors had committed themselves to various schemes and needed reasonable transitional arrangements to unwind and/or complete projects.118 We also heard that heavy lobbying was a factor in the extension of the incentives in the Budget of 2004.119

Alan Dukes, Director and Chairman of the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation said in relation to the construction sector:

“for many, many years the construction sector in Ireland has persuaded all political parties… on the basic proposition that they make that construction is good for the economy. I’ve always thought that that is the wrong causation. A strong economy is good for construction and I think that an over-reliance on construction as a motor of growth has turned out, in our case and indeed in other economies, to be a very bad idea.”120

Donal McNally talked briefly about the use of tax incentives in construction for high net-worth individuals. He told us:

“…in 1996 and 1997… We did persuade [Revenue] to do a survey of the top 400 earners, trying to find out which reliefs were being used or not. And, you know, the conclusion was that these were favouring those with the money to invest and with the taxable income to offset it against and as a result … and those reviews are published each year, but there was a change made in 1998 Finance Act which limited the amount that could be set off by passive investors against other income. So, you know, it was known that these reliefs benefited high earners, yes.“121

We asked Charlie McCreevy about the benefits of these tax incentives for high net-worth individuals. The following statement was put to him by the Joint Committee:

“of the 400 top earners in Ireland during 2002 and 2001 [which showed] the way that they were able to reduce their effective tax rate was through these schemes…For example, there were six individuals of the top 400 earners that paid no tax in 2002, which was an increase from 2001. There was 37 of the 400 that paid between 0% and 5% effective tax rate. That was an increase from 25 the year before.”122

We said that these “individuals were able to reduce their tax rate, in some cases, to a level of zero”as a result of these property schemes and invited Charlie McCreevy to comment.

Charlie McCreevy responded:

“Successive Finance Ministers, pre my period and during my period, have introduced changes into the taxation code to ensure that everyone is trying to … that everyone is paying an adequate level of tax.”123

Another possible reason for the extension of tax incentives, or at least for the reluctance to cut off tax incentives immediately, was that revenue from CGT and Stamp Duty had risen strongly since 1998 as evident from the graph below. This was partly due to the fact that tax incentives led to the continuation of the strong activities in the property and real estate sector. An end to tax incentives would have resulted in a reduction in tax revenues from these two sources.124 The resultant impact on the SGP and other benchmarks could have been significant.

Source of Statistics: OECD 125

On appointment as Minister for Finance, Brian Cowen commissioned a comprehensive review of property tax incentives in late 2004.126 Arising from these reviews, two reports were completed in 2005 and they recommended the complete or partial elimination of the majority of tax schemes. The reports found that most tax schemes were too expensive for the Exchequer, relative to the benefits they produced. In some cases, even the benefits were doubtful. It was also found that, up to the end of 2006, the estimated cost of area-based schemes to the Exchequer was €1.93 billion. The overall cost for property-based incentives for the period 2005 to 2008 was in the region of €453 million.127

These reports also indicated that property incentives contributed to property price inflation, largely benefitting a small number of landowners and developers. Average house prices grew at a proportionately greater rate than the average industrial wage in six out of eight years from 1998-2006.128 The Goodbody Report suggested that the schemes had a strong negative effect on income distribution.129

The Goodbody Report also provided Government with the quantification of the costs of the schemes to the Exchequer and highlighted that some 74% of the potential revenue lost by reason of the tax breaks came from a single incentive, the Urban Renewal Scheme.130

In his clarification statement, former Finance Minister and Taoiseach, Brian Cowen said that property-based tax incentive schemes, which were due to be phased out in July 2006 and closed to new projects, were extended to 2008. “Two independent reviews were carried out in 2005, and published in February 2006 alongside Budget 2006”he said. “Goodbody Economic Consultants were retained in April 2005 to undertake a detailed review of the area-based tax incentive schemes: the Urban Renewal Scheme (URS), Rural Renewal Scheme (RRS), Town Renewal Scheme (TRS) and Living-Over-the-Shop Scheme (LOTS)”while “Indecon economic consultants were retained in April 2005 to undertake a detailed review of various sectoral property-based tax incentive schemes.”The reports, according to Brian Cowen, found:

“Following analysis of the reviews received from these consultants, it was recommended that the following property-based tax incentive schemes, which were closed to new projects but included applicable construction activity up to July 2006, should be allowed to expire, subject to an extended phasing-out period for existing pipeline projects out to 2008: the Area-based Renewal Schemes (Urban, Town and Rural Renewal); Several of the sectoral incentive schemes, namely reliefs for hotels, holiday cottages, student accommodation, third-level buildings, multi-storey carparks, developments associated with park-and-ride facilities.”131

The extension of tax beyond the mid-1990s however, meant that the Government supported a large number of economically self-sufficient development projects with further monetary incentives.132 On top of that, many residential developments were subsidised in areas where no real demand for housing existed133 and for which realistic demand studies had not been carried out prior to their commencement.

The extent to which the oversupply of housing had been supported through tax incentives became clear in 2009, when completion of residential units reduced to 26,420, from over 93,000 in 2006, a fall of 72%.134 However, in 2008, the Government had only budgeted for a drop in housing completions to 45,000.135

In evidence, Bertie Ahern acknowledged that the reliefs in relation to the construction sector had helped create and sustain the property bubble. He said that he came to that view in about 2009.136

The tax incentive which was mostly widely taken up was the Special Savings Incentive Account (SSIA) scheme which attracted over 1.1 million savers when it was opened in 2001 and 2002. Overall, an amount of €10 - €12 billion was saved by individuals over a five year period up to 2007.

Charlie McCreevy was very clear that, despite the lack of analysis that was done prior to the launch of the SSIA Scheme, he was content with the results of the scheme. Indeed he said:

“…that was a counter-cyclical policy … it must have taken in the order, over the five years … if it cost €2.5 billion, it must have taken in the order of €10 or €11 billion out of the economy over the five years.”137

However, a further consequence of the SSIA Scheme was that the money saved flowed back into the economy plus the 25% added on by the Government. SSIA plans expired between May 2006 and April 2007 with no Government plan or policy to deal with changed consumer habits or approach to best channel the maturing funds. The Central Bank’s Financial Stability Report of 2006138 referred to some estimates that approximately 33% of the total saved ended up being spent on cars and holidays together (up to €4 billion) and home improvement (up to €1 billion) in those two years.

The Economic and Financial Affairs (ECOFIN) Council is responsible for EU policy in three main areas:

The Government, through the Minister for Finance and senior officials, interacted on a regular basis with its peers in Europe via ECOFIN. It was there the Government’s position could be discussed in more detail and commentary could be received from the ECOFIN Council on their view of Government performance and actions.

The ECOFIN Council coordinates Member States' economic policies, furthers the convergence of their economic performance and monitors their budgetary policies.

One significant impact which the ECOFIN Council had on all Member States, including Ireland, was the requirement to adhere to the terms of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) (see Chapter 3).

The European Commission is charged with enforcing the SGP terms and breaches are liable to economic sanction. As part of the SGP enforcement regime, Member States are obliged to present a SGP report in the form of a Stability Programme to the ECOFIN Council.

The Irish Government drew too much comfort from their budgetary strategy being in regular compliance with the terms of the SGP rather than upon analysis of the underlying correlated risks in the economy. However, this sense of security was ultimately misplaced as the existing Structural Deficit was unidentified in the period up to 2008.

Participants at informal ECOFIN Council meetings include the Finance and Economy Ministers and Governors of the Central Banks of EU member states. These informal meetings usually served as a platform for new initiatives and discussions on topical issues in the field of economics and financial affairs.

Typically, the Minister for Finance receives a briefing on these meetings, which includes speaking notes on different subject matters.

The speaking notes prepared for the Minister for Finance, by the Department of Finance, were constructed to give a positive public message, such as those relating to the September 2003 informal ECOFIN meeting which stated: “While the banking sector has a high exposure to residential property, a steep decline in the Irish property market is unlikely.”139

Yet in the same speaking note, there was awareness of the risk associated with commercial property prices: “…commercial property prices remain a potential source of vulnerability for the Irish banking system…”140

This pattern of a reassuring tone is repeated in speaking notes in 2004 & 2005.

“Irish banks remain well capitalised with solvency ratios significantly in excess of the regulatory minimum.”141

“The Irish banking sector is currently in a strong position, with good profitability and reserves well above minimum requirements.”142

Further assurances were given by Brian Cowen regarding the stability of the financial sector at the 2005 informal ECOFIN meetings. At the meeting in May 2005, his speaking notes included the following statement:

“The national authorities in Ireland - the Department of Finance, the CBFSAI and IFSRA - are currently actively cooperating to put in place appropriate procedures and arrangements to ensure that the Irish authorities can respond speedily and effectively to any emerging or actual financial crisis in Ireland.”143

The Minister’s briefing for the September 2005 meeting provided the following further reassurance: “The available information suggests that the banking system remains in robust health.”144

Despite the continued emphasis on the need for appropriate monitoring of risk in the financial sector, Ireland continued to display confidence in its regulatory regime. For example, Brian Cowen’s speaking note at the May 2005 informal ECOFIN Council meeting said: “In short, we supervise banking and other financial activities to the highest European and International standards.”145

However, this sentiment changed when, at the April 2006 informal ECOFIN Council meeting, the Minister’s speaking note noted that rising house prices had been highlighted as a potential source of instability, due to the possible over-exposure of the banks in this sector.146

The European Finance Committee, in its November 2007 report to the ECOFIN Council, stressed the need for prudence in the valuation and accounting treatment of assets “…particularly of those assets where markets are potentially illiquid in time of stress…”147

Having examined how the macro-economic policies and decisions of Government helped create the conditions for both the boom and the crash, it is necessary to explore the effectiveness of oversight by the Oireachtas, its constituent parts, and its ability to influence unfolding events.

Given the change in circumstances that the State and its citizens have experienced, it is appropriate to look at the Oireachtas of the day and its role in this crisis and how decisions were made.

The Oireachtas comprises two houses, the Dáil and the Seanad, which currently have 166 and 60 members respectively. The principal role of the Oireachtas is to enact legislation. The Dáil is responsible for nominating the Taoiseach, the head of the Government, by a simple majority. The Taoiseach (through the President) appoints the various Ministers who have control over their respective Departments. The Taoiseach and Ministers make up the Government. The Taoiseach generally requires the support of a majority of the members of the Dáil to govern. If it loses this support the Ministers are obliged to resign from office unless the Dáil is dissolved. Members of the Dáil who are not members of the parties which make up the Government constitute the Opposition. Under the Irish Constitution (Bunreacht na hÉireann), the Government is responsible to Dáil Éireann.

The Committee heard evidence from Professor David Farrell, UCD, in relation to public policy in parliamentary democracies. He outlined 3 factors for an effective parliamentary democracy:148

His view was that the Oireachtas had

“…performed poorly … It lacked sufficient organisational and structural fire power to provide effective scrutiny. It lacked the political will to use what powers it did have, indicating what I call cultural shortcomings, and it was hindered by a governmental system that places great emphasis on secrecy, particularly in its dealings regarding budgetary matters. There is little evidence to this day that those matters have been resolved.”149

The weaknesses in the Irish system have been noted at various times in the past, with different reports having called for changes to improve parliamentary scrutiny and increases in parliamentary support for members to assist them in their tasks. In his witness statement to the Inquiry, Pat Rabbitte, former Minister, drew attention to these limitations and also recommendations made in previous Parliamentary reports to address them, including the DIRT report, 19 July 1999, and a report prepared for the Public Accounts Committee in 2005.150

The key political leaders during the relevant period responded in different ways when questioned on their own degree of responsibility.

Brian Cowen accepted the responsibility that goes with his role as a decision maker but did not accept that that there was “a mismanagement of the economy by us.”151

Bertie Ahern accepted that “…the amount of taxation that was directly related to…property was too high.”152 He accepted responsibility for the structure of regulation brought in by the Central Bank Act of 2003, but stated “I take no responsibility… for what was happening in the Central Bank or in the Financial Regulator because I had no knowledge or control over it.”153

Charlie McCreevy, when asked whether he “should take any share of the responsibility for the crisis that emerged”four years after he left office, responded:

“… you would only apologise for things that you think you got very much wrong or you made a mistake, or a big mistake or a series of large mistakes. I don’t believe that I did.”154

A common theme amongst witnesses was that it was the responsibility of the Central Bank and Financial Regulator to monitor what was going on in the banks and senior Government figures would be unware of the financial condition the banking sector was in. Brian Cowen said:

“It is, however, important to note that no one in the independent authorities ever advised the Government that the capital adequacy was not sufficient or that higher capital adequacy ratios should be imposed.”155

The regulatory system was significantly changed with the passage of the CBFSAI Bill in 2003. In anticipation of these changes, Brian Patterson was appointed Chairman of the Financial Regulator (initially in an interim capacity, from April 2002) by Charlie McCreevy. Brian Patterson stated in his evidence: “the only person who could have set objectives and goals for me probably would have been the Minister and he didn’t do that.”156

Charlie McCreevy was asked to respond to this statement. He stated: “I went in September 2004. I wouldn’t have had time to monitor what was being set there for the regulator because it was too early in the process.”157

Patrick Neary was questioned on whether there was any review of the new structure following its introduction to assess its effectiveness. He accepted that no review was carried out domestically (by the CBFSAI, the Government or the Department of Finance), but said:

“The Authority’s approach, in the same way as that of other country’s banking supervisors, was subject to ongoing best practice review and external assessment by international bodies such as the IMF and OECD. These agencies benchmarked, in detail, the Authority against a framework of principles entitled “Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision.”158

The Financial Stability Reports and annual pre-budget letter from the Governor formed the basis for the Governor’s discussion with the Minister(s) for Finance.159 (See Chapter 3). Previously this information had been incorporated in the Annual Reports.160 Brian Patterson, the Chairman of IFSRA from 2003 to 2008, described the reports as the main mechanism for the Central Bank and IFSRA to communicate the macroeconomic situation to the Government.161 John Hurley was asked whether there were other mechanisms apart from the Financial Stability Reports and the Pre-Budget letters to ensure the Central Bank kept the Government informed about the current macroeconomic situation and the effects of macroeconomic developments on the financial stability of the banking sector. In response, he outlined the following actions: “ ... the risk assessment of the Central Bank on financial stability matters was communicated primarily by means of the Financial Stability reports published by the Central Bank, the introductory statements of the Governor at their launch and the press conferences themselves … They were addressed in the regular meetings between the Minister and Governor and in the pre-budget letters sent to the Minister for Finance. They were also communicated in meetings between the Taoiseach and Governor … In addition the Bank’s views were communicated by means of its Quarterly bulletins and its Annual Reports which were submitted to the Government. These reports also received wide media coverage …“162

Describing contacts between the Minister for Finance and the Central Bank, Charlie McCreevy stated: “I met formally with the Governor every two months approximately. Also, I met him on other occasions throughout the year.”163 John Hurley confirmed that “The financial stability reports were discussed by me with the Minister on many occasions.”164

Brian Cowen gave evidence of meeting with the Governor when the Financial Stability Reports and Pre-Budget letters were produced. He also referred to his meetings with the Financial Regulator as follows:

“I would have expected that any concerns would initially be escalated through the existing channels of the Central Bank and Financial Regulator through the Secretary General of the Department. Any briefings I received from the Governor of the Central Bank and through the financial stability reports were overall conclusively positive.”165

Brian Cowen gave evidence that he met the Chairman of the Financial Regulator approximately twice a year. He stated:

“…if there was any issue at any time that the chairman of the Financial Services Authority wanted to bring to my attention, there was no problem bringing it to my attention.”166

Brian Patterson, Chairman of the Financial Regulator from 2003 to 2008, stated that his meetings with the Minister for Finance were:

“…less to kind of report to the Minister, in some sort of supervisory capacity; it was more to keep the Minister informed with, for example, EU developments, directives and so on.”167

Bertie Ahern stated, when questioned on whether he discussed the content of the Financial Stability Reports with the Minister for Finance: “I met the Minister for Finance several times a week, so he would always be updating you and briefing you on issues that happened and meetings that happened.”168

The evidence would indicate that the Central Bank was providing the Government with information on the macroeconomic situation and financial stability on a frequent basis, through the medium of the Financial Stability Reports, the Quarterly Bulletins and the pre-budget letters. The Minister for Finance also met regularly throughout the year with the Governor of the Central Bank and on a more limited basis, with the Chairman of the Financial Regulator. There were clear channels of communication for the Minister and the Central Bank to discuss issues relating to financial stability and macro-economic problems.169 When asked whether he challenged the assertion that the risks highlighted in Financial Stability Reports could be managed strongly enough, Brian Cowen did accept that “Clearly, it wasn’t questioned sufficiently and I accepted the consensus view.”170

The Opposition, as well as being able to promote their own agenda, had a valuable role to play in a parliamentary democracy by scrutinising the work of the Government and holding it to account.

As well as contributing to debates, issues may be raised through Parliamentary Questions which must be addressed by the Taoiseach or relevant Minister. Several hundred such questions are typically tabled in a parliamentary session.

Enda Kenny, Taoiseach, and former Leader of the Opposition, was asked to explain why, during the 43 Fine Gael different private member “slots”in the Dáil between 2005 and 2007, he or his party did not choose to use those slots to address the system of regulating banks, lending related to property or excessive public spending. In response, he stated these questions were not the only opportunity to raise important issues:

“So…the Private Members’ business is an opportunity for parties and, obviously, backbench Deputies and Front Bench Deputies want to raise issues that might be of more local than national importance.”171

Brian Cowen summed up his view on the effectiveness of the Oireachtas in his opening statement. He said:

“…throughout my period as Minister for Finance the critique from the political Opposition was that we were not addressing economic issues quickly enough. There were constant demands for more spending. The capital adequacy, or otherwise, of banks, was not, to my knowledge, ever raised as a priority issue.“172

Brian Cowen was asked to comment on why there was so little scrutiny in the Oireachtas, and he responded:

“I think that just there was a belief in good times that banks seemed to be a good business to be in and they seemed to be doing well and there was no indication that they were in trouble. And, as I say, this silently … this misjudgement of risk is what’s behind all of these miscalculations from a whole slew of actors.”173

On macroeconomic and fiscal policies, the most robust and sustained engagement between Opposition and Government took place around the introduction of Budgets, but this tended to focus more on spending and taxation choices rather than macroeconomic policy. Bertie Ahern was asked whether he was aware of concerns raised with the Minister for Finance by the Opposition TDs in the Dáil in 2007 and whether he paid attention to them. Bertie Ahern said:

“I’ve read the questions…but I’d have to say…do I think 2008 was too high in public spending, the answer is yes. Did I listen to the Opposition in the House, I would have spent three times more if I’d listened to them.”174

A number of major fiscal issues were introduced by the Government during the pre-crisis years, which had major long-term budgetary impacts, but were not open to rigorous scrutiny by the Oireachtas. Amongst the most notable of these were the public sector benchmarking exercises of 2002 and 2007.

Then Finance Spokesperson for Fine Gael, Richard Bruton noted: “Government did not even see the need to bring Social Partnership agreements to the Dáil for democratic approval.”175

Enda Kenny said:

“…the lack of opportunity for the Oireachtas to properly scrutinise and assess the tax and spending options available to the Government were a very sore point with us”; “…Our opposition to the Governments public sector benchmarking pay deal reflecting the lack of transparent…”176

Former Chair of the Public Accounts Committee, Bernard Allen stated that “all negotiations with the social partners were conducted in secret and there was no role for the Oireachtas.”177 He also noted that the Public Accounts Committee was prohibited from carrying out analysis of budgetary policy under Standing Order 163(7).

Former Tánaiste, Mary Harney noted in her statement to the Joint Committee: “There were many positive outcomes from Partnership but the model became all-embracing and, to an extent, undermining of the role of the Oireachtas.”178

The Joint Committee noted limited engagement with senior management in key state bodies such as the Department of Finance, the Financial Regulator and the Central Bank. Enda Kenny confirmed to the Joint Committee that he had never had meetings with staff or officials from the Central Bank or the Financial Regulator in the period 2002-2007 though he never sought such meetings.179

Witnesses before the Joint Committee gave evidence as to how effectively they thought the Oireachtas discharged its duties. Mary Harney noted in her statement:

“In truth, the quality of Oireachtas oversight of banking and economic policy was very poor prior to the crisis. Oireachtas committees that could have had a role were low profile and in my opinion did little real analysis of economic policy and none at all on banking policy.”180

Richard Bruton said: “I think it wasn’t well-equipped, neither in having access to the information nor the analytical armoury at its disposal.”181

For efficient working of the Oireachtas, tasks are delegated to Committees, who shadow Government Departments and examine legislation and spending. These committees are drawn from members of the Oireachtas, either Select (from one House) or Joint (from both Houses).

Membership of the Committees may be drawn from all members of the Oireachtas except Government Ministers.

The role of Committees within the Oireachtas has been expanded in recent years. An examination of the records of Committee hearings suggests that Joint Oireachtas Committees are structurally more amenable to conducting an inquiry than those restricted to TDs only.

We sought evidence from a number of former Chairs of Oireachtas Committees. They provided varying views and some constructive criticism on the effectiveness of the Committee system and suggested improvements.

Former Chair of the Joint Committee on Finance and the Public Sector, Michael Ahern said, in relation to the lack of experience and expertise on the Committee, “However, what was an issue and a limitation was the resources the Committee had; how could 11 Deputies and 4 Senators oversee such a huge remit?”182

Bernard Allen said:

“My own experience is that there is very little independent advice available to Oireachtas Members. For the most of my years in the Dáil, there was not the scope to get that independent expert advice.”183

Former Chair of the Joint Committee on Finance & Public Service, Seán Fleming said:

“Essentially the Oireachtas Committees had little or no access to additional expert advice. They essentially relied on officials from the relevant Government Departments to provide information”184

Michael Ahern also spoke of the lack of available expertise and suggested, “An Office like the Office for Budget Responsibility is necessary.”185

Former Leader of the Labour Party and Minister, Pat Rabbitte, spoke of the difficulty in finding specialisation amongst a Parliament of 158 Deputies and added: “Individual Deputies being members of more than one or of several Committees compounds the problem.”186

Other witnesses were less critical. Former of the Chair Joint Committee on Economic Regulatory Affairs, Michael Moynihan in his statement said:

“Our committee was given a specific remit in the context of annual reports and public interest statements. We fulfilled this remit but it is obvious in retrospect that the remit of the Committees should and could have been wider, and then expertise could be requested. I do not recollect being asked to bring in expert advice and I am quite confident if the need was there it would have been supplied.”187

Bertie Ahern also said:

“I think the committees did their best. And, I think, one of the advantages of the committees is that they can call people in and they can discuss it but, as you recall, Deputy, there were very … there was very little debate on these issues in the Oireachtas.”188

Former Tánaiste Mary Coughlan stated:

“Both as a back-bench Teachta Dála and as a Minister, it was my experience that committees were appropriately resourced to obtain such expert advice as any such committee deemed necessary to assist it with its enquiries.”189

In the years preceding the crisis, the capacity of the Oireachtas Committees was restricted by a number of factors:

These restrictions still exist. The Committee system has evolved and developed over a number of years to its current construct. This evolution did not include an objective review, and implementation of, recommendations in relation to improving its oversight and effectiveness.

Each new Government, when elected, agrees a Programme for Government, which would have been influenced by the Election Manifestos of the participating parties. Pre-2008 party political election manifestos examined by us contained a variety of promises on taxation and spending.193

In 2002, the common focus was on increasing expenditure, but not raising taxes. This plan depended on expected economic growth materialising. The vulnerability of this approach of course would be agreeing increased expenditure plans based on anticipated income, which may not materialise.

In its 2002 manifesto, Fine Gael194 had some limited costings done, which was absent from the manifesto of Fianna Fáil.195 While there were different approaches in detail and emphasis, the underlying construct for all the 2007 manifestos was premised on cuts in taxation and increases in expenditure.196

The Fine Gael Manifesto promised to cut taxes for all taxpayers and increase current exchequer spending by an average of 6% per annum. Fianna Fáil’s manifesto also promised 6% spending growth. Its spending plans assumed 7% nominal growth in the economy annually and employment growing by 2.5% per annum. This would deliver average budget surpluses over the following 5 years and a Net Debt/GDP ratio of 3% by 2012. The Labour Party approach was to detail the various additional services that would be funded but provide no costings. Tax cuts were also promised.197

When questioned at Committee on why the Fine Gael election manifesto also put forward proposals to reduce taxes in 2007, thus narrowing the tax base, Enda Kenny replied that the commitments on tax and spending were:

“… consistent on the basis of the growth forecasts that were available at the time, both from the ESRI and from the Department of Finance, which were forecasting growth average of about 4%, between the period 2008 to 2012.”198

Joan Burton, Tánaiste and former Finance spokesperson for Labour, also referred to the ESRI and Department of Finance growth forecasts when questioned on the Labour Party 2007 election manifesto promises for taxation and spending.199

Klaus Regling, former Director-General for Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission, summed up the position in his evidence when he noted several interacting factors:

“…weak financial supervision and bank governance combined with official policies to leave the economy vulnerable to a deep crisis.”200

He also said:

“Ireland was a country where it seems no one was really in charge to prevent such a bubble from emerging over the previous four to five years that led to 2008.”201

The erosion of the income tax base in the years leading up to the crisis did not give rise to sufficient concern at Government level at the time, primarily for two reasons:

i) the significant increases in transaction taxes, such as stamp duty and capital gains tax, which compensated for the declining share of income tax as a proportion of total tax revenue.

ii) the absolute increase in income tax revenue from approximately €4 billion in 1990 to €15 billion in 2007.

Chapter 5 Footnotes

1. Nyberg Report, Misjudging Risk: Cause of the Systemic Banking Crisis In Ireland, March 2011, PUB00156-022.

2. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-141.

3. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript PUB00345-003.

4. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-069.

5. Glossary: Structural deficit.

6. Derek Moran, Secretary General and former Assistant Secretary, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00114-006/007; John Moran, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, JMO00002-002.

7. Statistics show that Capital Gains Tax income grew from €56m in 1995 to €3.099m in 2006. (dataset: Details of tax revenue Ireland) Stamp Duty rose from €279m in 1995 to €3.576m in 2006, PUB00402-001. This is considered below at Section 1.

8. John FitzGerald, Research Affiliate, former Research Professor, ESRI, statement CTX00022-013; Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, CTX00057-025.

9. Bertie Ahern, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00109-004; Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-011.

10. Bertie Ahern, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00109-004,022; Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-004; Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-008/027.

11. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-023.

12. John McCarthy, Chief Economist, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00128-003.

13. GDP at market prices, PUB00400-001.

14. CSO-.Eurostat database, table [nama_10_gdp] Gross Domestic Product at market prices, updated 10 September 2015. PUB00400-001.

15. Ireland and Europe Statistics on Debt/GDP deficit, PUB00400-001.

16. Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-005/006.

17. Bertie Ahern, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00109-024.

18. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-122.

19. Tom Considine, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00112-004.

20. Derek Moran, Secretary General and former Assistant Secretary, Department of Finance, statement, DMO00001-010.

21. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-004/019/023.

22. A detailed account of the European commission’s monitoring of Ireland’s economic performance throughout this period provided by Marco Buti CTX00057-004 to 007.

23. Eurostat national accounts database, Government deficit/surplus, debt and associated data [gov_10dd_edpt1] as per update on 17th June 2015, PUB00400-001.

24. Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-006; Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-019.

25. Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-070.

26. CSO/StatBank Table QNQ24, PUB00398.

27. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-010.

28. CSO/Components of population change, PUB00401-001.

29. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-019/041; Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-006.

30. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-019.

31. Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-006.

32. CSO/StatBank Table QNQ24, PUB00398.

33. Annual Construction Industry Review, 2009, PUB00235-065.

34. John FitzGerald, Research Affiliate, former Research Professor, ESRI, transcript, PUB00287-004; John Moran, Managing Director, Jones Lang LaSalle Ireland, transcript, CTX00047-003.

35. Bertie Ahern, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00109-058.

36. Bertie Ahern, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00109-013.

37. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, ANO00002-001.

38. Rob Wright, former Canadian Deputy Minister, author of the report ‘Strengthening the capacity of the Department of Finance’, CTX00058-005; PUB00175-024; IMF Country Report Ireland, No 04/348, PUB00138-049.

39. John McCarthy, Chief Economist, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00128-003.

40. ‘Strengthening the capacity of the Department of Finance, Report of the Independent Review Panel’, December 2010, PUB00175-025; Pre-Budget Letter from John Hurley to Charlie McCreevy 30th September 2003, INQ00070.

41. Dermot McCarthy, Secretary General, Department of the Taoiseach, transcript, INQ00108-041.

42. Department of Finance, Summary of the Central Bank Autumn Bulletin – 3rd October 2002, DOF01034-002; Department of Finance Summary OECD Autumn 2002 Economic Forecasts, DOF01066-001.

43. CSO, Ireland, StatBank table QNQ03 shows that total number of employed increased from 1.71mln in Q1 2001, to 2.17mln in Q3 2007. Number employed in construction increased from 0.17mln to 0.27mln, PUB00398-001.

44. IMF Country Report Ireland, No 04/349, November 2004, PUB00138-048.

45. Organisational Review Programme – Third Report, PUB00353-180/181.

46. Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-033.

47. Rob Wright, former Canadian Deputy Minister, author of the report ‘Strengthening the capacity of the Department of Finance’, transcript, CTX00058-004/006.

48. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-069.

49. Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-071.

50. Bertie Ahern, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00109-054.

51. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00345-138/139.

52. Tom Considine, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00112-033.

53. Charlie McCreevy, former Minister for Finance, transcript, PUB00346-004.