Back to Chapter 9: Establishment, Operation and Effectiveness of NAMA

On 27 November 2010, the Irish Government formally applied to enter a programme with the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF (also known as the Troika). This followed several weeks of informal discussions and one week of formal talks between the Government and the Troika. Entering into the Troika Programme (or “bailout” as it was more colloquially described by some witnesses) came as something of a surprise to the general public.

The Joint Committee wanted to understand why the Irish Government entered into the Troika Programme, the clear sequence of events leading to the Government decision as well as the implementation of the programme until Ireland’s exit.

The Joint Committee also sought to understand:

The question of burden-sharing, which arose in the course of the Troika Programme negotiations, is addressed in Chapter 11.

It should be noted that the ECB did not cooperate with the Banking Inquiry. While the ECB is legally accountable to the European Parliament, the Joint Committee are not aware of anything preventing the ECB from participating in a parliamentary inquiry. The Joint Committee’s efforts to engage with the ECB are set out in Volume 2 of this report.

The notion or possibility that Ireland might need external assistance at some point in managing the economic crisis was first considered by the relevant parties in September 2008. A request for “very preliminary and informal work on how a country enters an IMF programme” was requested by the then Assistant Secretary, Department of Finance, Kevin Cardiff. He said:

“Well, at that point, we might have looked for some ... we might have had to look for some external support. Certainly, it wasn’t the plan ... it was nobody’s intention but the first time I asked for some very, very preliminary and informal work on, you know, how one actually gets an IMF programme, was in September 2008, and at that point, I was thinking, you know, there was no work done on it. I just asked a colleague to make a discreet inquiry as to how you get into these things, if you do need them, just as a precaution because things were very bad from then.”1

In 2009 and again in 2010, it was communicated to the Government that IMF assistance was available, if needed. Former Deputy Director, IMF, Ajai Chopra, stated in evidence that the IMF had been in formal contact with the Irish authorities on at least two different occasions, in 2009 and 2010. However, he said this should not be interpreted as giving the impression that the IMF “were out here badgering the authorities to get into a programme…”2

If the IMF was not “badgering” the Government, neither were the Irish authorities engaging with the suggestion. As Kevin Cardiff said:

“Then in 2009, I believe there were hints in Washington, possibly also in Dublin, that, you know, IMF would be available if we wanted them. At that point, the Minister gave a pretty firm instruction to me and to others that we were not engaging with that suggestion but in part because ... remember, a bank crisis means you have to fill gaps in liquidity and gaps in bank liquidity are enormous. Capital is a lesser problem; liquidity is an enormous gap. And you really need the firepower of a central bank to do that. Now, in 2009 and into 2010, we had no problem getting funds for the Government, which is what the IMF provides.”3

However, the consideration of entering a programme was not just an economic one; being “bailed out” had broader implications for the country, as former Chief Executive, NTMA, Michael Somers captured in his testimony before the Joint Committee:

“I never thought that it would happen. I mean, one of the nightmares for us for many years – because I was responsible for our end for many years – was the IMF. I mean, that was the thing. Actually … because we would be writing memos to Government telling them to cut back on their expenditure. That was the bogeyman that we held up, “Listen, if you don’t behave yourselves and get your finances under control, the next thing is we’ll have the IMF in here running the show for us.” So, for me, I felt it was the ultimate humiliation actually for us, as a country, to have the IMF come in to run the show for us.”4

Ajai Chopra told the Joint Committee of the “stigma” associated with entering an IMF programme:

“…the right time for a country to enter into a programme is when it’s vulnerable but not in a full-blown crisis. Now, within that, there’s a continuum. At one end of the continuum, you have a situation where a country can ask for help at the very first sign of some trouble, or it could wait, and the other end of the continuum would be that it cannot pay next week’s wages, pensions and debt service. So within that, there’s a number of other possibilities. Now, it’s most unusual for a country to come right at the beginning, at the first sign of trouble, because there is an enormous amount of stigma. ... It’s well known that there’s stigma about entering into an IMF programme. And also there’s always the hope that you can ride out the troubles. But it’s equally disadvantageous to come at the very end, and Ireland did not do that.”5

Possibly the most active suggestion on the part of the IMF was that the Irish authorities might consider a programme of assistance came in the second quarter of 2010. Former Governor of the Central Bank, Patrick Honohan, spoke about this in his evidence to the Joint Committee:

“So I got a call from Ashoka Mody, who we know was subsequently in here and he ... out of the blue he said “You know we’re coming, we’re coming later in the month for the Article 4.” Yes I know. “And we’re just wondering would you think Ireland would be interested in one of these precautionary programmes?” And I knew that ... there are a number of ... two particular precautionary programmes, I’m not sure which one he was talking about. One of them was for countries that were really considered very well run, very well managed but just vulnerable to pressure from the market. Mexico I think qualified for one of these and may have taken one of these ones.”6

The Central Bank was not advocating that Ireland pursue a precautionary line from the IMF at this stage. Patrick Honohan said:

“And I thought this might be quite good, we’d get a ... we’d get a seal of approval, potential access to money and it might be good. But I didn’t think it as a wonderful thing which would have really been, you know, let’s go for that, because if I had, we would have been advocating it as well.”7

Nevertheless, Patrick Honohan said that he thought the idea worth considering:

“In six months’ time, we had a real line [bailout programme]. So it ... okay, the step I took was to tell Mody, “I think you should raise it with the Government because I think it’s a good idea.” He raised it, I presume ... well, I know, because they came back to me and it was shot down. But I think it was ... it’s more that it reflects, first of all, a sense that the IMF team thought we were being well-run, because they didn’t give these things to countries that were not being well-run, and that there was that sense of concern. We weren’t there blithely going along saying, “Everything’s fine here.” We were aware of the concern.”8

Developments in Greece around this time may present some context. In April 2010, Greece was in discussions to enter a Troika Programme. Former Taoiseach Brian Cowen, told us that international perceptions of Ireland “were not helped” by the Greek situation whereby: “Greek Government bond yields [had] soared to over 15% … its Government could not borrow any further [and] it applied for external assistance in April 2010…”9

The Greek request for assistance prompted the suggestion by Patrick Honohan of the Central Bank that Ireland “could” be next to request assistance. As he told the Joint Committee, referring to an interaction he had with the then Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan:

“[Brian Lenihan:] I have to ask you your advice on whether we should go ahead and support and put Irish money into this Greek programme that’s being envisaged.” So I think it was 10 April and I said, “I think you should,’’ and he said, “Yes, I have the same view because you know we are going to make money on it because we are borrowing at this and we are going to get this amount of money’’, and I said, “That’s not the reason,’’ I said, “The reason is we could be next.’’ “Oh no,’’ he said, “No, no, I’ve been talking to the people in Brussels and they say Portugal is next.”10

It is important to underline the seriousness of the situation facing the Irish Government through 2010. As Brian Cowen said:

“But the point I’m making to you is that, regardless of what the IMF were saying, you know, we were coming to a position in relation to our own situation to say that we would prepare a four-year plan anyway, regardless if there was never a European dimension to it.”11

Sovereign deficits were climbing in Europe as the crisis continued and the possibility of a Eurozone country exiting the Euro, either in tandem with or because of a default on Sovereign debts, was being discussed openly.

Kevin Cardiff spoke about the work of a small group focusing on Ireland’s potential exit from the Euro:

“There was certainly work done on what would happen if we found ourselves unceremoniously shown the door or if that became the only option” before continuing: “there was a number of contingency papers drafted but the work was kept to an absolute very small group of people,”12 and “the policy was clear… it was ... the Minister’s view that the Government’s view was clear. We are not working towards exiting the euro; we were working towards staying in it. That was always clear; there was never a debate.”13

As already set out in Chapter 7, the Government decided in September 2008 to guarantee all liabilities, both existing and new, for each of the Covered Institutions (the State Guarantee). Under the Credit Institutions Financial Support Act 2008 (CIFS Act 2008) all deposits, senior debt, covered bonds and dated subordinated bonds of the Participating Institutions were covered under this blanket guarantee scheme up to 29 September 2010. The only major exclusion was perpetual bonds.14

Within the two year period of the State Guarantee, the Irish Covered Institutions were able to refinance liquidity requirements as they were supported by the State’s Guarantee and had access to monetary authorities. Initially the CIFS scheme guaranteed €375.25 billion, the additional €77.41 billion was already covered by the Deposit Guarantee Scheme.15 The European Commission in its ex post evaluation of Ireland’s bailout programme included the following assessment of the linkage that had become established between bank debt and national debt:

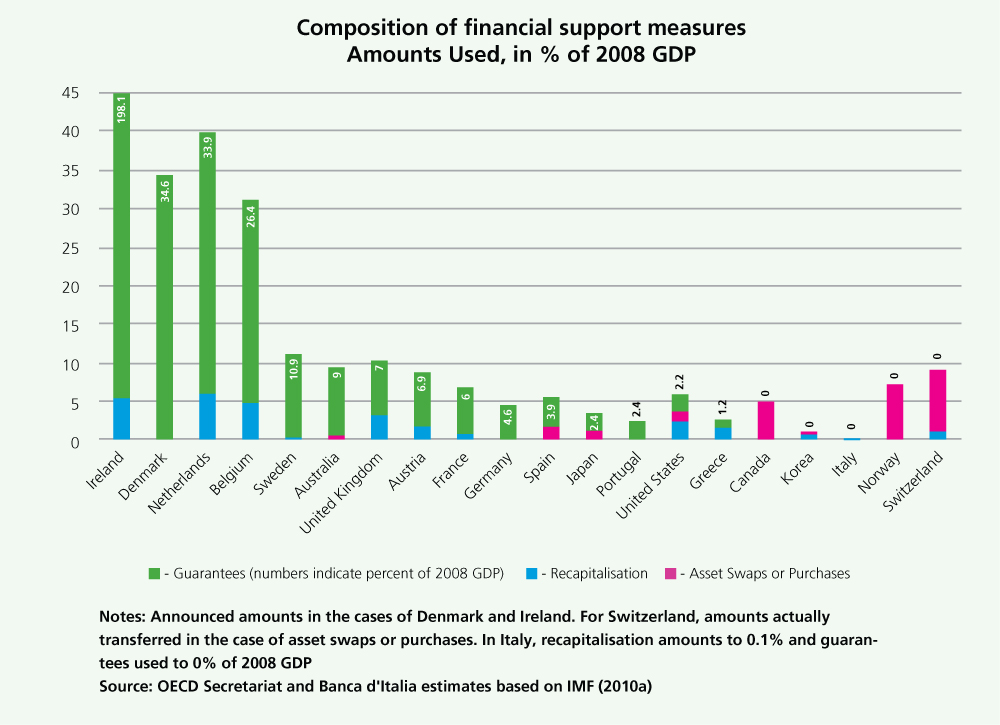

“In practice in September 2008, the authorities issued a two-year guarantee on existing banks’ liabilities (Credit Institutions Financial Support Scheme - CIFS) amounting to €375bn (200% of GDP), in order to overcome banks’ funding problems and address potential capital shortfalls. As a result, the solvency of the Irish sovereign and that of the banking system became directly intertwined. This eventually turned the banking crisis into a sovereign debt crisis…”16

Source: Extract from OECD journal financial market trends volume 2010 Figure 7.1

As illustrated above, Ireland had by far the highest level of guaranteed financial support provided in % of GDP in 2008.17

This increasing volume of bonds, maturing in September 2010, created a potential “ funding cliff ” in the eyes of the authorities.

Author and journalist, Simon Carswell said that, because of the nature of the State Guarantee, “there was always going to be a funding cliff at a particular point”.18

Patrick Honohan told us: “if it had have been a one-year guarantee, the cliff would have just come earlier” .19

In early 2010, the Central Bank, through the Prudential Capital Adequacy Review (PCAR) process, identified an additional need for approximately €10.9 billion in capital requirements for the Covered Institutions. As NAMA continued its work in transferring loans from the Covered Institutions and the extent of the discounts became clear, capital requirements for some of the banks increased (see Chapter 8).

Between October 2008 and May 2010, the Covered Institutions issued 174 guaranteed bonds, the total value of which amounted to €61.2 billion or, on average, €400 million per issue, as per the following table.

| Country | Total issuance (billion euro) | Number of issuers | Number of bonds issued | Average size of each bond (billion euro) | Average maturity at issuance (months) | Percentage of available guarantees |

| Australia | 109,5 | 20 | 311 | 0,4 | 40 | (3) |

| Austria | 20,0 | 6 | 21 | 1,0 | 38 | 27 |

| Belgium | 4,0 | 1 | 4 | 1,0 | 23 | 21 (2) |

| Denmark | 32.2 | 40 | 177 | 0,2 | 28 | (3) |

| France | 127,6 | 2 | 77 | 1,7 | 33 | 48 |

| Germany | 184,1 | 11 | 47 | 3,9 | 27 | 46 |

| Greece | 8,5 | 3 | 6 | 1,4 | 33 | 30 |

| Ireland | 61,2 | 10 | 174 | 0,4 | 30 | 100 (2) |

| Luxemburg | 0,7 | 1 | 2 | 0,3 | 21 | 16 |

| Netherlands | 47,1 | 6 | 38 | 1,2 | 46 | 24 |

| New Zealand | 6,0 | 7 | 22 | 0,3 | 40 | (3) |

| Portugal | 4,4 | 5 | 5 | 0,9 | 36 | 22 |

| South Korea | 0,9 | 1 | 2 | 0,5 | 33 | 1 |

| Spain | 40,3 | 34 | 95 | 0,4 | 37 | 40 |

| Sweden | 18,3 | 5 | 71 | 0,3 | 40 | 14 |

| United Kingdom | 147,3 | 14 | 165 | 0,9 | 30 | 54 |

| United States | 248,2 | 42 | 191 | 1,3 | 33 | 14 |

| (1) Source for committed amounts: European Commission. (2) Authorised program size not available. Source: Estimates by OECD Secretariat and Banca d'ltalia based on Bloomberg and BIS. |

||||||

Source: Extract from OECD journal financial market trends volume 2010, Table 320

Special Advisor to the then Minister for Finance Brian Lenihan, Alan Ahearne, explained that the effect of these developments was that, by spring 2010, Irish banks were receiving inflows of “half a billion a week” and “so that [funding] at least had stabilised”.21 Despite that, he said that:

“It was clear they wouldn’t raise enough private funding to get over the cliff, and therefore the Eurosystem, the ECB and the Irish Central Bank would have to help out temporarily, but if they had, in the months that then followed, they would continue to issue bonds and raise funds, and they would’ve been able to repay that”.22

As this situation was developing, the bank funding cliff was materialising for the Covered Institutions. The authorities were well aware of this, as Patrick Honohan said:

“So, first of all, the funding cliff did not become evident in May 2010, the funding cliff was evident ... certainly from the time that I started in September 2009. I constantly asked, as I said earlier ... they kept on saying “Well, there’s going to be these maturities of debt in this week and that week.” I asked “When is the worst month?” and they said “The worst month. The next month is always the worst month, but after that it’s September 2010”. And that’s because, after the guarantee, as I understand it, the banks issued bonds and deposits to mature at or before ... shortly before the guarantee. So it was well known this was going to be a cliff; so we’re going to have to do something to build sufficient confidence in the banking system that the depositors, when they get to the end of September, will say, “Oh yeah we’ll just roll that over for another year. That’s, of course, what we failed to do.”23

When Dermot McCarthy, former Secretary General in the Department of the Taoiseach, was asked if, in his opinion, the duration of the State Guarantee created the conditions for the funding cliff that precipitated the bailout, he stated:

“It may have done, Chairman, in this sense: that clearly a time-limited guarantee was always going to create an exit issue. Now, that was anticipated quite early on and my recollection is that, in early 2009, the Minister sought the approval of the Government to seek agreement for a variant on the guarantee scheme to allow the issue of longer-term bonds and there was then a new scheme, the eligible liabilities guarantee scheme, which was approved by the Commission much later in 2009. Then there was the question of extending the period from September 2010 and, from recollection, I think it was June, or mid-year, that approval was received. So, there were attempts to avert that cliff situation emerging but, I think, in practice, it did contribute to the timing, the build-up of those liquidity pressures in the latter part of 2010”.24

Whilst the Irish authorities were aware of and preparing for the funding cliff, it is less clear to what extent the ECB was being kept informed. Patrick Honohan told the Joint Committee about his efforts, in summer 2010, to alert the ECB to the forthcoming bank funding cliff:

“I wrote at the end of July and I fully expected then in August ... early meeting to be pulled aside and you know, “What do you mean saying this?”, this is, you know ... dead silence, which I took as good news, they must have figured this out themselves, this is no surprise in my letter. So I wrote another letter in ... in August. I shouldn’t really be going into a lot of detail about communications within the Eurosystem, to some extent I’m writing on behalf of Ireland of course which is what allows me to talk about them at all. So I ... obviously I provided full information at the end of August again. Then of course I did get the response, the concern and the anxiety was starting to build there.”25

Patrick Honohan noted a “change in attitude” on the part of the ECB at this point:

“But it was really the change in attitude in August of 2010 and September, and, in September, we were absolutely in the centre of attention. And I remember one senior colleague saying, “I’m afraid that Greece is Europe’s Bear Stearns but Ireland will be Europe’s Lehman’s.” That was in September 2010.”26

Former President of ECB, Jean-Claude Trichet gave a retrospective view on the period:

“…By late 2010, the imminent expiry of the original two-year guarantee - which in the meantime had been partially superseded by the so-called eligible liabilities guarantee, ELG, had left the Irish authorities in an extremely difficult situation. The so-called CIFS cliff, the wave of debt maturing in September 2010 issued under the guarantee confirmed Ireland’s loss of access to sovereign markets. Combined with other factors, such as the ever-worsening fiscal situation, the Irish Government was confronted with no alternative but to ask for official support…”27

Meanwhile, Kevin Cardiff told us that, in summer 2010, the Government “started the process with the European Commission of getting renewals in place for the end of the guarantee”.28 This was approved “around 21-22 September 2010.”29

Arising from the introduction of the Eligible Liabilities Guarantee Scheme, the Irish Covered Institutions were able to access funding to repay the bonds maturing after the expiry of the original State Guarantee at the end of September 2010.

As of September 2010, the ECB was a significant creditor to Covered Institutions through Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) and the Irish Sovereign’s credit ratings were being adversely impacted by increasing losses in the Covered Institutions, including concerns over asset quality, over-exposure to property and property-related transactions and falling asset values.

Investors saw a link between the perceived health of the Covered Institutions and the cost of Government debt. John Corrigan, CEO of NTMA commented that, around September 2010, “…The extent of the additional capital requirements and, in particular, the huge loss announced by Anglo during this period were major factors in Ireland subsequently having to withdraw from the bond markets…”30

The ECB was becoming more concerned about the reliance of the Irish Covered Institutions on ELA, which was collaterised with securities issued or guaranteed by the Irish Government, and at a time when the Government was seeing its own borrowing costs rising to a point where it may not have been possible to borrow any more, with Irish bond yields “touching 7%” .31 Although ELA was for banks, because the State stood behind the banks, ELA could effectively be considered as a liability of the State.

Towards the end of September 2010, the Government withdrew from the Sovereign bond market, announcing “that it would not borrow any further funds for a period, and in the meanwhile would draw down on the large cash pile it then held, precisely for this type of eventuality…”32

The anticipation of further banking costs post-September 2010, combined with a question mark over whether the Sovereign could continue to service such large debts while also managing the ever-widening negative fiscal position, meant that interest rates for Irish Government debt had effectively risen to a level that was unsustainable.

Kevin Cardiff said:

“There is no particular ‘magic number’ level at which interest rates become unsustainably high for a sovereign borrower: it depends on all sorts of factors. But some commentators had decided that a 7% yield might be seen as a ‘cut-off’ point, after which a country should be seen as being in trouble. Irish yields were heading for that point…”33

In the view of Simon Carswell: “ELA was the trigger for the bailout” because “the European Central Bank’s view was that it had taken on a credit risk with Ireland and it was exposed to Ireland because the State had stood behind the banks”.34 Patrick Honohan made a similar point when he said that the “rapid increase in ELA” in September 2010 made observers believe a programme of support would be necessary.35

Whether the “funding cliff” was a pivotal issue was questioned by Kevin Cardiff when he said that “frankly, the funding cliff was a small number of tens of billions” and that “in bank liquidity terms, on a balance sheet of €400 billion or €500 billion, it’s a residual piece” .36

Pressure on the Government from the ECB was now growing, as illustrated by evidence given to us. Kevin Cardiff said:

“During September 2010, Brian Lenihan took a call from Jean-Claude Trichet, president of the ECB. Trichet was demanding to know what Ireland was doing about the continuing pressure on the fiscal and banking position…Trichet demanded that the European Commission be allowed to come to Ireland to examine the situation. ...”37

From this point on, a series of meetings were held in Dublin and Brussels from the end of September, through October and November, to consider how the Irish Government might resolve its continuing fiscal and banking difficulties. This prompts us to ask whether some form of programme was already imminent at this point – and whether there was an ECB bias in favour of Ireland entering a Troika Programme?

Kevin Cardiff, in his written statement, described a meeting on 22 September 2010 in Brussels, where a team led by Minister Brian Lenihan held a confidential discussion with EU officials:

“…at this stage no one present was actively advocating a bailout – in fact most of those present wanted to avoid it. Certainly, after spending some time with him alone, Lenihan told me that Commissioner Rehn thought it was still on balance more likely than not that a bailout could be avoided – though it had to be considered a possibility – even, according to Lenihan, suggesting that the Portuguese were a more likely candidate for bail-out at that stage than was Ireland. But Marco Buti, who reported directly to Rehn, told me separately that it was his personal view that a bailout would probably on balance be required. He was not advocating it, at this stage, merely giving an opinion on the likely turn of events However, while neither the European nor the Irish political systems were yet prepared for a bailout, it could certainly be seen as starting to feature in discussions as at least a “Plan B”, from then on. For Ireland, however, it was considered too soon to contemplate.”38

When this was put to Marco Buti, he said:

“I think at the time, the ... after having had the Greek programme, with the mounting tensions and the increase ... rapid increase in the spreads on the Irish Government bonds, I think it was not only ... it was not essentially myself; I think that it was quite, you know, a widespread view that should the crisis not abate by itself - it didn’t look like it at the time - that Ireland could be a potential candidate for an assistance programme…“39

In October 2010, the ECB wrote to the Government expressing its concern regarding the “extraordinarily large provision of liquidity by the Eurosystem to the Irish banks.”40

The ECB suggested that ELA provisions might only be able to continue with “progress in economic policy adjustment, enhancing financial sector capital and bank restructuring”.41

The Government was in the process of formulating a four year National Recovery Plan 2011-201442 to manage the fiscal situation and budget shortfall. This work had commenced in the summer of 2010.43

By end-2009, General Government Gross Debt had reached 66% of GDP, reflecting the large deficits recorded in the intervening period, amongst other factors.44 It was estimated that the ratio would be 95% of GDP at end 2010.45 The main reason for this very large increase in 2010 was the capital support of €30.9 billion provided to a number of Covered Institutions within the banking sector in 2010, which was classified within the General Government Debt.46 (See also Chapter 8). The fiscal situation and budget shortfall demanded urgent adjustment and this was formulated into a National Recovery Plan 2011-2014.47

In evidence from Alan Ahearne, the Joint Committee was told that Brian Lenihan had suggested to EU officials that, together with this plan, Ireland might enter a precautionary programme with quarterly surveillance until mid-to-late 2011, when Sovereign cash reserves would have run-out. It was hoped that if access to the market was not available then, the Government would enter a full programme. Alan Ahearne said the Minister was looking for time. His evidence is interesting in this respect, when considering possible alternatives to the full Troika Programme that was agreed in November 2011:

“Ireland was under pressure in sovereign ... in the markets. The national recovery plan would have been part of it, so what he wanted to do was get the national recovery plan out, publish it. He wanted the ECB to say that ... because the banks were separately under stress on their funding, he wanted the ECB to say publicly that they stood behind the Irish banks and provide liquidity. By the way, the ECB were never asked to give capital to the Irish banks. It’s not that they were asked to pay for a single cent, they were being asked to give funding but they were repaid all the funding. But he wanted them to say that they would stand behind him. And then he was willing to enter some sort of precautionary programme and what he had in mind is they could ... I mean, he said they could do quarterly surveillance if they wanted but the Irish State had enough ... the sovereign had enough money to keep going to the middle of 2011. So he said “Look, let’s use that money. If the markets haven’t improved, we can run down that money. We’ve just given ourselves time, given everybody time [the Irish State] given the Europeans time.” Because they were in turmoil over what was going on - this was, remember, the start of the EU area crisis - maybe get some money to keep the State going until the end of 2011 and at that stage if Ireland still did not have access to the markets, they had pulled out at this stage, then we’d go for a full-blown programme, but he wanted some time.”48

In his evidence, John Corrigan referred to a statement made at an EU summit in Deauville, Northern France in October 2010:

“The tone of eurozone sovereign bond markets was severely damaged in October 2010 when, at an EU summit in Deauville, Chancellor Merkel and President Sarkozy said that holders of eurozone sovereign debt should be forced to take losses or haircuts as part of any debt restructuring.”49

This statement on 18 October 2010, referred to in evidence by John Corrigan, became known as the “Deauville Declaration” caused “further market jitters and the damage was done and bond yields jumped further” in the words of Brian Cowen.50

On 25 October 2010, Brian Lenihan led a team of officials to Brussels to meet with the European Commission and ECB. As Kevin Cardiff described it to the Joint Committee, “The first part of the meeting was with the European Commission only – maintaining for a brief moment the fiction that the ECB was present to deal mostly with banking matters.”51

The Irish party at the meeting presented their projections for 2011. While there was broad agreement on many of the points presented, there were a number of difficulties:

“…But even allowing for that difference there was some real space between us on what the 2011 adjustment should be. Lenihan, in the course of the discussion had already drifted towards his limit of €5bn and Rehn had come down to €6bn, but there the room for manoeuvre seemed to stop…”52

Kevin Cardiff also said in evidence:

“… The differences in macro-economic assumptions led to a technical difference between us in reaching the target of a 3% deficit by 2014. (The IMF already believed this was an unrealistic target, but the Commission was not ready for that discussion at that stage).”53

Jürgen Stark and Klaus Masuch of the ECB joined the discussion for the “banking” part of the meeting and, in his evidence, Kevin Cardiff summarised what they said at that meeting as follows:

“…The ECB was owed €116bn by Irish banks and the situation was getting worse – this was not sustainable. ‘Emergency’, Stark noted, was supposed to mean short-term and there was unease in the ECB about the ongoing nature of this lending, which had to be re-approved every two weeks. There was therefore an urgent need to consider a restructuring plan for the banking system, which should be part of an “overarching programme” also involving fiscal adjustments…”54

A meeting of the G20 Nations took place in Seoul, South Korea on 11-12 November 2010.55 At this meeting, the Irish economic situation was discussed and, following these discussions, it would appear that the possibility of a precautionary programme receded. Dermot McCarthy testified:

“… On 12 November the Taoiseach received a phonecall from the President of the European Commission expressing the concern of the G20 at the risk to international financial stability posed by the fragility of the Irish situation”.56

Brian Cowen advised:

“…On 12 November the ECB, the governing council, decided that it could not sustain its large exposure to Irish banks. On the same day, ECB-EU sources commenced off-the-record media briefings leading to reports that Ireland would need a bailout and the discussions were under way. On 13 November there were internal discussions with myself, Minister Lenihan and key officials. We were clear that if discussions were to take place it would be, if you like, talks about talks….”5758

Further testimony was given to the Joint Committee by Alan Ahearne in this regard:

“Reuters or one of the news agencies had a story that said Ireland applying for the ... is going to apply for a programme. So I called back and said “What’s this all about?” and I was told at that stage that a call had come in, I think, the night before, sorry, or at some stage around then, from Olli Rehn to Brian Lenihan and he had said - in the conversation as it was related to me - “Hi Brian. It’s midnight in Seoul. Things have changed.” And what he meant was... “Things have changed.”, is that on the Monday or Tuesday, there was this potential to explore a precautionary programme but by the time we got to later that week there was no time to do that.”59

The Irish authorities were not pleased that these discussions had been made public, albeit through anonymous briefings to the press. As Kevin Cardiff explained to the Joint Committee:

“It was, though, clearly inappropriate that at the outset, at the point when we were trying to make decisions, that back door briefings of the media should be used to undermine our position in the markets so as to add to our pressures. Democratic systems should not rely on undermining reputations and distributing misinformation via anonymous briefings.”60

It is unclear whether or not these discussions and anonymous briefings had a material effect on the need for official external assistance. However, it would appear that from this point onwards, Ireland was more likely to enter into a Troika Programme, pending negotiations and a decision by the Government.

In the midst of these considerations and discussions, public speculation on the part of the media as to Ireland’s possible entry into a bailout programme was growing. Public pronouncements on the part of two Cabinet Ministers on the weekend of 13-14 November 2010 to the effect that the Government was not about to seek financial aid from the Troika, was followed by an intervention from the Central Bank Governor Patrick Honohan on 18 November 2010.61 The Governor’s comments were at odds with the official line from Government at the time regarding the purpose of discussions.

Kevin Cardiff told the Joint Committee:

“While the discussions were due to get under way, there was some surprise news. Patrick Honohan, the Central Bank Governor, telephoned RTÉ from Frankfurt. He announced to the Irish public that he expected these discussions to lead to a very substantial EU/IMF bailout package, without notice to the Minister for Finance or the Government…”62

When the Joint Committee asked Patrick Honohan about this intervention, he said:

“…and I think if you look at the wording of the statement ... of the interview that I gave on “Morning Ireland” you’ll see I went very, very close to saying that the ECB would provide all the finances that would be necessary….”63

He continued:

“Now, was I trying to contradict the Taoiseach? Was I trying to contradict other Ministers who’d said that? No, I wasn’t trying to do that. Maybe I wasn’t sufficiently attuned to the political happenings that were going on in Dublin because I’d been in Brussels and Frankfurt and, you know, doing all these discussions. When the Taoiseach said ... of the time said, “We’re not in negotiations,” I took that to be the standard thing ... understood, by informed people, to say, “Oh you’re not in negotiations, you’re in pre-negotiations”.64

In his evidence to Joint Committee, Brian Cowen commented on Patrick Honohan’s interview in the following terms:

“… and I just want to emphasise this, he did make the point in the interview that this is a matter for the Government and he went on to give an opinion…”65

In her evidence, Cathy Herbert, Special Adviser to Minister Brian Lenihan said:

“…He was irritated by it. Brian Lenihan was only ever irritated briefly. I mean, not long afterwards he said to me, you know, “The Governor had his own pressures. He’s a member of the ECB. He’s independent in the exercise of his duty.” He [Brian Lenihan] had appointed him as Governor and he got over it….”66

The public was now alive to the likelihood that Ireland would need an external assistance programme of some form. The Joint Committee queried whether the Cabinet had been kept informed of the advanced stage of discussions and whether misinformation in the public domain caused confusion.

Brian Cowen told the Joint Committee:

“There were discussions going on, we had not agreed to go into a programme, we had not applied for a programme, but we were in discussions about the possibility. But until we knew where that was going we weren’t even acknowledging that, not because you’re trying to mislead anyone, but you don’t want the European people you’re talking to think that this is all ... that you can say what you like to us and we’re going to go in anyway.”67

Brian Cowen further elaborated that the failure of the Government to share a united message was due to a “miscommunication, there was a miscommunication that happened, and as head of the Government I should take responsibility for that.”68

On Saturday, 20 November 2010, the Minister for Finance received a letter from Jean-Claude Trichet dated 19 November 2010. The letter stated:

“…It is the position of the Governing Council that it is only if we receive in writing a commitment from the Irish Government vis-a-vis the Eurosystem on the four following points that we can authorise further provisions of ELA to Irish financial institutions:

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Patrick Honohan described this letter as “gratuitous” :

“Meanwhile ECB officials made public and private overtures to the Irish Authorities to encourage application for a programme. Given the views of Irish officials, already preparing the ground for a programme, these overtures were behind the curve and as such can be considered at best as having been largely gratuitous. This includes the letter of the ECB President to the Minister for Finance on November 19.”70

Jean-Claude Trichet’s letter caused the Irish Government position to crystallise. The situation was clear: if the terms of the letter were not adhered to, Irish Covered Institutions would not receive any further emergency liquidity assistance from the ECB.71

Kevin Cardiff explained the significance of this letter in his evidence:

“The ECB advice in regard to entry to the EU-IMF programme was specific, it was directly tied to conditions they had outlined in correspondence, and there were consequences for non-compliance. The ECB had its reasons and I don’t say that they were wrong from their perspective, certainly, but their view was clearly an important pressure point.”72

Jean-Claude Trichet was asked about this letter at an event organised by the Institute of International and European Affairs held on 30 April 2015 at Kilmainham Hospital, Dublin.73 It was put to Jean-Claude Trichet that it was a clear and unambiguous threat that, if Ireland did not apply for a bailout programme, the ECB would turn off the lifelines for the Irish Covered Institutions.74 His response was as follows:

“…And I have to say that the letters, the exchange of letters, made clear that as lender of last resort, looking at a situation which was deteriorating by the day, we could not continue to be the lender of last resort to institutions which were clearly considered insolvent by all their environment, their financial environment.”75

He further stated:

“The letter is there. It was returned in order to avoid any ambiguity. There is not any ambiguity thanks to the letter. You see exactly what the letter is saying but I didn’t ask anybody to speak publicly on such matters”.76

He added:

“the main argument[s] that explains the decision of the Government of Ireland at the time”77 and said that “combined with other factors, such as the ever-worsening fiscal situation, the Irish Government was confronted with no alternative but to ask for official support”.78

As the decision to formally apply for a Troika Programme came into view, Irish Government officials were concerned that Ireland’s corporation tax rate might become a feature in any negotiations. As Kevin Cardiff stated to the Joint Committee:

“There would be important obstacles to agreement. It seemed likely that demands to change our corporation tax rates would be made by some countries. Others might seek collateral for their loans, which could create enormous practical, political and legal obstacles.”79

It was made clear by the Government that no concession would be made on the corporation tax rate due to its importance to economic recovery. As Brian Cowen told the Joint Committee: “…Efforts had been made from time to time to put our corporation tax rate on the agenda, which we refused to countenance…”80

Asked by the Joint Committee whether or not it was put to the Irish authorities that Ireland should increase its corporation tax rate, Dermot McCarthy told us:

“No, Deputy, I don’t believe so but I think the concern, the anxiety was that part of … this process, of course, required the agreement of the member states and that it was in the engagement with member states that the risk of such a condition … was feared might arise. And that was based on, if you like, the broad environment rather than specific messaging.”81

It is not clear if Ireland’s corporation tax rate was ever formally tabled by any of the Troika partners during the negotiations but the perception of a threat was real and, in securing a programme of assistance, the protection of the corporation tax rate was considered a “considerable win” .82

This view was endorsed by Ajai Chopra of the IMF in his evidence to the Joint Committee:

“…The corporate tax was a central feature of Ireland’s business model at the time, to the extent that a country has a business model, and even though there may be a good case to address this over the medium term, we did not think that this needed to be a part of the programme at that time...”83

The Cabinet met on 21 November 2010 to formally consider (and subsequently agree to) entering negotiations on a programme of assistance with the Troika.84 After a Eurogroup meeting on 21 November 2010, the Irish Government officially requested financial support from the European Union, the IMF and the Euro Area member states.

Formal negotiations took place from 21 November 2010 to 26 November 2010.85

Work on a four-year recovery programme was close to finalisation prior to the commencement of negotiations. The programme, ‘National Recovery Plan, 2011 - 2014,’86 specifying the steps to reach a further €15 billion adjustment in the State finances, was reviewed and approved by the Government on 24 November 2010, while negotiations were ongoing.

As Brian Cowen said in his evidence:

“…When the Troika did get it [National Recovery Plan] after Cabinet approval, they agreed to adopt it as a central plank of the programme. It was, as we believed it to be, rigorous and realistic and designed to meet the economic challenges we faced. The EU-IMF programme was finalised and adopted by Government on 27 November 2010 and one additional year was allowed to reach the general 3% deficit threshold if required…”87

The view of the Troika on the National Recovery Plan is also worth stating:

In his evidence, Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs with the European Commission said: “...I think we supported very strongly the national recovery plan that the Irish Government had put in place and were elaborating at the time....”88

Ajai Chopra stressed the importance of Ireland having taken ownership of economy recovery by formulating its own plan: “…the important thing is much of the programme was designed by the Irish authorities...”89

Kevin Cardiff summed up the content of the Troika negotiations to the Joint Committee:

“On other areas of the negotiation with the external partners, we strove hard to get the best deal possible for Ireland and, indeed, we achieved some considerable wins. First, no threat to our corporation tax system, on which many jobs depended and depend; no collateral requirement for the loans; adoption, wholesale, of the Irish four-year plan – national recovery plan; agreement to Irish figures for fiscal adjustment, so no addition front-loading of the fiscal adjustment beyond the numbers that had already been announced by the Irish Government. At some point, we got an extra year to make the overall fiscal adjustments required. We got a tacit – unfortunately not explicit, but a tacit – ECB commitment to continued banking system support and we got a “no fire sales” approach to bank deleveraging, which probably saved us some billions later.”90

Ultimately, the Cabinet met on 27 November 2010 and agreed to enter an ‘EU-IMF financial assistance programme’91

The Troika Programme comprises two distinct parts:

The Troika Programme endorsed the Government’s budgetary adjustment plan of €15 billion over the subsequent four years (2011-2014) and the commitment for a €6 billion front-loading of fiscal adjustments and other measures in 2011.93 The details of the Troika Programme closely reflected the key objectives set out in the National Recovery Plan.

| Use of funds | Eur bln | % | ||

| Banking system | 10 | 12% | Immediate recapitalisation | |

| Financing of State | 50 | 59% | ||

| Contingency | 25 | 29% | Banking system supports | |

| Total | 85 | 100% | ||

The following provides a summary of the National Recovery Plan as prepared by the Government in 2010:95

According to Brian Cowen:

“These spending cuts and tax increases involved a total adjustment of over €15bn in the four budgets we introduced, including the 2011 budget. It represented two thirds of the total required adjustment to bring the budget deficit below 3% as required by EU Stability and Growth Pact rules…”

He added that:

“…the EU-IMF programme … provided the means and the Credit Institutions Act 2010 provided the legislative basis to implement the necessary restructuring and downsizing of a domestic banking system to a more sustainable model for the future…”96

| Lenders | Eur bln | % | Interest rate p.a. | |

| EU & Bilateral lenders | 22.5 | 26% | 6.05% | EFSF (European Financial Stability Fund) |

| EU & Bilateral lenders | 22.5 | 26% | 5.70% | ESFM (European Financial Stability Mechanism) |

| NPRF | 17.5 | 21% | National Pensions Reserve Fund | |

| IMF | 22.5 | 26% | 5.70% | EFF (Extended Fund Facility) |

| Total | 85 | 100% | ||

| Source: Irish Gov press release Nov 28, 2010 Source: Interest rates NTMA note Dec 1, 2010 |

||||

Source: Government Statement Announcement of joint EU - IMF Programme for Ireland97

The “Bilateral lenders” (namely the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark) each contributed separately to the Troika Programme as they are not part of the Eurozone.98

Ireland contributed €17.5 billion from the National Pensions Reserve Fund as part of the Troika Programme. Such a measure was alluded to in the correspondence from the ECB of 19 November 2010:

“The plan for the restructuring of the Irish financial sector shall include the provision of the necessary capital to those Irish banks needing it and will be funded by the financial resources provided at the European and international level to the Irish Government as well as by financial means currently available to the Irish Government, including existing cash reserves of the Irish Government.”99

Brian Lenihan stated in the Dáil on 1 December 2010:

“Furthermore, the State is in the happy position of being able to contribute €17.5bn towards the €85bn from its own resources, including the National Pension Reserve Fund. Why would we borrow expensively to invest in our banks when we have money in a cash deposit earning a low rate of interest.”100

In evidence, Marco Buti stated that he regarded the contribution as an appropriate and prudent move from the perspective of the financial markets. He said it was not a precondition but that it impressed the markets and also saved the country money.

Ireland was in a precarious fiscal state on joining the Troika Programme. The Current Budget balance in 2010 was significantly negative and the outlook for 2011 was scarcely better, as shown in the table below.101

| Budgetary Data | |||||

| Table A.4.1 Budgetary Projections 2010-2014 | |||||

| CURRENT BUDGET | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

| Expenditure | € bn |

€ bn | € bn | € bn | € bn |

| Gross Voted Current Expenditure | 54.8 | 52.8 | 50.9 | 49.4 | 48.0 |

| Non-Voted {Central Fund) Expenditure | 6.4 | 6.8 | 8.8 | 10.0 | 11.0 |

| Gross Current Expenditure | 61.2 | 59.7 | 59.7 | 59.4 | 59.1 |

| less Expenditure Receipts and Balances | 13.8 | 12.7 | 13.0 | 13.4 | 13.9 |

| Net Current Expenditure | 47.4 | 47.0 | 46.7 | 46.0 | 45.2 |

| Receipts | |||||

| Tax Revenue | 31.5 | 33.4 | 36.3 | 39.2 | 42.2 |

| Non-Tax Revenue | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Net Current Revenue |

34.2 | 35.4 | 37.5 | 40.1 | 43.1 |

| CURRENT BUDGET BALANCE |

-13.2 | -11.6 | -9.2 | -5.9 | -2.1 |

Source: Budget 2011 Table A.4.1

The overall underlying General Government Balance was estimated at the time to be 11.7% of GDP.

Against the backdrop of a bad fiscal situation and serious liquidity problems in the banks, the first Budget under the National Recovery Plan provided for adjustments of €6 billion, mainly in the form of higher taxation and restrictions on current and capital expenses. The introduction of the Universal Social Charge (USC) and the reduction of tax bands were some of the tax revenue increase measures taken.

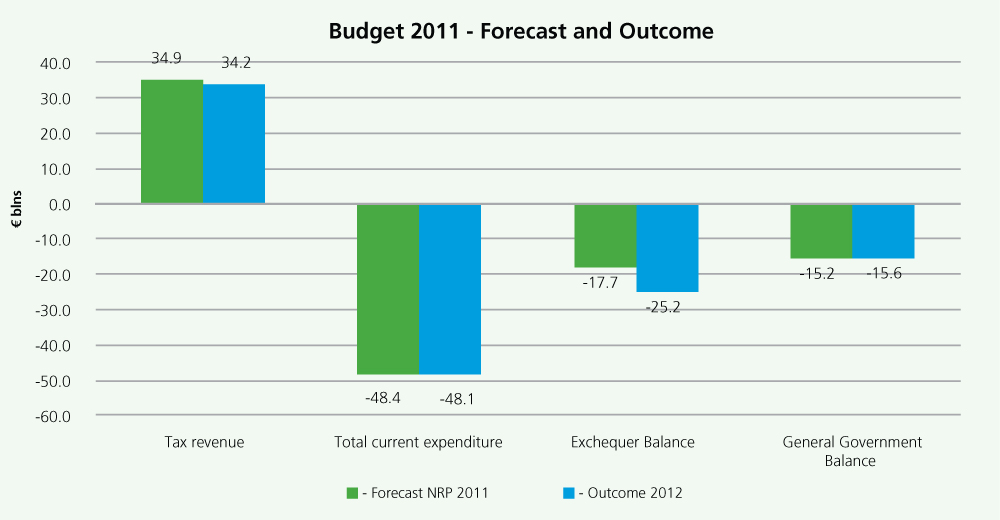

Estimates given in late 2010 turned out to be very close to the actual outcome in 2011.

Graph prepared on behalf of the Joint Committee using information sourced from www.budget.gov.ie/budgets103

The substantially larger than anticipated Exchequer Deficit resulted from an amount of over €7.5 billion for bank recapitalisations (See Chapter 8 Post Guarantee developments). Tax revenue rose by more than €2.6 billion, but remained slightly behind the forecast. This was mainly due to the lack of growth: GDP sank by 1.3%, as against a forecast of +1.3%, and the unemployment rate rose to 14.3% versus an estimate of 13.2%. Income tax, corporation tax and VAT stayed slightly behind predictions.

Government debt rose to €169 billion or 109% of GDP at year end-2011 but at least a further widening of the underlying fiscal structural deficit was halted.

The new Government, elected in March 2011, sought to amend certain terms of the Troika Programme by agreement with the Troika Partners. This amendment led to reduced interest rates and the extension of loan maturity terms by an additional 7 years,104 reducing the cost of servicing the debt over a longer period.

In September 2011, the Government negotiated several changes to the Troika Programme of assistance as follows:105

Ajai Chopra gave evidence to the Joint Committee regarding these changes:

“I wouldn’t say there were fundamental changes. There were a number of small changes, and actually not a very large number. There was the issue of the minimum wage, which was taken ... which the new Government did not continue with, with the proposed policy of the previous Government. There was a little bit more ... there was more emphasis ... there was some switch in some fiscal measures geared a little bit more towards job creation. So I wouldn’t say there were any fundamental changes”.107

Upon these changes being agreed, the new Government also made changes to the National Recovery Plan. Ajai Chopra gave the following view:

“The national recovery plan was put forward by the previous Government, and you know, as we have said, the subsequent Government modified a few elements of it but the fundamental structure remained.”108

On the issue of the interest rates applied by each of the Troika partners to the Troika Programme loans, the following document from the Department of Finance explains the initial agreement:

“The average interest rate on the €67.5 billion available to be drawn from these three external sources under the EU-IMF programme is 5.82 per cent on the basis of market rates at the time of the agreement. The actual cost will depend on the prevailing market rates at the time of each drawdown. The average life of the borrowings, which will involve a combination of longer and shorter dated maturities, under each of these sources is 7.5 years and the interest rates applying to borrowings from each are set out below based on market rates at the time of the agreement.”109

From the beginning of the Troika Programme, there was concern as to the higher rate being applied on the EFSF and EFSM facilities vis-à-vis the terms of the other facilities. John Corrigan, in providing evidence to the Joint Committee, said:

“the EFSF and the EFSM […] were pricing those [their loans] off the facilities that they had given to Greece. Initially the discussions were they were looking at giving us very short-term facilities when we engaged with them in November, and we persuaded them in those discussions that if we were to go for a programme, that they ... for any programme to be meaningful, they would have to look at maturities of the order of seven years or beyond. They did, they did go for the extended maturity but the initial interest rates were well over 5% and they were ... they were reduced, I think, during the course of ... in mid-July 2011.”110

When asked about the terms of the Troika Programme, Patrick Honohan, said that:

“there were subsequent, considerable improvements in the terms of financing, not least through the reduction of EU interest rates from the initial level of about 5.7%, 5.8% per annum and the lengthening of the loan maturities and subsequently through the carefully designed financial arrangements around the liquidation of IBRC, especially the so-called promissory note exchange.”111

He further elaborated: “these improvements, combined of course with close adherence to the budgetary targets in the following three years, allowed the Government to take the decision to exit the programme on schedule at the end of 2013.”112

One explanation for the interest rate negotiation and reduction was provided by Kevin Cardiff:

“It wasn’t much negotiable at that point. The Minister had done some talking to other Ministers in the Eurogroup and so forth, so far as I know. It was fairly clear there was not much shift on that. So the focus was on other things. But even in the memo for Government saying “Let’s join this programme” , there was a line saying “and by the way, the interest rate could be lower and we are going to continue working on that”. And there was, you know, people were making approaches as early as February, I think February, certainly March ... of the ... of the following month. We almost succeeded and it would have been a pity because, in fact, we got an even bigger reduction than we had been looking for or than we had been hoping for, let’s say, in July. So in a sense, the little bit of delay helped. We also had in mind, I mean, we talk about other people being cynical, we were a bit cynical ourselves. We also had in mind that if things got worse in other parts of Europe, the case for an interest rate reduction for those other parts of Europe would be much stronger than for Ireland even and that we would be able to piggy-back on that, which is more or less what happened.”113

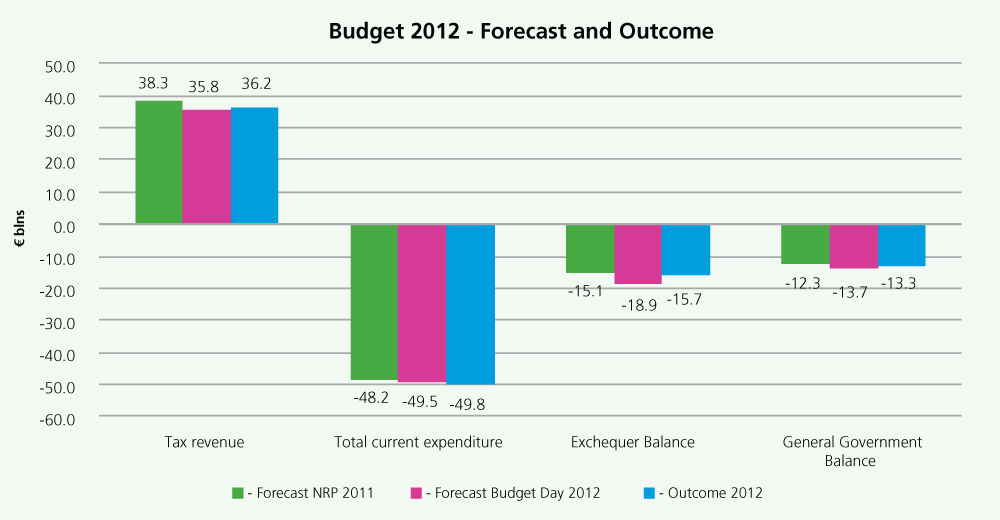

Budget 2012 marked the second year under the National Recovery Plan. It was also the first Budget announced by Michael Noonan as the new Minister for Finance.

The 2012 Budget was prepared within the parameters of the National Recovery Plan and adherence was closely observed by the Troika partners under the EU-IMF Financial Assistance Programme. Although there was limited room for manoeuvre, some flexibility was given, as an additional year had been granted in November/December 2010 to return to within the target deficit of 3% of GDP under the Stability and Growth Pact.

€3.8 billion of additional fiscal adjustments was announced in Budget 2012. €750 million capital expenditure savings and €1.45 billion current expenditure consolidation were implemented. Additional new tax measures accounted for €1.6 billion approximately.

Of note were the introduction of the Household Charge, which led to the planned introduction of the Property Tax in 2014, an increase in the CGT rate from 25% to 30%, the increase of the VAT rate from 21% to 23%, changes to Pay-Related Social Insurance (PRSI) employer contribution and increases of carbon and motor tax.

Graph prepared on behalf of the Joint Committee using information sourced from www.budget.gov.ie/budgets115

The chart above shows original and adjusted estimates. Tax revenues remained behind the original estimates when the National Recovery Plan was announced but rose by more than €2 billion, compared to 2011 and slightly exceeded the Budget Day projections. After the fall in the previous year, GDP had started to recover and grew by 5.5%. This recovery had not fed through to the unemployment rate, which rose higher than expected, to 14.7% in 2012. Rates of 14.1% and 12% had been forecasted one and two years earlier.

Despite all the adjustments, it had still been expected that the Exchequer Balance would remain substantially negative and that is what transpired. Overall, Government debt rose to €192 billion or 117% of GDP at year end-2012.116

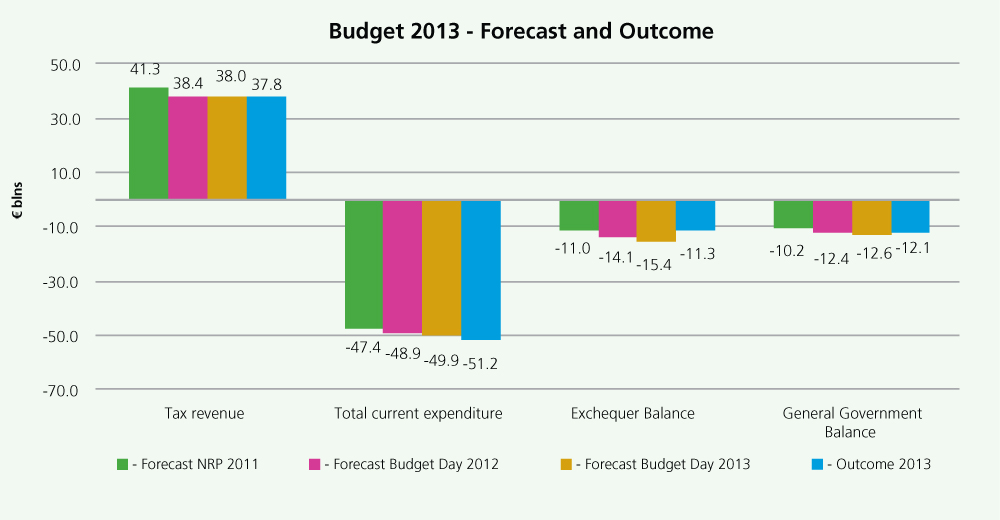

The third Budget under the National Recovery Plan included further fiscal adjustments amounting to €3.5 billion, as required under the EU-IMF Financial Assistance Programme. Adjustments of a further €3.1 billion and €2.0 billion were expected for the following two years in order to bring the Government Balance into line with the target set in the Stability and Growth Pact.118

The Local Property Tax was introduced in the 2013 Budget as one of the main taxation measures. Substantial increases in excise duties and motor tax were also announced. PRSI and Pension Fund changes were also contributing significantly to revenues.

Graph prepared on behalf of the Joint Committee using information sourced from www.budget.gov.ie/budgets119

The chart above shows original and adjusted estimates. Tax revenues increased by a further €1.6 billion to €37.8 billion but again remained behind the original forecasts. Expenditure grew considerably stronger than expected for the first time since the Budgets of 2009.

Despite the widening gap between revenues and expenses, the Exchequer Deficit was reduced to some €11 billion. This was mainly due to lower debt servicing costs after the restructuring in February 2013 of the Promissory Note Debt and following additional capital receipts of €2.3 billion from the sale of Irish Life plc and Contingent Capital Notes in Bank of Ireland.120

The Irish economy had built upon the signs of recovery seen in 2012. GDP growth reached 6.7% and the unemployment rate fell from 14.7% to 13.5%. House prices in Dublin City rose strongly in the second half of the year and started recovering in the rest of the country.

Despite the major fiscal adjustments and signs of economic recovery, the Exchequer Balance remained substantially negative. Government debt rose to €215.6 billion or 123% of GDP at year end 2013. Further adjustments were still needed.

It was agreed in a ‘Memorandum of Understanding between the European Commission and Ireland’ , signed by the Minister for Finance, the Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland and the European Commission,121 that implementation of the measures under the Troika Programme would be monitored using continuous performance criteria, indicative targets and structural benchmarks and by means of quarterly programme reviews in compliance with requirements under the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP).

Following each quarterly review, funds were released as per the Programme, subject to the agreement of all parties. The IMF produced and published a quarterly report after each review, 12 reviews in total. The final report was dated December 2013.122

Marco Buti, European Commission stated in evidence that, when implementing the Troika Programme, the Commission had “many contacts with the social partners” .123 Ajai Chopra, IMF, also stated that the Troika had met with “a wide range of social partners.”124

Both witnesses testified that shielding the most vulnerable from the cutbacks was a central objective. Ajai Chopra said:

“…Protecting the socially vulnerable at a time of difficult economic adjustment was a central policy goal. Even before the program started, deep fiscal consolidation had been implemented in 2008, 2009 and 2010 with comparatively modest social distress.”125

Marco Buti said:

“…If one looks at the ... at indicators of, let’s say, inequality of distribution of income, of material deprivation, etc., you can see that the operation of the tax and benefits systems helped substantially to lessen the impact. This does ... I am not minimising at all the fact that it was harsh for everybody, but in terms of overall, let’s say, fairness considerations, I think the programme was implemented adequately…”126

Conditions improved slowly as the Programme continued. In July 2012, Ireland re-entered the International Bond Markets and Moody’s raised the Sovereign rating back to investment grade, to Baa3, in January 2014.127 As John Corrigan said in his evidence:

“...The investor relations programme yielded relatively early results when, in 2012, we raised €5.2bn on the market in long-term debt, regained regular access to the short-term markets and succeeded in reducing the outstandings on the January 2014 bond to €7.6bn...”128

Following a successful 12th quarterly review at the end of 2013, Ireland exited the Troika Programme.129 The Government agreed to exit the Programme on 14 November 2013 without the need for a pre- arranged precautionary facility or backstop.130

The IMF, in a press release dated 19 December 2013, commented that Ireland had “pulled back from an exceptionally deep banking crisis, significantly improved its fiscal position, and regained its access to the international financial markets…”131

As mentioned previously in this Chapter, the ECB did not cooperate with the Banking Inquiry, undermining the Joint Committee’s ability to investigate matters fully (noting that the Joint Committee did put questions to Jean-Claude Trichet at the Institute of International and European Affairs event held on 30 April 2015 at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham Hospital). The Joint Committee believes that there is a serious democratic deficit when it comes to the ECB’s accountability to the Inquiry in terms of significant decisions taken by the Irish Government that it was directly involved in over the period under investigation.

Chapter 10 Footnotes

1. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-004.

2. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-029.

3. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-004.

4. Michael Somers, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00093-042.

5. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-015.

6. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-017.

7. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-017.

8. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-035.

9. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-011.

10. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-016.

11. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-083.

12. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-043/044.

13. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-007.

14. The Irish Banking Crisis regulatory and Financial Stability Policy, 2003-2008, PUB00075-131.

15. Department of Finance submission to the Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015, DOF07852-005.

16. Ex post Evaluation of the Economic Adjustment Programme: Ireland, 2010 – 2013, Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, July 2015, PUB00356-025.

17. Extract from OECD journal financial market trends volume 2010, PUB00390-001.

18. Simon Carswell, Author & Journalist, transcript, PUB00179-033.

19. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-059.

20. Extract from OECD journal financial market trends volume 2010, PUB00390-002.

21. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-015.

22. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-015.

23. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-037/059

24. Dermot McCarthy, former Secretary General, Department of the Taoiseach and Secretary General to the Government, transcript, INQ00108-026.

25. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-018.

26. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-029.

27. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, transcript, PUB00349-006.

28. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-065.

29. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-005.

30. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-005.

31. This was referred to in a tweet by David McWilliams, as reported in Kevin Cardiff statement, KCA00002-134.

32. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-133.

33. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-134.

34. Simon Carswell, Author & Journalist, transcript, PUB00179-033.

35. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-004.

36. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-066.

37. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement KCA00002-127.

38. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-130.

39. Marco Buti, Director General for economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-021.

40. Letter from Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, to Brian Lenihan, former Minister for Finance, dated 15 October 2010, DOF03413.

41. Letter from Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, to Brian Lenihan, former Minister for Finance, dated 15 October 2010, DOF03413.

42. National Recovery Plan 2011-2014, DOF07578.

43. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript PUB00351-044.

44. National Recovery Plan 2011-2014, DOF07578.

45. National Recovery Plan 2011-2014, DOF07578.

46. Department of Finance-Banking Inquiry Team – Information Memorandum DOF07852-004.

47. National Recovery Plan 2011-2014, DOF07578.

48. Alan Ahearne, former Special advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-018.

49. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-005.

50. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-011.

51. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-136

52. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-138.

53. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-138.

54. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-139.

55. See Glossary of Terms.

56. Dermot McCarthy, former Secretary General, Department of the Taoiseach and Secretary General to the Government, statement, DMC00001-004.

57. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-012.

58. Marco Buti gave evidence that he was not aware of the briefings described by Brian Cowen. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-022.

59. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-019.

60. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-007.

61. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-165.

62. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-172.

63. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-065.

64. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-065.

65. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-093.

66. Cathy Herbert, former Special Advisor to former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00091-008.

67. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-087.

68. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-088.

69. Letter from Jean-Claude Trichet, former President of the ECB, to Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, dated 19 November 2010, DOT00376.

70. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, statement, PHO00009-005.

71. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-172.

72. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-006.

73. The circumstances in which he answered questions are set out in Appendix 1 of this report.

74. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, transcript, INQ00140-033.

75. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, transcript, INQ00140-038.

76. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, transcript, INQ00140-040.

77. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, transcript, INQ00140-007.

78. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President, ECB, transcript, INQ00140-026.

79. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-160.

80. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-012.

81. Dermot McCarthy, former Secretary General, Department of the Taoiseach and Secretary General to the Government, transcript, INQ00108-037.

82. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-007.

83. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-026.

84. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-012.

85. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-089.

86. National Recovery Plan 2011-2014, DOF07578.

87. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-013.

88. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-021.

89. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript INQ00101-030.

90. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-007/008.

91. Letter from Minister for Finance to Olli Rehn, former Comissioner on Economic and Monetary Affairs, European Comission; Dominique Strauss-Khan, former Managing Director, IMF and Jean-Claude Trichet, former President of the ECB, DOF03431.

92. The timeframe was extended by one year to 2015- Government statement, 28 November 2010, DOF03444-002.

93. Government Statement Announcement of joint EU - IMF Programme for Ireland, DOF03444.

94. In accordance with the Government announcement of Troika Programme for Ireland, 28 November 2010, DOF03449-004

95. National Recovery Plan 2011-2014, DOF07578-005.

96. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-013/014.

97. Government Statement Announcement of joint EU - IMF Programme for Ireland, DOF03444.

98. Government Statement Announcement of joint EU - IMF Programme for Ireland, DOF03444-003.

99. Letter from Jean-Claude Trichet, former President of the ECB, to Brian Cowen 19 November 2010, DOT00376-003.

100. Statement by Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan T.D. on the EU/IMF Programme for Ireland and the National Recovery Plan 2011 to 2014, DOF03449-004.

101. National Recovery plan 2011-2014, DOF07578-110.

102. Source for Budget 2011 from http://www.budget.gov.ie/budgets/2011/2011.aspx

103. This graph was prepared solely to assist the reader. It does not constitute evidence and was not presented as evidence to any witness providing testimony to the Inquiry.

104. From 12.5 to 19.5 years for EFSM loans and from 15 to 22 years for EFSF loans. This extension should also increase the period under which Ireland will be under Post-Programme Surveillance (PPS). This should normally run until 75% of the assistance has been paid back. Source: EC Ex post Evaluation of the Economic Adjustment Programme Ireland, 2010-2013, PUB00356-042

105. Government’s Negotiation of Programme of Assistance and Interest Rate Savings, DOF03494, DOF03493-001.

106. These figures were only valid when all of the €45billion had been drawn down and for as long as the amounts remained outstanding.

107. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF transcript, INQ00101-013.

108. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-030.

109. EFSM Interest rates, DOF03793-001.

110. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-022.

111. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-004.

112. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-005.

113. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-044.

114. Source for Budget 2012 from http://www.budget.gov.ie/budgets.2012/2012.aspx

115. This graph was prepared solely to assist the reader. It does not constitute evidence and was not presented as evidence to any witness providing testimony to the Inquiry.

116. New Government Finance Statistics issued by CSO, www.cso.ie.

117. Source for Budget 2013 from http://www.budget.gov.ie/budgets/2013/2013.aspx.

118. General Government Balance and Fiscal Consolidation Forecasts 2013 – 2015, Medium-Term Fiscal Statement November 2012 Pg5, http://www.budget.gov.ie/budgets/2013/2013.aspx.

119. This graph was prepared solely to assist the reader. It does not constitute evidence and was not presented as evidence to any witness providing testimony to the Inquiry.

120. http://oldwww.finance.gov.ie/viewdoc.asp?DocID=7505, Bank of Ireland - Disposal of Contingent Capital Notes by the Minister for Finance.

121. Memorandum of Understanding between European Commission and Ireland, DOF03460-011.

122. Twelfth review under the extended arrangement and proposal for post-program monitoring dated December 2013, DOF00740. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2013/cr13366.pdf

123. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-029.

124. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-025.

125. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, statement, ACH00001-012.

126. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-030.

127. The Irish financial assistance programme – Department of Finance, DOF07710-022.

128. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-006/7.

129. The terms and conditions of the programme loan agreements and financial frameworks are still applicable in 2015 and continue to be monitored on an ongoing basis. Both the IMF and the EU conduct post-programme monitoring following completion of a programme. This provides for regular missions and reports on a bi-annual basis which will continue until 75% of the financial assistance has been paid back. Refer to Memorandum for Government 12th Review mission of the EU-IMF programme of financial support for Ireland, DOF00459-003.

130. Memorandum for Government 12 Review mission of the EU-IMF programme of financial support for Ireland, DOF00459-003.

131. IMF Survey December 19, 2013, DOF00739-001.