Back to Chapter 8: Post-Guarantee Developments

In early 2009, the financial and construction sectors were at a standstill, with banks and developers alike dealing with the consequences of a liquidity crunch and an inflated property market. The Minister for Finance and his advisors1 had growing concerns over the capacity of the covered financial institutions to meet their future obligations, especially given their inability to raise adequate capital.2 Steps were taken to stabilise the financial system, alleviate doubts over capital adequacy and boost the capacity of the financial institutions both to deal with prospective loan impairments and to lend.

The economist, Peter Bacon, was engaged by the NTMA, on the instructions of the then Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, to evaluate the options for resolving property loan impairments and the associated capital adequacy of the covered financial institutions. His detailed report3 was completed in March 2009 and outlined three options:

From the outset, the ‘status quo’ option was not considered feasible by Government. The consensus among the Department of Finance, the Central Bank, the Financial Regulator, the NTMA and Merrill Lynch was strongly in favour of the establishment of an asset management agency, even though the insurance scheme would have deferred the realisation of impairments and have involved less upfront costs.7

However, none of the options were underpinned by robust knowledge on the status of the property-related loans held by the Covered Institutions which, on transfer to NAMA, came to be characterised by a paucity of loan information, high levels of debtor concentrations and poor loan collateral. In his evidence, Peter Bacon commented that:

“… [NAMA] subjected each and every loan to rigorous scrutiny. I would not have been party, at an individual level, to knowing what the security behind those loans was or what they were worth. There would have been all kinds of cross-guarantees at an individual level, which, working from macro data, one would not have had access to or knowledge of.”8

When Peter Bacon and the NTMA presented the NAMA proposal to the Minister and Department of Finance officials, it “came as something of a shock”given its ambition and “the size of the proposed contingent liability to be adopted by the State”, according to the evidence of Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General of the Department of Finance.9 Peter Bacon recalled presenting the report, saying:

“I remember the response when I presented the figures in my report. There was a standing committee, chaired by the Minister, comprising the suspects one would expect - Finance, Central Bank and NTMA. I was invited to attend one of those and the Minister asked how my work was going and had I any numbers. I gave the meeting a work in progress account. I suppose that surprise was my memory of that meeting. Surprise from people at the numbers that were coming out.”10

The standing committee, as referred to above, were also apprehensive over the cost to the State by way of contingent liability.11 Peter Bacon, however, was concerned at how quickly the commercial property books in the covered institutions were declining and believed that these loans needed to be removed from the institutions before lending in the economy could resume.12

Support for the NAMA option was based on a number of factors:

NAMA’s establishment was announced in the “mini-budget” of spring 2009.14 From that date, it took over a year for the enabling legislation to be enacted and the loans to be transferred from the relevant institutions. The Office of the Attorney General commenced work on the legislation in April 200915 and the first tranche of loans was transferred in March 2010.16

The NAMA legislation needed to address many potential risks, while at the same time ensuring that its legal structures would enable NAMA to acquire all relevant property-related loans, obtain the underlying collateral, operate efficiently and protect taxpayer interests.17

It was also essential that NAMA would comply with the European Commission’s State Aid rules.18 This was quite a complex process, requiring the NAMA Steering Group to have ongoing consultations with the European Commission throughout the drafting process.

The draft legislation was completed in July 2009, at which time the Government decided that there should be a public consultation process. The consultation period ended in September 2009, and the legislation was enacted in November 2009.19

The scheme provided for under the NAMA Act secured the required State Aid approval from the European Commission on 26 February 2010.20

The legislation supported a number of key processes for loans to be transferred to NAMA, including:

The Joint Committee received evidence from nine of the largest developers and property investors who participated in the NAMA scheme, four of whom gave evidence in public hearing and five by written statement.

From the announcement of NAMA in April 2009 to its eventual establishment in December 2009 and the subsequent transfer of the first tranche of loans in March 2010, uncertainty in the economy was prolonged.26 There was a complete lack of liquidity in the market and financial institutions were no longer able to operate effectively. Work-in-progress on developments stopped, agreed sales fell through and the bottom fell out of the property market.

For Sean Mulryan, the prolonged uncertainty meant “that the business [Ballymore Group] didn’t operate for probably 12 months; it was just absolutely stopped.”27 The difficulties were accentuated by the fact that the majority of his business interests had been in London and the market there had little understanding of either the banking crisis in Ireland or the role that NAMA was designed to play – they had to get their “heads around”the requirement of “handing over such an enormous amount to a new entity.”28

Michael O’Flynn said that developers were caught in limbo between their existing financial institutions and NAMA.29

Joe O’Reilly commented that he “…continued to asset manage and drive the business from that point of view.”30

In his statement to the Joint Committee, Gerard Gannon said:

“Like many other parties, I was apprehensive when NAMA was established and I feared the unknown. In some respects it offered relief as the banks had ceased to function and we were finding it difficult to carry on our normal day to day activities.”31

Over the period from announcement to implementation, Participating Institutions were tasked by NAMA with completing questionnaires and organising exposures to allow for the eventual transfer of relationships. These questionnaires and related follow-up steps uncovered a number of problems such as a significant amount of interest rolled up by the Participating Institutions, widespread use of paper collateral and major reliance on solicitor’s undertakings, amongst other issues.

Kevin Cardiff said in evidence:

“…there was a real problem that the assets that NAMA was purchasing in the banking market were not turning out to have the characteristics that NAMA had been led to expect – on various measures, the loans were not as good as they should have been.”32

The property market generally also continued to deteriorate over the period.

Such issues came to be reflected in the discounts applied by NAMA to acquired loans. NAMA ultimately acquired €74.4 billion of assets for a final consideration of €31.7 billion, an average discount of 57%33 of the total amount owed by the borrowers.34

To participate in the NAMA scheme, the credit institutions had to apply to the Minister for Finance within 60 days of the establishment of NAMA.35 The Minister - in consultation with the Governor of the Central Bank and the Financial Regulator – could then decide to permit a institution to participate if the Minister was satisfied that the credit institution was systemically important to the financial system in the State and that the other requirements of the NAMA Act had been fulfilled.36 NAMA was then set the task of acquiring loans from the Participating Institutions i.e. AIB, BOI, Anglo, INBS and EBS.

NAMA’s approach was to acquire the following types of loans from each of the Participating Institutions:

It should be noted that this approach was not well received by all affected borrowers of the Participating Institutions. For example, in his evidence to the Joint Committee, Sean Mulryan of the Ballymore Group stated that:

“…[t]he reputational damage that Ballymore endured … was compounded by the fact that NAMA took over everything related to Ballymore – all loans, not just the poorer performing loans but the good loans and unencumbered assets as well.”40

Kevin Cardiff explained that an advantage of the acquisition of the complete loan portfolio from a borrower, comprising both good and bad loans, was that NAMA would be able to get more value from individual borrowers:

“they would be able to concentrate three or four of their exposures into one place and manage them as a group, rather than having them managed separately …”41

The initial threshold for loans transferring from AIB, Anglo and Bank of Ireland was €5 million. However, following consultation with the NAMA Board, the Central Bank, Financial Regulator and the European Commission, the Government decided, in September 2010, that the loan threshold should be raised to €20 million in respect of AIB and Bank of Ireland.

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach, stated that raising the threshold in this way allowed NAMA to operate to the highest level of efficiency and effectiveness in the management of the transferred loans and enabled all transfers to be completed by the end of 2010.42

NAMA also elected not to acquire certain other loans if the scale of exposure to land and development was only a nominal proportion of the borrower’s overall debt.43

In total, NAMA acquired 90% of all identified eligible loans from the Participating Institutions. The effect of this left the Institutions with a residual commercial real estate loan book, at the end of 2013, of €36.5 billion with an impairment rate of 56.9%.44

In terms of obtaining the requisite information on the acquired loans in order to facilitate due diligence, Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to Minister Lenihan, stated that:

“…the NAMA process … was going to gather very accurate information – time-consuming, but they were going to drill down and, on a loan-by-loan basis, get the sort of information that, ultimately, you needed.”45

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Brendan McDonagh, Chief Executive Officer of NAMA, commented: “[The banks’] issue was trying to compile the data together for the due diligence, which was very difficult for them.”46

This view was supported in evidence provided by witnesses from two of the Participating Institutions. Kieran Bennett, former Chief Risk Officer with AIB, stated that:

“AIB’s credit management information and stress test systems were poor and required considerable investment.”47

Ronan Murphy, former Group Chief Risk Officer, Bank of Ireland, gave evidence in relation to management information systems within the bank generally, and said:

“…there was not enough Management Information System (MIS) functionality, controls, stress testing or scenario evaluation.”48

Evidence provided to the Joint Committee on behalf of NAMA was that deficiencies in management information systems and in the banks’ systems generally had the effect of slowing down the due diligence process.49

Overall, NAMA acquired over 15,000 loans,50 the majority of which involved property exposures. Of the property-related loans transferred, 71% were associated with completed properties, 5% with incomplete developments and 24% with undeveloped land.51 In all, over 75% of the acquired loans were non-performing.52

Over 50% of the property collateral supporting the transferred loans was located in Ireland, with 34.5% of the total being in Dublin. Almost 34% of the property collateral was located in the United Kingdom, with 18.5% of that in London, as illustrated below:

| Dublin | Rest of Ireland | Ireland Total | London | Rest of Britain | Britain Total | Northern Ireland | Rest of World | Total | % | |

| Office | 2,442 | 224 | 2,666 | 1,222 | 878 | 2,100 | 215 | 272 | 5,253 | 16.5% |

| Retail | 1,514 | 1,395 | 2,909 | 279 | 878 | 1,157 | 216 | 145 | 4,427 | 13.9% |

| Other lnvestment (b) | 1,300 | 1,110 | 2,410 | 399 | 826 | 1,225 | 343 | 504 | 4,482 | 14.1% |

| Residential (c) | 2,313 | 1,383 | 3,696 | 375 | 914 | 1,289 | 133 | 156 | 5,274 | 16.6% |

| Hotels | 455 | 479 | 934 | 1,344 | 465 | 1,809 | 12 | 282 | 3,037 | 9.6% |

| Total Completed Properties | 8,024 | 4,591 | 12,615 | 3,619 | 3,961 | 7,580 | 919 | 1,359 | 22,473 | 70.7% |

| Land | 2,417 | 1,757 | 4,174 | 1,356 | 490 | 1,846 | 279 | 158 | 6,457 | 20.3% |

| Development | 521 | 608 | 1,129 | 888 | 446 | 1,334 | 61 | 327 | 2,851 | 9.0% |

| Total Land and Development | 2,938 | 2,365 | 5,303 | 2,244 | 936 | 3,180 | 340 | 485 | 9,308 | 29.3% |

| Total | 10,962 | 6,956 | 17,918 | 5,863 | 4,897 | 10,760 | 1,259 | 1,844 | 31,781 | |

| % | 34.5% | 21.9% | 56.4% | 18.5% | 15.4% | 33.9% | 3.9% | 5.8% | ||

| Source: National Asset Management Agency.Notes:(a) While some loans had not been subject to the full due diligence process by the end of December 2011, the property collateral for the loans had been valued.

(b) other investment property includes industrial property and properties with mixed uses. (c) Includes property to the value of €452 million classified as residential investments. |

||||||||||

Source: C&AG Special Report, Figure 2.953

NAMA valued the acquired loans in two ways. The first method was on a current market value basis and the second was on the basis of a long term economic value.54 All loans acquired were valued as at 30 November 2009, regardless of when they were transferred to NAMA.55 In most cases, the value of the loan was directly related to the value of the underlying collateral.56 This methodology was approved by the European Commission.57

NAMA also took account of the enforceability of the related collateral and the extent to which a Participating Institution had secured its legal right to realise the collateral. In circumstances where this was not done to NAMAR#8217;s satisfaction, the price paid for the loan was reduced accordingly. The reduction in the consideration price paid by NAMA for these loans as a result of unenforceable securities was €477 million initially. A further €334 million was clawed back from the institutions, following further loan-by-loan analysis, for the same reason. The par value of the loans was higher. Brendan McDonagh said: “The value of collateral where we paid nil consideration was €3.5 billion in nominal terms”as a result of unenforceable securities .“58

All loans attaching to an individual borrower were acquired in the same tranche, regardless of which Participating Institution had advanced the loan.59 In total 780 “borrower connections”60 were identified. Given the volume of loans transferred, this was completed in nine tranches.61 NAMA began to acquire loans from 31 March 201062 starting with the largest ten borrowers across the Participating Institutions. By October 2011 the final tranche of loans had been transferred.63

According to the evidence of Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller and Auditor General, “the loan acquisition process was carried out expeditiously by NAMA.”

“Audits and examinations carried out by my Office [C&AG] concluded that the property valuations, legal due diligence and loan valuation processes employed by NAMA were adequate and complied with regulations made by the Minister for Finance in March 2010.”64

NAMA’s method of payment for the transferred loans was as follows:

By December 2011, NAMA had acquired €74.4 billion of loans at a cost of €31.8 billion (43% of par value) from the five Participating Institutions. The breakdown of the transferred loans was as follows:

| Participating banka | Total borrower debt | NAMA payment for loans | Discount | |

| € billion | € billion | € billion | % | |

| AIB | 20.5 | 9.0 | 11.5 | 56 |

| Anglo | 34.4 | 13.4 | 21.0 | 61 |

| Bank of Ireland | 9.9 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 44 |

| Educational Building Society | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 57 |

| Irish Nationwide Building Society | 8.7 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 61 |

| Total | 74.4 | 31.8 | 42.6 | 57 |

| Source: National Asset Management Agency Note: a In 2011, Allied Irish Banks merged with the EBS. Anglo merged with the INBS and was renamed the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation. The loan acquisitions were recorded under the names of each participating bank prior to the mergers. |

||||

Source: Comptroller and Auditor General Special Report, Figure 2.166

With only €31.8 billion being paid for loans of €74.4 billion, the discount of €42.6 billion had to be crystallised by the Participating Institutions. This resulted in the requirement for further recapitalisations throughout 2010 and into 2011 in order that the Participating Institutions could meet their minimum regulatory capital requirements.

NAMA acquired over 15,000 loans from 780 borrower connections. Of these loans, NAMA directly managed 189 borrower connections, with par debt totalling €61 billion and equating to around 85% of the loan values.67 The remaining 586 borrowers were managed directly by the Participating Institutions, who acted as primary servicers.68

NAMA required each of the 780 borrower connections to submit a business plan setting out how they planned to repay their debts. These business plans were reviewed by independent business reviewers appointed by NAMA. On the basis of these business plans and the other means of due diligence employed, NAMA had a full assessment of each borrower’s position by July 2012.69

Once NAMA had completed this borrower assessment (mid-2012), it adopted one of the following loan management strategies in respect of each borrower: full restructuring, partial restructuring, support, consensual disposal or enforcement.

By the end of 2014, however, NAMA had appointed receivers to some or all of the assets of 50% of its debtors.70

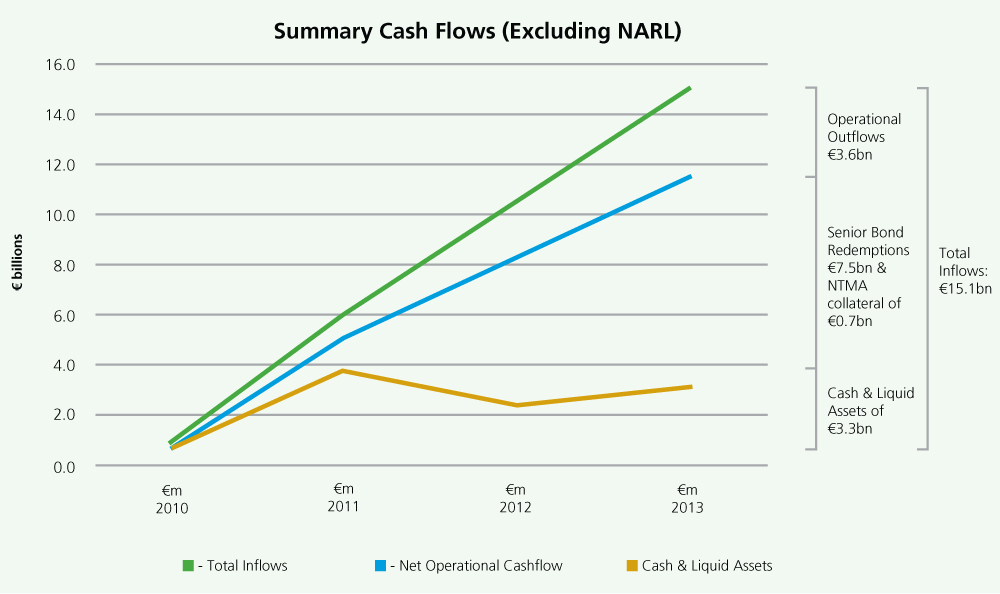

From its establishment through to the end of 2013, NAMA generated total cash inflows of €15.1 billion from asset disposals of €10.9 billion71 and non-disposal income of €3.6 billion72 (mainly rental receipts).

Source: Department of Finance, Figure 1273

The Joint Committee heard evidence in relation to the practice of private equity firms, involving mostly foreign investors, buying up large amounts of property assets, including large portfolio sales by NAMA.

Frank Daly, Chairman, NAMA, stated in his evidence that, while he “would love to see more Irish investors buying Irish assets”, the fact is that overseas investors are needed and “are actually good for the country.”He added that NAMA “have not been fire-selling, and, in fact, we are at the situation now where it is impossible really to forecast when a market will peak or what is the optimum day that you sell your assets.”74

Peter Bacon said: “it [NAMA] has acted more as a debt collection agency than as a property value maximising entity”75 and

“I think there was a decision on foot of the troika recommendation to accelerate NAMA receipts. That certainly would have infringed on any effort to achieve long-term maximisation.”76

The Department of Finance set out the position in an Information Memorandum prepared for the Joint Committee as follows:

“NAMA has committed to ensuring that a pipeline of large portfolios of mainly Irish property assets will be available for sale to the market. In particular, it has committed that packaged transactions of properties with a minimum value of €250m will be offered for sale in each quarter. The aim is to provide certainty about regular asset flows which will provide clarity to potential investors, including international investors and REITs, and thus help to sustain the positive momentum in the market. As with loan sales, large portfolio sales have become an important element in NAMA’s disposal activity.”77

As required by the NAMA Act,78 the Comptroller and Auditor General has examined NAMA on a number of occasions since its establishment. In his written statement to the Joint Committee, Seamus McCarthy, said:

“…overall, the examination found evidence that almost all property disposals reviewed had been sold through an open competitive process, or with testing of disposal prices against market valuation. This provides reasonable assurance that the prices obtained were in line with market prices at the time a property was sold.”79

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Frank Daly said that NAMA was two years ahead of the target which it agreed with the Troika for the repayment of senior debt80 by 2020.81 This statement was supported by Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, in his evidence to the Joint Committee.82

NAMA plans to repay 80% of senior debt by the end of 2016 and 100% of subordinated debt by 2017/2018.83

In an assessment of Ireland’s Bailout Programme, the European Commission stated that:

“By using a centralised asset protection scheme, banks effectively reduced the burden of legacy assets and strengthened their deleveraging and recapitalisation process. NAMA was well placed to manage and liquidate the acquired assets, which were clearly defined, limited in size and relatively easy to sell.”84

According to Alan Ahearne, who was Special Advisor to Brian Lenihan:

“NAMA, serves as an international example of [the] successful management of bad assets…”85

He also gave evidence that:

“…one person’s crystallisation is another person’s facing up to reality. And what … NAMA forced … the banks, the bankers and everybody else to do was face up to the reality of what had happened.”86

In his evidence, David Duffy, Chief Executive Officer of AIB, told the Joint Committee that:

“…the NAMA exercise for us gave us a better understanding on crystallisation of losses, of what the capital deficit was and what necessary actions needed to be taken. So from the narrow view of our execution relationship with NAMA, I would have to say that on balance it was beneficial.”87

Richie Boucher, Group Chief Executive of BOI, also expressed the view that NAMA was a good solution to the problems facing the banks:

“It provided liquidity. It brought everything into the middle. It enabled people with expertise to look at the ... to forget about an individual bank’s situation, how it would work out generally.”88

In the evidence that he provided to the Joint Committee, Brendan McDonagh outlined a number of ways in which NAMA stimulated market activity:

A less positive view was given by Michael O’Flynn of the O’Flynn Group in his statement submitted to the Joint Committee:

“I was told at a very early meeting by the senior [NAMA] executives, “We want disposals. We don’t want plans. We don’t want development. We don’t need any more development.”91

The question of how NAMA performed at an operational level was raised in the testimony of a number of developers who gave evidence to the Joint Committee and whose loans were acquired by NAMA.92 Some developers offered no view on the effectiveness of NAMA based on their dealings with the agency, as they still had relationships to maintain.93

Other developers gave evidence that they have worked well within the NAMA process. For instance, in his evidence to the Joint Committee, Seán Mulryan said that:

“Ballymore has worked with NAMA, co-operated fully and has worked our way through what needed to be done.”94

Joe O’Reilly of Castlethorn Construction and Chartered Land Group expressed a similar view:

“for the past six years, we’ve enjoyed a professional relationship with NAMA and we worked hard to assist the agency to meet its objectives.”95

In his witness statement, Gerard Gannon commented that “…without the establishment of NAMA, we would not be in a position to develop and build much needed family homes for first time buyers…”96

NAMA said that their work required “intensive commitment by us in terms of time and resources involving experienced staff brought together from a wide range of disciplines…”,97 Ann Nolan, Second Secretary, Department of Finance said “…NAMA has proved efficient in dealing with these loans.“98 In their evidence to the Joint Committee, the developers Michael O’Flynn99 and John Ronan100 suggested that NAMA did not have the requisite skills and expertise to effectively manage the scale of acquired loans and assets.

Tom Parlon, Director General, Construction Industry Federation (CIF), provided the following assessment in evidence:

“The CIF believe that NAMA are doing a good job in handling a very difficult role ... They are also one of the few sources of development capital in recent years for the industry, as they are funding the finalisation and the development of some of their assets to realise their full value. Again, this is important and has played a part in the recovery of the construction sector. While we may have expressed strong concerns in the past, I would like to think that the CIF and NAMA have since developed a more co-operative approach. As we have seen the progress being made by NAMA, the industry has come to realise that they are part of the solution.”101

John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA and NAMA Board member, said in evidence:

“I believe that the decision to set up NAMA was the correct one and, based on the NTMA’s engagements with institutional investors and the credit rating agencies I am strongly of the view that its success played a huge role in Ireland later regaining access to the debt capital markets.”102

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Michael Noonan stated his belief that NAMA has played an important and effective role in reactivating the commercial property market in Ireland.103

Seamus McCarthy criticised certain features of NAMA’s reporting of performance.104 He stated that NAMA’s objective of redeeming debt “is not an adequate or relevant performance measure”in terms of obtaining “the best achievable financial return”as specified in the NAMA Act. In that regard, the NAMA Board should have set an “expected or target rate of return.”In its absence, the C&AG has been “unable to conclude on the extent to which NAMA’s performance to date had contributed to obtaining the best achievable financial return.”It was also “difficult to assess the impact of accelerated or delayed cash receipts on NAMA’s profitability.”105

Seamus McCarthy also informed the Joint Committee of his recommendation to the NAMA Board that it should set specific target financial return measures, which would be standard for a recovery unit of a financial institution or investment vehicle, that is to say an overall expected or target rate of return against which to measure overall performance, and a target rate of return on disposals and on property held by debtors and insolvency practitioners.106

The NAMA Board did not accept this recommendation, taking the view that “such target rates of return would not be an appropriate metric for its business, on the basis that they would act as an unnecessary constraint on its flexibility, particularly given the stated objective of the Minister for Finance that NAMA should complete its work of deleveraging the portfolio as soon as possible.“107 Seamus McCarthy concluded that in his opinion, “setting target rates of return is not incompatible with flexible decision making.”108

Separately, the Comptroller and Auditor General expressed criticism of NAMA over its failure to achieve anticipated rental income. In the report, ‘National Asset Management Agency – Management of Loans’, it was commented:

“… For six borrowers, 2011 rental income was around 26% less than that projected at acquisition and, for this sample, only €8 million out of €10.5 million subsequently projected in business plans had been realised.

The difference between rental income anticipated at loan valuation and net rental income received during 2011 on the cases sampled was mainly due to property management costs that were not provided for in the loan valuations which were conducted in line with industry norms for immediate sales.”109

The one-year time-lag between Peter Bacon’s proposal for a NAMA-type solution and the transfer of the first loans caused considerable uncertainty and difficulty for some developers, as they were caught in a ‘no man’s land’ between their financial institutions and a NAMA not yet formally established.

For some developers, the establishment of NAMA bought time. Sean Mulryan told us:

“So while we knew we were in a good position to withstand the crisis, what Ballymore needed was time and a mechanism to get through the period between the collapse and the recovery. NAMA provided the means for Ballymore to do that.”110

Having regard to the scale, complexities and risks involved, it was essential that the enabling legislation and the ultimate structure would be especially robust.

NAMA acquired 90% of all identified eligible loans from the five Participating Institutions above a threshold of €20 million, both performing and non-performing, and including unencumbered assets. The number of loans involved was in excess of 15,000, over 75% of which were non-performing. Over 50% of the transferred loans related to properties in Ireland and over 30% in England.

While the Participating Institutions worked to transfer the loans across to NAMA, there were difficulties in providing the information sought for due diligence purposes. The reason for this was suggested to have emanated from weaknesses in management information systems, stress tests, credit management information and scenario evaluation.111

NAMA directly managed 189 borrower connections, with par debt totalling €61 billion, equating to around 85% of the loans transferred to it (by value). The remaining 586 borrowers were managed by the Participating Institutions themselves who acted as primary servicers.

While some developers criticised NAMA’s skillsets, this was disputed by other witnesses. Similarly, there were both positive and negative views on the developers’ relationships with NAMA.

The review by the Joint Committee of NAMA’s effectiveness is limited by the fact that we are only in a position to examine events up to December 2013. Furthermore, it will not be possible to fully assess NAMA’s performance and effectiveness until an evaluation based on medium-term property price movements can be carried out.

Chapter 9 Footnotes

1. Memo for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-001/002. Note: The Bacon Report was considered by the Department of Finance, Central Bank, Financial Regulator, NTMA and Merrill Lynch, DOF03553-004.

2. Bacon Evaluation of Options for Resolving Property Loan Impairments and Associated Capital Adequacy of Irish Credit Institutions 2009, PUB00067-004.

3. Bacon Evaluation of Options for Resolving Property Loan Impairments and Associated Capital Adequacy of Irish Credit Institutions 2009, PUB00067.

4. Memo for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-002.

5. Memo for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-002/003.

6. Memo for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-003.

7. Consensus - in favour of asset management over risk insurance solution – was reached by Department of Finance, Central Bank, Financial Regulator, NTMA and Merrill Lynch, Memo for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-004.

8. Peter Bacon, Economist, transcript, PUB00334-014.

9. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-024.

10. Peter Bacon, Economist, transcript, PUB00334-031.

11. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-024.

12. Memorandum for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-003.

13. Memorandum for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-004. (See Glossary of Terms for definition of SME).

14. Financial Statement of former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, 7 April 2009, PUB00386-012.

15. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, statement, PGA00001-012.

16. C&AG Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets, October 2010, NAMA00011-027.

17. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, statement, PGA00001-012/013.

18. Memorandum for Government, March 2009, DOF03553-022.

19. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, statement, PGA00001-012/013.

20. C&AG Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets, October 2010, NAMA00011-009. See also European Commission press release: State aid: Commission approves Irish impaired asset relief scheme, 26th February 2010 - http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-10-198_en.htm.

21. Section 67 of NAMA Act 2009, DOF06753-055.

22. Section 69 of NAMA Act 2009, DOF06753-057/058.

23. Part 5 - Valuation Methodology, NAMA Act 2009, DOF06753-060 to 065.

24. Section 99 of NAMA Act 2009, DOF06753-078.

25. Section 10 of NAMA Act 2009, DOF06753-025.

26. Sean Mulryan, Developer, Ballymore Group, statement, SMU00001-021 and transcript, INQ00119-024/025.

27. Sean Mulryan, Developer, Ballymore Group, transcript, INQ00119-025.

28. Sean Mulryan, Developer, Ballymore Group, transcript, INQ00119-024.

29. Michael O’Flynn, Developer, O’Flynn Group, transcript, INQ00121-025.

30. Joe O’Reilly, Developer, Castlethorn Group, transcript, INQ00126-027.

31. Gerard Gannon, Developer, Gannon Homes, statement, GGA00001-009.

32. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-133.

33. According to C&AG final discount was 57% – Brendan McDonagh, CEO, NAMA refers to the final discount as 58%.

34. C&AG Progress Report 2010-2012, NAMA00010-009.

35. NAMA Act 2009, section 62, DOF06753-052.

36. NAMA Act 2009, section 67, DOF06753-055.

37. Associated borrowers as defined in section 70 of the NAMA Act 2009, DOF06753-058.

38. Non loan contracts such as an interest rate derivative that hedges interest rate exposure or options.

39. C&AG Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets, October 2010, NAMA00011-032.

40. Sean Mulryan, Developer, Ballymore Group, statement, SMU00001-021.

41. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript PUB00351-013. Note, this is also supported the C&AG Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets, October 2010, NAMA00011-031.

42. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, statement, BCO00002-018; European Commission report, ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Ireland’, February 2011, DOF05089-017 and C&AG’s ‘Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets’, October 2010, NAMA00011-034.

43. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, statement, BCO00002-019; NAMA Annual Report and Financial Statement 2011, NAMA 00027-020.

44. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-009. C&AG ‘Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012’, April 2014, NAMA00010-019.

45. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-027.

46. Brendan McDonagh, CEO, NAMA, transcript, PUB00331-065 and Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-009.

47. Kieran Bennett, former Risk Officer, AIB, statement, KBE00001-004. Dermot Gleeson, former Chairman, AIB, also spoke of the MIS not being able to produce the information required by NAMA on interest roll-up, transcript, INQ00123-065/066.

48. Ronan Murphy, former Chief Governance Risk Officer, BOI, statement, RMY00001-012.

49. NAMA’s written response to 10 specific questions by the Joint Committee, 11 March 2015, NAMA00097-007.

50. C&AG ‘Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012’, April 2014, NAMA00010-009.

51. C&AG ‘Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012’, April 2014, NAMA00010-024.

52. Brendan McDonagh, CEO, NAMA, transcript, PUB00331-046. NAMA00104-001

53. C&AG Special Report, Management of Loans, February 2012, NAMA00012-034.

54. C&AG ‘Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012’, April 2014, NAMA00010-020.

55. C&AG ‘Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012’, April 2014, NAMA00010-020.

56. C&AG ‘Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012’, April 2014, NAMA00010-021.

57. C&AG ‘Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012’, April 2014, NAMA Special Submission No. 2, NAMA00010-019.

58. Brendan McDonagh, CEO, NAMA, transcript, PUB00331-059.

59. C&AG Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets, October 2010, NAMA00011-031.

60. NAMA Section 227 Review by Department of Finance, July 2014, NAMA00103-013.

61. C&AG Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012, April 2014, NAMA00010-020.

62. C&AG Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets, October 2010, NAMA00011-027.

63. NAMA section 227 Review, July 2014, NAMA00103-020.

64. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement SMC00004-009.

65. C&AG Special Report, Acquisition of Bank Assets, October 2010, NAMA00011-024.

66. C&AG Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012, April 2014, NAMA00010-021.

67. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-010.

68. The primary servicer role includes maintaining and updating borrowers’ loan records, processing receipts from borrowers and transferring cash received to NAMA, and reporting all transactions to the master servicer. NAMA00010-041.

69. C&AG Special Report, Progress Report 2010 – 2012, April 2014, NAMA00010-042.

70. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-010.

71. NAMA Annual Report and Financial Statement 2013, NAMA00028-014.

72. NAMA Annual Report and Financial Statement 2013, NAMA00028-035.

73. NAMA Section 227 Review by Department of Finance, July 2014, NAMA00103-029.

74. Frank Daly, Chairman, NAMA, transcript, PUB0331-043.

75. Peter Bacon, Economist, transcript, PUB00334-15.

76. Peter Bacon, Economist, transcript, PUB00334-21.

77. Department of Finance Submission to the Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015, DOF07852-029.

78. Section 58 of the NAMA Act, 2009 provides for NAMA’s Accountability to the Committee of Public Accounts. DOF06753-050.

79. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-011.

80. Senior debt is debt that takes priority over other unsecured debt owed by the issuer such as subordinated debt. See Glossary of Terms for more detail.

81. Frank Daly, Chairman, NAMA, transcript, PUB00331-016/018/019.

82. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, statement, MNO00003-021.

83. Frank Daly, Chairman, NAMA, transcript, PUB00331-019 and Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, statement, MNO00003-021.

84. Ex post Evaluation of the Economic Adjustment Programme Ireland, 2010-2013, PUB00356-055.

85. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-003. Alan Ahearne commented that Spain and Slovenia copied the NAMA model almost verbatim, transcript, INQ00094-029.

86. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-010.

87. David Duffy, Chief Executive, AIB, transcript INQ00134-009.

88. Richie Boucher, Group CEO, BOI, transcript INQ00085-023/024.

89. See Glossary of Terms.

90. Brendan McDonagh, CEO, NAMA, transcript PUB00331-006.

91. Michael O’Flynn, Developer, O’Flynn Group, statement MOF00006-006/007 and -013 to 022; John Ronan, Developer, Treasury Holdings & Ronan Group Real Estate, statement, JRO00002-017 to 028.

92. Derek Quinlan, Sean Mulryan, Michael O’Flynn, Joe O’Reilly, John Ronan, Gerard Gannon, Gerard Barrett, Peter Cosgrave, Bernard McNamara.

93. Gerard Barrett, Group Chairman and Managing Director, Edward Holdings, statement GBA00001-022; Derek Quinlan, Financier, Quinlan Private, transcript, INQ00092-023.

94. Sean Mulryan, Developer, Ballymore Group, transcript, INQ00119-005.

95. Joe O’Reilly, Developer, Chartered Land and Castlethorn, transcript, INQ00126-005.

96. Gerard Gannon, Developer, Gannon Homes, statement, GGA00001-010.

97. Brendan McDonagh, CEO, NAMA, transcript, PUB00331-006

98. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-003.

99. Michael O’Flynn, Developer, O’Flynn Group, statement, MOF00006-016.

100. John Ronan, Developer, Treasury Holdings & Ronan Group Real Estate, statement, JRO00002-027.

101. Tom Parlon, Director General, CIF, transcript, INQ00064-008.

102. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-004.

103. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, statement, MNO00003-021.

104. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-013.

105. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-013.

106. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-013.

107. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-013.

108. Seamus McCarthy, Comptroller & Auditor General, statement, SMC00004-013.

109. C&AG Special Report, NAMA – Management of Loans, February 2012, NAMA00012-011.

110. Sean Mulryan, Founder, Chairman & Group Chief Executive of the Ballymore Group, transcript, INQ00119-005.

111. Submission to the Banking Inquiry: Nama Questions 11.03.15.pdf, NAMA00097-006/007