Back to Chapter 7: The Guarantee

Following the issuance of the Guarantee, the Financial Regulator issued a letter to all Covered Institutions, advising them that the existence of the Guarantee should not be used as a marketing or advertisement tool to attract funding which could potentially create liquidity distortions in the banking markets.1

In the short-term, the Guarantee had stabilised and improved the liquidity position of the Covered Institutions.2 However, by January 2009 the Guarantee was “just about” working with regard to providing non-ECB liquidity to the banks.3

In testimony to the Inquiry, former Group Chief Executive of Ulster Bank, Cormac McCarthy, in response to questioning on the impact of the Guarantee on Ulster Bank, said that it was:

“Very significant. Within a period of weeks there were billions of wholesale customer deposits and a degree of retail deposits flowed out of the institution.”4

This was reiterated in the RBS Group Annual Report and Accounts 2008, which stated:

“The governments of some of the countries in which the Group operates have taken steps to guarantee the liabilities of the banks and branches operating in their respective jurisdiction. Whilst in some instances the operations of the Group are covered by government guarantees alongside other local banks, in other countries this may not necessarily always be the case. This may place subsidiaries operating in those countries, such as Ulster Bank Ireland Ltd, which did not participate in such government guarantee schemes, at a competitive disadvantage to the other local banks and therefore may require the Group to provide additional funding and liquidity support to these operations.”5

In October 2008, the British Government announced that they would recapitalise Ulster Bank’s parent company, RBS.6 By December of that year Great Britain owned 58% of the shares.7 Therefore, according to Richie Boucher, Group Chief Executive in BOI, Ulster Bank “…had been, effectively, nationalised by the British Government, so the depositors had an implicit guarantee.”8

The Joint Committee considered whether or not the Guarantee could have been rolled back in part or rescinded for one or more of the Covered Institutions as the scale of the potential liabilities in the Covered Institutions were discovered during Project Atlas.9 This is also discussed in Chapter 7.

Notwithstanding the moral obligation, there was an opportunity between the announcement of the Guarantee and the formal designation by the Minister for Finance of the Covered Institutions under the Credit Institutions (Financial Support) Scheme 2008 (CIFS)10 on 24 October 2008, to change the terms and scope of the Guarantee. For example, one of the banks could have potentially been excluded. When questioned about this option, Kevin Cardiff said:

“…remember, a lot of new money came in on foot of the guarantee but it didn’t come in four weeks later. It started coming in immediately. So, that you would pull out of the guarantee with hundreds of millions, billions and millions of deposits, based explicitly on it, would’ve created a ... would’ve created ... I don’t know. It would’ve been extraordinarily risky. But, no, … I don’t recall a discussion about pulling out at that stage. I think we’d gone beyond that point. In practical terms, we were beyond the no return point.”11

On the question of what might have had happened had a bank such as Anglo been kept outside of the Guarantee in the first instance, Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, said:

“…you could have let Anglo go on its own, you didn’t have to do anything, but the judgment was made that leaving a bank that, I think Governor Honohan in his report says was ‘of systemic importance‘, systemic not that we needed this bank but systemic importance in terms of the consequences. And one of the things that was apparent from the information given to the Government by the other banks was the other banks were distinguishing between Anglo and INBS and themselves and understandably so. But the report that they gave us of the reactions from the money markets was Ireland was untouchable. And if you have one bank go, given what was known as the overexposure to property, the ready consequence I assume … was they’d say, ‘These other banks have huge exposure to property. There may be distinctions but we’re not convinced and the whole lot goes.‘ … and that was the calculation made with regard to Lehman Brothers and it went so badly wrong and I think there was a huge fear that if that gamble is taken, that things would just be out of control. And those are the judgments that have to be made and were made.”12

There was a power in the CIFS to revoke the Guarantee under certain conditions. Section 8 of the CIFS provided:

“The Minister may review and vary the terms and conditions of this Scheme from time to time, at no later than six-month intervals, to ensure that it is achieving the purposes of the Act of 2008. At such a review, the Minister shall consider, inter alia, the continued requirement for the provision of financial support under this Scheme with regard to the objectives of this Scheme and section 2(1) of the Act of 2008. The results of any such review shall be provided to the European Commission.”13

When questioned about this, Paul Gallagher said:

“There’s a power to revoke it in the guarantee scheme if, for example, the conditions of the guarantee weren’t being complied with, otherwise it was intended to last for two years, subject to a review. And it was conditional on the basis which … or, sorry, it was conditional on the circumstances which required the giving of the guarantee continued, and if they didn’t continue, then the Minister was entitled to bring it to an end and would be required to do so by the EU.”14

However, rather than being shortened, the Guarantee was actually extended beyond the original end-date of 2010 through the Eligible Liquidity Guarantee Scheme.15

Separate, but related to the need to recapitalise and restructure the Covered Institutions, was the question of whether or not the Guarantee delayed vital bank restructuring. Governor of the Central Bank, Patrick Honohan stated the following in oral testimony:

“We were in suspended animation for two years. One of the things the guarantee did, and we were talking about the subordinated debt, but guaranteeing the senior debt had a double effect. It is not just a question of not paying those guys, but any restructuring of the banking system, like liquidating or closing, would have triggered immediate payment under the guarantee from the Government. That meant that doing something with Anglo Irish Bank or with INBS, all these things, could be considered at leisure, because there was nothing one could viably do until the end of September 2010 and by that stage the damage was done.”16

This was supported by Marco Buti, Director General for Economic & Financial Affairs, European Commission, in his evidence to the Joint Committee, where he said: “…the banks had to be restructured and, from that viewpoint, the blanket guarantee clearly did not help.”17

Michael Noonan, the Minister for Finance, said that the Guarantee should have been “…accompanied by a restructuring and a recapitalisation of the banks…” thereby possibly guarding against Ireland’s need to enter into a Bailout Programme two years later.18

In October 2008, Patrick Neary, former Chief Executive, IFSRA, appeared on RTE’s ‘Prime Time’ Programme. He said that Irish financial institutions were well capitalised in comparison to European banks. He was confident they would be able to deal with loan losses incurred during the ordinary course of business into the foreseeable future.19

That assessment had been supported only a few days previously by Merrill Lynch. In their advice to the Minister for Finance, relating to the liquidity and strategic options available to the Government on 28 September 2008 Merrill Lynch stated: “It is important to stress that at present, liquidity concerns aside; all of the Irish banks are profitable and well capitalised…”20

The then Taoiseach, Brian Cowen had also advised the Dáil on 30 September 2008 that: “while Ireland along with all developed economies has experienced a sharp decline in its property market, there is very significant capacity within the institutions to absorb any losses…”21

The then Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, met with the Governor of the Central Bank and the Financial Regulator to discuss the PwC reports generated for Project Atlas, which confirmed that the capital position of each of the institutions reviewed was in excess of regulatory requirements as at 30 September 2008.22

However, notwithstanding these positive assertions, over time, the Project Atlas reviews started to uncover evidence of a markedly different and less positive situation. In addition, the Minister for Finance was aware that international capital market expectations relating to capital levels in the banking sector had altered and that an injection of capital, by the State, would be required.23

Having completed their Project Atlas 1 review in September 2008, PwC24 were engaged once again on 9 October 2008 to review the financial and capital positions of the six25 financial institutions covered by the Guarantee (the Covered Institutions). This examination was known as ‘Project Atlas 2’ .26 PwC concentrated on reviewing a sample of loan books and losses, focusing initially on the top 20 borrowers in each Covered Institution, but this was subsequently extended to the top 50 borrowers, when evidence was found that a large number of borrowers had loans with two or more lenders.27

Part of the Project Atlas 2 review consisted of examining scenarios showing the impacts which various asset write-downs would have on Tier 1 Capital.28 However, these scenarios were based on unrealistically low impairment levels with the fall in asset values accelerating.29

The scope of Project Atlas 2 was further broadened in November 2008 to include a review, known as Project Atlas 3, of land and development loans and related loan security. On this occasion, PwC were tasked with assessing the top 75 land and development loans within the Covered Institutions as at 30 September 2008. As part of the process, Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL) were engaged to carry out a review of valuations on the underlying assets supporting the top 20 land and development exposures in each Covered Institution.30

The results of Project Atlas 3 showed significant differences on land and development loans between the Covered Institutions’ own valuations of €27.405 billion and the JLL valuations of €19.568 billion – a difference of €7.837 billion across the five of the Covered Institutions reviewed.31

| € in millions | OirL | OirL | OL | OL | OL |

|

JLL Valuations |

|||||

|

Land and Development |

6,129.1 |

1,710.6 |

2,826.8 |

5,178.1 |

125.4 |

|

Investment |

773.1 |

663.8 |

1,662.2 |

516.7 |

- |

|

Total |

6,902.2 |

2,374.4 |

4,489.0 |

5,694.8 |

125.4 |

|

Bank Valuations |

|||||

|

Land and Development |

7,929.7 |

2,853.5 |

3,861.2 |

7,967.0 |

218.1 |

|

Investment |

928.0 |

963.6 |

2,059.8 |

624.4 |

- |

|

Total |

8,857.7 |

3,817.1 |

5,921.0 |

8,591.4 |

218.1 |

Source: Project Atlas, Draft Property Values Review32

The material differences between JLL’s and the five Covered Institutions’ valuations in respect of their land and property loan portfolios highlighted falling asset values and served as a forecast of impending material losses on the Covered Institutions’ property-related loans. In this regard, John Corrigan, former CEO of the NTMA said:

“…clearly the property values continued to fall and the whole funding regime continued to come under more strain, so while they [i.e. the six Covered Institutions – the five in the above table plus IL&P] probably were solvent at that point in time [i.e. when Project Atlas was undertaken], clearly the situation deteriorated rapidly.”33

As set out in the table below, overall, PwC reviewed loans totalling €253 billion, of which €159.2 billion related to property backed lending. €62.6 billion of that latter amount related to land and development loans, with €30.3 billion connected to land-bank developments. This represented almost one fifth of total property-backed lending of €159.2 billion, over half of which were either unzoned or, if zoned, had no planning permission.

|

Oir L |

Oir L |

Oir L |

Oir L |

Oir L |

Oir L |

Combined Sep-08 €bn |

|

|

Land & Development |

23.7 |

13.1 |

19.7 |

5.6 |

|

0.5 |

62.6 |

|

Property Investment |

26.7 |

24.9 |

40.9 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

0.8 |

96.6 |

|

Property backed lending |

50.4 |

38 |

60.6 |

7.4 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

159.2 |

|

Other loans (non-personal) |

45.6 |

33.4 |

8.9 |

2.2 |

3.2 |

0.5 |

93.8 |

|

Total Loans (ex. Personal) |

96 |

71.4 |

69.5 |

9.6 |

4.7 |

1.8 |

253.0 |

Source: Merrill Lynch and PwC summary34

Michael Somers, former Chief Executive, NTMA, said the following in his evidence:

“When the Pricewaterhouse report came in, I must say I was flabbergasted when I saw the size of the loans … which were advanced by the Irish banking system to individuals. I mean, they ran to billions. And I think I wrote to the Minister for Finance, he’d asked me to write a letter to him about what I thought of the overall economic and financial scene, and I wrote to him and one of the things I mentioned was that some individual had loans from the banking system equivalent to 3% of our GNP, which I thought was absolutely staggering.”35

It also transpired that large sums had been lent to a small number of developers, many with exposures to numerous banks. In this regard, Denis O’Connor, Partner with PwC said:

“…top ten borrowers had loans of €17.7bn with the six guaranteed banks and that was before any additional borrowings they had in Ulster Bank or Bank of Scotland Ireland.”36

John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, suggested in his evidence that this was “…information the regulator didn’t seem to have up until that.”37

David Doyle, former Secretary General in Department of Finance, noted that PwC “…in the course … of a couple of days were able to feed us [Department of Finance] information about the liquidity exposures, information that we [Department of Finance] didn’t have otherwise.”38

However, in his evidence, Patrick Neary, former Chief Executive, IFSRA, said that PwC were engaged because they had the resources to promptly carry out the work required and that PwC’s findings simply confirmed information the Financial Regulator already had.39

Asked to respond to the figures obtained from the Project Atlas reviews, representatives of the banks gave varying testimony. Brian Goggin, former Group Chief Executive of BOI stated:

“I don’t believe that Bank of Ireland was disproportionately exposed or active in the property and construction sector. I think the issue that affected the Bank of Ireland was the absolute amount in money terms of that exposure. Bank of Ireland had quite a broadly diversified loan book in its totality.”40

Brian Goggin noted that 65% of the BOI’s lending in property and construction was in investment property “generating a contracted rental flow.” He did not accept that the bank had an over-concentration of risk in the property and construction sector.41

By contrast, responding to similar a similar question regarding Project Atlas, Richie Boucher accepted that BOI had an over-concentration of risk in the property and construction sector, though he suggested that the bank believed at the time that this risk was manageable and lacked “sufficient recognition” of the connection between property markets in Ireland, the United Kingdom and the rest of the world.42

Richard Burrows, former Governor of the BOI Group, when asked by the Joint Committee to comment on how Project Atlas had highlighted problems in the BOI’s property portfolio, said:

“I think they did a forensic job at the time. It was a matter of opinion, of course, as to what value you could attribute to any particular security, because the market was effectively closed. I think they made a reasonable attempt at it.”43

Michael Fingleton, former Chief Executive, INBS noted that PwC had carried out a detailed analysis of INBS’s loan book which was positive.44

The Joint Committee was prevented by the potential of causing prejudice to the criminal proceedings from hearing evidence from several other proposed witnesses on this and other issues.

Though Project Atlas revealed a need to restructure and recapitalise the Covered Institutions, in assessing the adequacy of the Project Atlas Reports, the then Taoiseach, Brian Cowen, said the following:

“PwC was engaged to review the loan books and the capital position of the six Irish banks covered by the guarantee. The PwC report stated under a number of stress test situations that all of the Irish financial institutions which they reviewed would have sufficient capital to meet the regulatory requirements up to 2011. This analysis was hopelessly optimistic and certainly did not envisage the crisis to develop the way that it subsequently did.”45

When referred to Brian Cowen’s above assessment, Denis O’ Connor, a Partner with PwC, said that the scenario analyses were conducted “before NAMA [and] before Tier 1 Capital Ratios increased from 4% to 10%.” He also drew attention to two other factors impacting on the estimates, namely:

Aidan Walsh, Partner, PwC added that the scenarios had been examined in October 2008, which was around the time of Budget 2009. That Budget, he said, “was framed against assumptions that GDP would decline by 1% in 2009 and unemployment might rise to 7%.” However the actual values turned out to be a GDP decline of “something [like] 7%” and an unemployment rate rise of 15%. Thus, “the economic outlook in official documentation at the time was far more benign than the recession that evolved in Ireland over the subsequent two years.”47

However, insofar as the PwC analyses are concerned, two important points arise:

1. Time: With the crisis deepening, time was of the essence. Taking the time necessary to adequately interrogate each loan appears not to have been an option for PwC, as the financial institutions could have collapsed during the period, leaving the economy without a proper banking system. In this regard, Ann Nolan of the Department of Finance said:

“…we couldn’t give ourselves the luxury of taking six months to look at every single loan because the banks might have collapsed in that time, which would have left every small business in Ireland without a proper banking system.” 48

2. Management information: PwC’s work on Project Atlas was based on the management accounts of the relevant banks. Such accounts are limited in their nature as they are:

However, reliance on management information by PwC in carrying out its work seemed unavoidable.

According to the evidence of Denis O’Connor, Partner with PwC, the reports prepared by PwC did not undergo any independent verification procedures.49 The initial work was focussed on liquidity and a high level review of major lending positions and loan provisions booked by the banks.50

According to Patrick Neary: “…the professional approach taken by Pricewaterhouse … while it did rely on the banks ... questioned and interrogated the information.”51

However the situation was one where a worsening and accelerating crisis could scarcely be described, let alone quantified with certainty. A status report was urgently needed, even if it was considered inadequate.

Ann Nolan, Second Secretary, Department of Finance, described the PwC reports as the “…initial due diligence.”52 She asked whether PwC could have “known better” and indicated that she was not sure, even though the exposures eventually turned out to have been significantly understated.53 This view was reiterated by John Hurley, former Governor of the Central Bank, who said in his evidence that:

“…falling market and values were going to be determined very much in the context of the falling market, so it wouldn’t have been known at a particular moment in time how far property prices were going to go…”54

John Corrigan said that the PwC work:

“…certainly was a worthwhile exercise in that it exposed the extent to which … various developers were multi-banked, and it exposed the concentration of the system in various developers…”55

Under PwC’s scenario 2 the total impairment charges were estimated at approximately €32 billion.56 However, ultimately the State was required to invest €64.2 billion in the Irish financial institutions.57

By June, the Exchequer had estimated a tax shortfall of €3 billion for the year, while a further shortfall of €1.3 billion was evident by the end of August. As the Project Atlas loan book reviews were being conducted, the economy entered in to recession in September. The 2009 Budget, due to be announced in December 2008, was brought forward by 2 months to October 2008.58

As a result, planned pay increases for the public sector were cancelled and additional taxation measures were required to reduce the gap. Among the corrective measures announced, was the introduction of the Income Levy.

The budget was framed on the basis that tax revenues would increase by 1% in 2009, even though revenue was expected to fall by 13.7% in 2008. This growth was assumed despite GDP contracting in 2008 and the expectation that it would do so again in 2009. Increases in current expenditure were agreed, while capital expenditure was cut back.59

The Department of Finance became the driving force for discussing recapitalisation requirements with the financial institutions.60

Ann Nolan told the Inquiry:

“The PwC analysis showed clearly that there was a serious problem with land and development loans, both because of the total volume of such loans across the system and because of the small number of developers who had huge debts across the system.”61

When John Corrigan, former CEO of NTMA was questioned about AIB and BOI, he said:

“…there was extreme pushback from the two banks at the outset of these discussions…certainly they resisted the notion of recapitalisation.”62

In her evidence, Ann Nolan said that BOI was: “…most realistic…AIB told us…they didn’t need any capital…they were, you know, well able to cope.”63

In their Court64 minutes of 13 October 2008, BOI indicated that they would require a capital injection, but it was decided that it was not an opportune time to approach the Government, given the recent Guarantee decision and the Budget due to be announced the following day.65 BOI’s Court continued to discuss how they could approach the Government for taxpayer investment as a source of equity, given the tightening of liquidity and the high cost of capital they were experiencing over the period.66

In October 2008 BOI had internal discussions about the bank’s possible need for a capital injection by the State as one of a number of options reviewed by the bank at that time.

It was also noted that Brian Goggin would explore the idea of a “capital injection by the taxpayers,” but that this would not be done until after the Budget which took place around that time, mid-October. The bank’s public position at that time was that the bank did not require taxpayer funding.67

Richard Burrows said:

“In any public statement, if you’re in a situation looking for capital, the last thing you want to do is to start talking about that publicly because that just engenders a great deal of uncertainty and loss of confidence in an institution. It’s like a central banker or Minister for Finance not talking about a devaluation before he does it; he can’t because you almost make the situation worse-“He confirmed to the Joint Committee that the topic of the bank’s recapitalisation had been raised at a meeting with the Minister for Finance before the end of the year – “late autumn of 2008.”68

When asked about the board minutes, Brian Goggin said:

“the discussions around capital, as evidenced in these papers, had all to do with new capital rules arising out of the decision by the UK Government to increase the core tier 1 ratio of the UK banking system, up to 7.5%. That immediately put pressure back on the Irish banks. The capital discussions here have nothing whatsoever to do with solvency; it’s all to do with new regulatory impositions.”69

Kevin Cardiff was asked if BOI had raised the matter of requiring capital on the night of the Guarantee, given that the bank was raising it internally just two weeks after the guarantee meeting. He said, clarifying an earlier answer, that:

“the minutes you’ve sent to me talk a bit more about precautionary capital. Capital is … in a sense, they’re consistent with what I was saying last time, that at this point, there was a need for capital mostly based on changing market expectation, that they’re already saying, even on 18 October, “Look, let’s look at that.” And also, …… we and the official system started to focus on capital also almost immediately, probably around the 15th (October 2008) or so, I think, I sent an e-mail to people saying we have to now do an exercise about capital, and about whether nationalisations may be required, and so forth.”70

“having said that, I think even now they may have been a little bit coy, at the very least, because it was some months later we were still discussing with them how much capital they needed. I don’t think they were entirely upfront, let’s say, about their own desires……. if they had been more upfront about that, we might have moved along a little bit quicker.”71

When asked to comment on the position of AIB in October 2008, Eugene Sheehy, former Group Chief Executive of AIB, said:

“There’s also lots of documents you will have seen that we were adequately capitalised at the time. If a board had decided to raise funds in a share placement with customers, you would have to immediately announce that. At the time we were looking at capital, and we had a whole range of mitigants that we thought we could apply. We were a long, long way from ever having to, at that stage, ask shareholders to pay up.”72

It is clear from the board minutes of 11 December 2008, that AIB still believed that they were “…adequately capitalised…”73 and did not require any capital from the State. Dermot Gleeson told the Inquiry that he did not know when AIB became insolvent. However he referred to the fall in house prices and said: “The real trouble was 2009, and I don’t know when in 2009-10 AIB became insolvent.”74

Anglo also believed that they would raise sufficient capital. According to Gary McGann, former Non-executive Director, Anglo “…there was a belief that a recapitalised Anglo could have a future but it would need (a) stronger funding sources and (b) probably a broader funding footprint.”75

Questioned by the Joint Committee on when Gary McCann would have realised that Anglo’s future as an independent financial institution without any intervention or State support was no longer tenable, he said: “I don't think there was a point in time...at all points in time the board saw this as a funding liquidity challenge.”76 At a meeting on 12 December 2008, the board of Anglo discussed a potential mechanism for raising capital through a rights issue or a preference share issue and suggested that existing investors were prepared to participate in an equity offering.77

Recalling her first meeting with representatives from AIB and Anglo, Ann Nolan spoke of being “… stunned at the amount of capital the private sector was going to put into them.”78 However, the anticipated capital injections from private sources did not materialise for either of the two banks, as investors had lost confidence in the Irish banks.79

Throughout the month of December 2008, meetings continued between the Department of Finance, the NTMA, the Central Bank, Merrill Lynch and Arthur Cox Solicitors to discuss the recapitalisation programmes for AIB, BOI and Anglo. In his evidence, John Corrigan spoke of one particular meeting on 13 December 2008, where the NTMA, amongst others, pressed strongly for Anglo to be nationalised.80

According to Pádraig Ó Ríordáin, former Managing Partner of Arthur Cox:

“…once the State guaranteed each of the banks, then the State was, obviously, vulnerable to any default by any of the banks.”81

Accordingly, the Government made an announcement on the 14 December 2008 that the State would support the Covered Institutions through a recapitalisation programme of up to €10 billion, so as to meet with their regulatory capital requirements.82

Ultimately, the Government announced on 21 December 2008 that the State would inject €1.5 billion into Anglo and €2 billion each into AIB and BOI by way of preference shares. It was anticipated that a further €1 billion for AIB and BOI would be required83 but, according to Kevin Cardiff, the Government wanted the relevant banks to sell assets, increase profits and reduce costs to support their own levels of capital.84 Kevin Cardiff said that providing the needed capital upfront would reduce the incentive for these banks to raise additional capital on their own and that “…people didn’t want to give them that luxury.”85

Once the decision to recapitalise AIB, BOI and Anglo was made, Arthur Cox were tasked with carrying out a due diligence exercise.86

According to Ann Nolan, there were “…deep concerns about recapitalising Anglo without nationalising it, simply because of the issues that had led to the chairman’s resigning.” As a result, Arthur Cox prioritised their due diligence on that bank.87

Over the period from the end of 2008 into early 2009, two parallel work-streams continued on Anglo – one examining recapitalisation and the other nationalisation. According to Ann Nolan, the Department of Finance needed to be ready for either option once the due diligence exercise was completed. Arthur Cox, the Office of the Attorney General and the Department of Finance continued their work on the Anglo Irish Bank Corporation Bill 2009 – the legislation to nationalise Anglo. Meanwhile, the Department continued work on the recapitalisation aspect, formally notifying the European Commission on 8 January 2009.88

Arthur Cox reverted to the Department a week later on 15 January 2009, reporting on issues of legal concern within the bank.89 In addition to these issues, Anglo’s business model was considered “fatefully flawed” 90 and according to Ann Nolan, “…there was no capacity to regenerate profits, which the other banks had.” 91 As a result, a number of options in respect of Anglo had to be considered, as follows:

Due to a number of factors, including the provision of the State Guarantee, Europe’s expectation that no bank should fail93 and the likely contagion effect across the financial system, the option of the State to try to disengage from Anglo was not considered “realistic”, according to Ann Nolan.94 Having formally consulted with the Central Bank, Financial Regulator, NTMA and officials in the Department of Finance, the Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, sought a decision from the Government to take full control of Anglo by way of nationalisation and to replace the management board.95

On 15 January 2009, the Minister for Finance, on behalf of the Government, announced that Anglo would be nationalised with immediate effect. This did not increase the exposure of the State, as the State was already liable since the issue of the Guarantee in the previous September.96 However, it would appear to the Joint Committee that nationalising Anglo was carried out without the full knowledge of how much additional capital Anglo would ultimately require.

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, former Taoiseach, Brian Cowen stated that:

“…the success of the guarantee on the night was to restore liquidity that was badly needed at that critical time. It was a success for a short time and … sentiment against Irish banks continued.”97

The Guarantee did not address the on-going liquidity problems being faced by the Covered Institutions. They were still facing an extremely unstable outlook, with major withdrawals of deposits and established credit lines leading to substantial recourse to the Central Bank for short-term liquidity support.98

Consultations continued between AIB, BOI and the Department of Finance on the recapitalisations through to the end of 2008 and into early 2009. The focus was on the capital amounts required and the associated terms and conditions.99

In February 2009, the Government agreed a Core Tier 1 capital injection of €3.5 billion for both AIB and BOI through a proposed purchase of preference shares by the National Pension Reserve Fund (NPRF).100 BOI advised members of their Court on 18 March 2009 that they needed additional capital and the only available source was the Government.101 According to Michael Somers, former CEO of the NTMA, the NTMA became involved because it had the cash from the National Pension Reserve Fund (NPRF) and the Government wanted the agency to invest it in the banks.102

Certain conditions were attached to the recapitalisations, such as:

However in March 2009, while carrying out a legal and financial due diligence exercise on both institutions108 the NPRF wrote to the Minister for Finance advising him that “…it is likely that the proposed €3.5bn preference share investment in AIB will fall short of what is required.”109

It appeared to the NTMA that AIB felt its position was no worse than that of BOI and that AIB would only recommend to their shareholders an amount of additional capital that was equal to the amount to be provided to BOI.110 It was agreed, ultimately, that AIB would sell their US and Polish subsidiaries to cover the shortfall and a capital injection of €3.5 billion was reaffirmed.111 The sale of the Polish subsidiary did not occur until early 2010, after the Central Bank had completed the PCAR (Prudential Capital Assessment Review) and “…insisted that the assets be sold…”112

Meanwhile, Anglo continued to struggle post-nationalisation. The market had lost confidence in the bank and the new management board could not curtail its deteriorating capital position.113 As Ann Nolan commented: “… Anglo surprised on the downside every time you looked at it for the entire period … and that’s just looking at the losses.”114

In its December 2008 monthly accounts, Anglo’s Core Tier 1 Capital Ratio stood at 5.7%. By February 2009, this had fallen to 4.9%. In effect, Anglo had only €790 million of capital to absorb any further losses on their loan book before they would be in breach of their 4% regulatory capital requirement.115 The business model was broken and did not facilitate a source of income to make up the additional capital that the bank urgently required.116

According to Kevin Cardiff, Anglo “…was never going to get all of the capital it might want upfront.”117 Consequently, capital injections were phased: in June 2009 the Minister for Finance invested €3 billion and a further €1 billion was invested in August 2009.118

While the NTMA was reluctant to use the NPRF to recapitalise AIB and BOI, this went ahead on the Minister for Finance’s instruction.119 John Corrigan said that it was considered that “…there was a strong probability that the State would get its money back…” from BOI and AIB, but it was believed to be unlikely that the money would be recouped from Anglo. For this reason, the recapitalisation of Anglo was made using cash drawn from the Exchequer rather than the NPRF.120

Problems arose for the State authorities such as the Department of Finance and the NTMA when seeking to estimate the projected scale and timing of bank recapitalisations. On the basis of evidence presented to the Inquiry, these problems arose from the following factors:

1. Declining asset values: Officials did not foresee the extent of the future drop in asset values. The drop in values reached up to 50% for housing121 and around 90% for non-developed land.122

2. Reliance on management information: PwC were engaged to review the loan books and capital positions of the Covered institutions. However, as previously discussed, though PwC’s work expanded over time, it was based predominantly on the management accounts of the Covered Institutions and did not involve any independent verification. The Joint Committee is of the view, such work should have been commissioned.123

3. Non-performing loans: The extent of non-performing large commercial loans, especially land and property related, was not known prior to their transfer to NAMA in 2010. It transpired ultimately that only 23% of the property-related loans transferred to NAMA were in actual fact performing, which was close to only half of the NAMA Participating Institutions’ own estimates. Furthermore, there were significant variances between those institutions. 124 That exerted a major influence on the scale and timing of the recapitalisations of individual institutions.

The unknown scale of the above together with other poor lending practices, interest roll-up and reliance on paper equity made projections on bank recapitalisations difficult to estimate in a volatile market. This eventually necessitated the engagement of Blackrock Solutions to assess and model bank portfolios in 2010 and 2011, through the PCAR and PLAR exercises.125

In tandem with the capital injections into AIB and BOI, the economic situation continued to deteriorate. The Government felt it necessary to introduce further fiscal adjustments, in the form of a “mini-budget”, in April 2009. A review of Exchequer revenue and expenditure revealed that the expected General Government Deficit as a percentage of GDP had only reduced to 10.75%.126 In October 2008, the Government planned to reduce this to a 6.5% deficit.1

When the “mini-budget” was introduced, the Exchequer borrowing requirement was forecast to be €20.3 billion.1 In reality, the borrowing requirement exceeded the forecast considerably, rising to €24.6 billion by the end of 2009.127 Overall, expenditure cuts of €1.5 billion and tax increases of €1.8 billion were introduced.128

This 2009 “mini-budget” also included significant institutional changes, most notably the creation of NAMA129 and the reform of the Central Bank.130

In October 2009, a Memorandum for Government indicated that the Government was considering a number of options for restructuring the banks. These included a possible merger of EBS and INBS and a possible sale of the combined entity to IL&P; the possibility of either Ulster Bank or Bank of Scotland Ireland taking over the combined EBS/INBS entity and the acquisition by a foreign institution of EBS/INBS.133

Each of the Covered Institutions was required to prepare and submit a 3-year business and recovery plan to the Central Bank setting out how management intended to return the relevant Covered Institution to a stable, properly capitalised and profitable position. The plans would also have to be approved by the European Commission and monitored on a quarterly basis.134

Ultimately, the merger of EBS and INBS did not proceed. The Government decided to merge EBS with AIB as it failed to get sufficiently attractive bids to sell EBS.135 Anglo and INBS were deemed to be non-viable and, therefore, a specific plan was put in place for these two institutions.136 They ultimately became Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC).137

The preparation, approval and re-approval of these plans took from 2009 to 2013, with BOI’s plan approved quickly under State aid rules and AIB’s plan taking longer, due the merger of AIB and EBS. However, PTSB’s plan was not approved until April 2015, as their restructuring proved slower than the other banks. Each of the banks produced several iterations of their plan over the period, as the economic environment continued to deteriorate and their capital requirements grew due to their increasing loan provisions.138

Between the announcement of the Government’s Guarantee in September 2008 and completion of the first bank recapitalisation programme by the end of 2009, a number of significant changes unfolded as the financial institutions and official bodies adjusted to the new banking environment.

One of the first changes insisted upon by the Government as a condition of the Bank Guarantee was the appointment of Government nominated Non-Executive Directors to the boards of the Covered Institutions. Often referred to as Public Interest Directors, the reasons for their appointment were explained to the Inquiry by the former Taoiseach, Brian Cowen:

“Well public interest directors were ... the idea there was that whilst we didn’t have ownership of these banks, we believed this was in the interest ... to try and help restore some public confidence in the governance of these organisations to have people who are in there.... they would be au fait with Government policy or public policy and would be bringing that perspective to the table while others from the private sector expertise might be bringing a commercial experience to it. It was a balance if you like, to try and ... to demonstrate (a) that it was important that there be public interest directors and (b) that they would be capable of ensuring that at board level people understood what the public policy priorities of Government would be in respect of how they were conducting their business.”139

Alan Dukes, when asked about his role as a Public Interest Director for Anglo, stated:

“…you had a duty to the company and … you had a duty to the shareholder and … you had a duty of care to the employees of the company and you still had to bear the public interest in mind. But where all these things met was never clear.”140

He went on to say:

“I rationalised it to myself on the basis that I was there to look after the public interest, the shareholder in the bank was the Minister for Finance. The Minister for Finance has a duty to the public interest and in a sense kind of embodies the public interest, so the objectives of the Minister for Finance satisfied the requirements that I look after the public interest.”141

The Minister for Finance nominated 12 Public Interest Directors, two directors to the board of each of the Covered Institutions.142 These appointments, made in January 2009, were the first of many leadership changes across the six Covered Institutions. During 2009, AIB’s Chief Executive, Chair and Group Finance Director retired,143 while BOI’s Governor chose not to stand for re-election and the BOI Group CEO stepped down.144 IL&P accepted resignations from their CEO and CFO.145 INBS also lost its Chairman and Chief Executive,146 while EBS saw its Chief Financial Officer depart alongside the Managing Director of its Haven Mortgages subsidiary.147 Numerous other non-executives and other members of senior management teams departed posts across the Irish banks during the year.

On the regulatory side, publication of the Central Bank’s 2008 Financial Stability Report, was delayed due to market uncertainty. Initially scheduled for publication in November 2008, it was eventually decided in February 2009 that the report would never be published.148

There were also changes of key personnel within the Central Bank. Although it was announced in January 2009 that John Hurley would be reappointed for a second seven year term as Central Bank Governor, he had indicated to the Minister for Finance that he would not serve for more than one year and subsequently retired in September 2009, when he was succeeded by Patrick Honohan.149

At the Financial Regulator, its Chief Executive, Patrick Neary, retired in January 2009150 and his role was taken over on an interim basis by the Financial Regulator’s Consumer Director, Mary O’Dea.151 This interim appointment was eventually extended until January 2010, when Matthew Elderfield arrived from his post as Chief Executive of the Bermuda Monetary Authority,152 following an extensive international search.

By the time of Matthew Elderfield’s appointment, the Central Bank and Financial Regulator had already begun to implement an extensive programme of reforms, driven by both national and international responses to the financial crisis. The report considers these reforms in more detail at Appendices 10 and 11.

The ELG Scheme153 was introduced in December 2009 and ran in tandem with the Credit Institutions (Financial Support) Act 2008 (CIFS Act 2008) until September 2010. The CIFS Act 2008 guaranteed the liabilities of the Covered Institutions until end September 2010.154 The ELG Scheme provided for an unconditional and irrevocable State Guarantee for certain eligible liabilities (including deposits) of up to five years in maturity incurred by the financial institutions from the date they joined the Scheme until the closure of the Scheme, subject to certain terms and conditions. The NTMA was appointed by the Minister for Finance as the ELG Scheme Operator.

On 26 February 2013 the Minister for Finance announced the closure of the ELG Scheme to all new liabilities from 28 March 2013. After this date, no new liabilities would be guaranteed under the Scheme. This did not affect any liabilities already guaranteed as of 28 March 2013.155

In early 2010, the Central Bank carried out a review of the Covered Institutions’ capital positions. This Prudential Capital Adequacy Review (PCAR)156 exercise identified a need for approximately a further €10.9 billion157 of capital to be provided for AIB, Bank of Ireland and EBS combined.158

In giving evidence to the Inquiry, former Group Chief Executive of the EBS, Fergus Murphy said:

“EBS actually grew its retail deposits by circa €2 billion through the crisis, a notable feat when compared with the exodus of retail deposits from other institutions during this period. This particular action helped to stabilise the society and along with the actions on exiting commercial property and land and development finance and other actions, lessened the ultimate amount of capital that the organisation eventually required.”159

BOI met their requirement for €2.66 billion additional capital by raising new capital in the market and by converting €1.7 billion of their existing €3.5 billion preference shares into ordinary shares. AIB sold its Polish operations and its investment in M&T Bank in the US, which contributed €3.4 billion of its capital requirement. The Government provided the balance of €4 billion.160

In September 2010, due to the increasing scale of discounts being applied to loans on being transferred to NAMA, the Central Bank determined that AIB would require a further €3 billion of capital over and above the €7.4 billion capital injection which had occurred in March 2010.161 This figure was rolled-up into the revised capital requirements arising from the PCAR/PLAR 2011 exercise.162

Anglo and INBS were not formally part of the initial PCAR exercise in 2010, due to the fact that a final decision had not been taken on the restructuring of either institution. However the Central Bank did give an indication in its PCAR announcement in March 2010 that, as an interim measure, Anglo would require €8.3 billion of additional capital and that INBS would need €2.6 billion.163 These requirements were satisfied by the issuance of a Promissory Note at the end of March 2010.164 The quantum of this Promissory Note was increased on several occasions during 2010 as the extent of the final haircuts applied by NAMA to loans transferred from both Anglo and INBS became clearer.165 Ultimately, the value of the Promissory Notes issued by the Government in support of Anglo and INBS reached €30.6 billion by the end of 2010.166

The Government’s initial intention regarding the restructure of Anglo was to remould it into a new business bank. However, in 2009, Anglo made a loss of €12.7 billion. In 2010 it made a loss of almost €17.7 billion. The 2010 figures were partly driven by haircuts applied to NAMA loans, which amounted to €11.5 billion.167 This, together with the severity of the Irish sovereign debt crisis and the additional capital required by Anglo, meant that the funding of any future business was likely to be challenging.168 Hence, this plan was quickly abandoned in favour of splitting Anglo into an asset recovery vehicle and a funding bank.169 A Restructuring Plan based on this approach was submitted to the European Commission on 22 October 2010.170

The Government had initially provided INBS with €2.7 billion to cover losses arising on its commercial property loan portfolio.171 In September 2010, the NTMA recommended that a further €2.7 billion be provided to cover expected losses on the residual (post-NAMA transfer) loan book.172 In evidence to the Inquiry, Michael Fingleton, Michael Walsh and John Stanley Purcell all indicated that they believed that the discounts applied by NAMA for their loans were excessive and that this led to INBS requiring more additional capital than they felt was required.173 INBS had ceased to function as a lending institution and the Government was formulating proposals as to the future of the business. The Restructuring Plan for INBS had been submitted to the European Commission in June 2010 and it proposed “the continued management of the society as a going concern in anticipation of a sale to a trade buyer.”174

The entry into the Bailout Programme and the subsequent negotiations with the Troika on the restructuring and future of the Irish banking system had a significant impact on the future of Anglo and INBS. See Chapter 10 – The Troika Programme.

A revised Joint Restructuring Plan was submitted to the EU in January 2011.175 This plan provided for the sale of the deposit franchises of both Anglo and INBS, the management of the residential mortgage portfolio (ex-INBS) for eventual sale and the orderly wind-down of the combined commercial loan book over a 10 year period.176 The combined entity would not require any further capital injections from the State. The Joint Restructuring Plan was approved by the European Commission in June 2011.177 Anglo and INBS were merged into one entity in July 2011, to form IBRC and IBRC’s executive management team focused on delivery of the agreed strategy.178

In his evidence, Pádraig Ó Ríordáin explained the use of Promissory Notes during the relevant period:

“Promissory notes constituted promises to pay an amount over time to the bank but were accounted for as capital as if they had been paid in cash. However, accounting rules required that they carry a high coupon or interest rate to be paid by the State. The banks then pledged the promissory notes as collateral with the Central Bank, which in return provided the banks with cash in the form of emergency liquidity assistance (ELA).”179

By the end of 2010, the State had provided capital of €34.7 billion in support of Anglo and INBS (IBRC), of which €30.6 billion was made up of Promissory Notes.180 In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Pádraig Ó Ríordáin said:

“It became a central objective of both the Government and the Central Bank to unwind this arrangement as the cost of the promissory notes to the Government was very high and the ECB/Central Bank wished to wean the Irish banks off ELA.”181

These Promissory Notes required a payment to be made to the Central Bank of €3.1 billion in March each year.182 At the time, IBRC was reliant on Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) from the Central Bank of circa €41 billion and, in the absence of an alternative funding solution from the ECB, it was imperative that IBRC retained its banking licence and access to ELA.183 According to Michael Noonan:

“…maintaining Central Bank funding to support the wind-down of IBRC was the most prudent approach to protect the taxpayer. Various alternative sources of long term funding were explored but did not prove possible. It was only when a long-term viable solution for the promissory notes was found and the system more generally had stabilised, that we decided to liquidate the bank.”184

In early February 2013, pursuant to section 3(3) of the Anglo Irish Bank Corporation Act 2009, Kieran Wallace and Eamonn Richardson of KPMG were appointed by the Minister for Finance as Special Liquidators to IBRC.185 By doing so, this “…triggered events of default under a range of agreements between IBRC, the CBI and third parties.”186 According to Michael Noonan, this involved:

“…the winding down of its business operations, discharging the liability of IBRC to the Central Bank in a way that ensured no capital loss for the Central Bank, while the remaining loans of IBRC would be sold on the market or, if necessary, transferred to NAMA and, finally, converting the IBRC promissory note to a portfolio of fully marketable long-term Irish Government bonds. Through these actions the promissory notes and IBRC were to be eliminated from the Irish financial landscape with consequent reputational benefits.”187

The Joint Special Liquidators now controlled the operations of the IBRC pursuant to the IBRC Act 2013.188

Ireland’s entry into the Troika Bailout Programme in November 2010 (see Chapter 10 The Troika Programme) had two core elements: one relating to fiscal policy and structural reform and the other relating to bank restructuring and reorganisation.189 Regarding the latter, a plan called the Financial Measures Programme (FMP) was developed. This provided for a fundamental downsizing and reorganisation of the banking sector and the recapitalisation of the Covered Institutions to the highest international standards.190

The FMP was announced on 31 March 2011 and its main elements were:191

In the view of Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General at the Department of Finance, this programme marked “a key turning point in the rescue of the Irish banking system.”192

As part of the FMP, the Central Bank undertook a further PCAR exercise in March 2011.193 This exercise identified a need for the banks to raise a further €24 billion of capital. The exercise also included a Prudential Liquidity Assessment Review (PLAR) which was used to identify the amounts of assets required to be disposed of by the banks to aid their return to stable funding levels.194

The aggregate target for disposals agreed with the Central Bank was some €72 billion over the 3 year period 2011 to 2013.195

PCAR identified the need for additional capital of €24 billion, over and above the €46.3 billion that had already been invested by the State up to the end of 2010.

As part of this capital raising exercise, AIB,196 BOI and PTSB197 were required to undertake Liability Management Exercises (LME) which, in practice, meant buying back their subordinated debt from investors at a discount to the original face value. This “burden sharing”

exercise in 2011 generated €5.198 billion of the additional capital required and reduced the State’s funding requirement by that amount.198 See Chapter 11 – Burden Sharing. Nonetheless, the State was still required to inject a further €16.6 billion199 into Irish banks, including €3 billion of contingent capital,200 as set out below:

| AIB | EBS | AIB & EBS | BOI | PTSB | Total | |

|

Gross capital required pre buffer |

10.5 |

1.2 |

11.7 |

3.7 |

3.3 |

18.7 |

|

Buffer (equity) |

1.4 |

0.1 |

1.5 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

2.3 |

|

Equity capital requirement |

11.9 |

1.3 |

13.2 |

4.2 |

3.6 |

21.0 |

|

Buffer CoCo |

1.4 |

0.2 |

1.6 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

3.0 |

|

Total capital requirement |

13.3 |

1.5 |

14.8 |

5.2 |

4.0 |

24.0 |

|

Capital raised: |

||||||

|

Private equity raising** |

0.0 |

2.3 |

0.0 |

2.3 |

||

|

Liability management exercises |

2.1 |

1.7 |

1.0 |

4.8 |

||

|

Other |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

||

|

Government capital injection |

11.1 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

13.6 |

||

|

Equity capital |

13.2 |

4.2 |

3.6 |

21.0 |

||

|

CoCo |

1.6 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

3.0 |

||

|

Total capital |

14.8 |

5.2 |

4.0 |

24.0 |

||

| ** Includes debt for equity swaps | ||||||

Source: PCAR 2011 Review201

As part of the PCAR 2011 exercise, PTSB were required to sell off its Irish Life business, which it eventually did in February 2013. The sale raised €1.3 billion, resulting in a reduction the State’s ultimate contribution.202

Overall, on completion of the 2011 capital raising exercise, the State had provided the Irish banks with a total of €64.2 billion in the 3 years since a decision was first made to provide capital in December 2008. A summary of the total investment by the State in the Irish banks is set out in the table below.

| Details of the State's investment | ||||||

|

Domestic Bank Recapitalisation |

AIB/EBS €' bn |

BOI €' bn |

IL&P €' bn |

IBRC €' bn |

Total €' bn |

% of GDP** |

|

Pre-PCAR 2011: |

||||||

|

Government Preference Shares (2009) - NPRF |

3.5 |

3.5* |

7 |

4% |

||

|

Ordinary Share Capital (2009) - Exchequer |

4.0 |

4 |

3% |

|||

|

Promissory Notes {2010) |

0.3 |

30.6 |

30.9 |

20% |

||

|

Special Investment Shares {2010) - Exchequer |

0.6 |

0.1 |

0.7 |

0% |

||

|

Ordinary Share Capital (2010)- NPRF |

3.7 |

3.7 |

2% |

|||

|

Total pre-PCAR 2011 |

8.1 |

3.5 |

0 |

34.7 |

46.3 |

30% |

|

PCAR 2011: |

0 |

|||||

|

Capital from Exchequer |

3.9 |

2.7 |

6.6 |

4% |

||

|

NPRF Capital |

8.8 |

1.2 |

10 |

6% |

||

|

Total PCAR 2011 |

12.7 |

1.2 |

2.7 |

0 |

16.6 |

11% |

|

Purchase of Irish Life |

1.3 |

1.3 |

||||

|

Total Recapitalisation from the State |

20.8 |

4.7 |

4 |

34.7 |

64.2 |

41% |

|

Source of Funds: |

||||||

|

Promissory Notes |

0.3 |

30.6 |

30.9 |

20% |

||

|

Exchequer |

4.5 |

4.0 |

4.1 |

12.6 |

8% |

|

|

NPRF |

16.0 |

4.7 |

20.7 |

13% |

||

|

Total |

20.8 |

4.7 |

4.0 |

34.7 |

64.2 |

|

Source: Department of Finance report for Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015203

The deleveraging plan was successfully completed by the target date. The banks sold €45 billion worth of assets over the period of the plan through amortisation and the disposal of bank assets.204

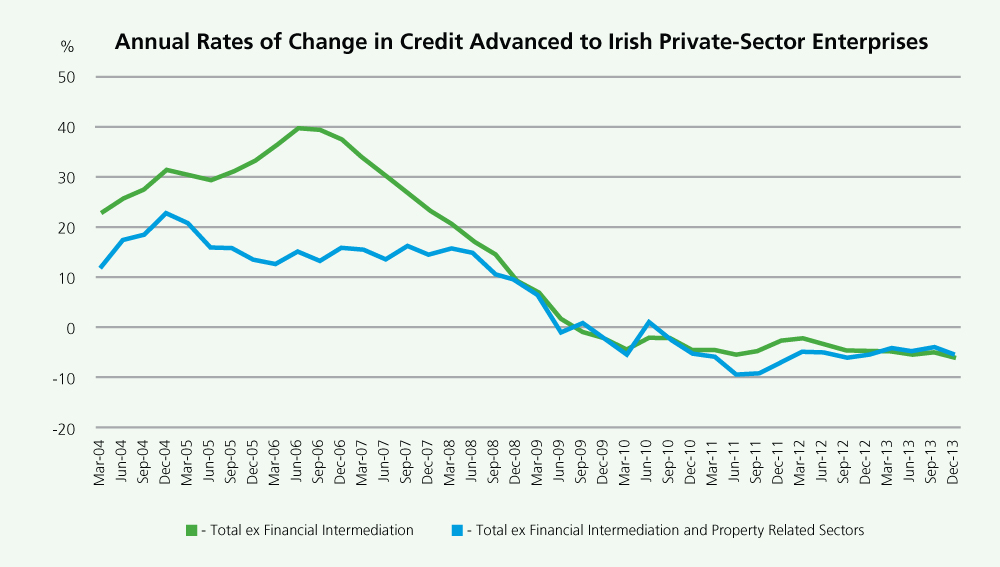

One consequence of the crisis and the ensuing bank restructuring efforts was the almost total cessation of new lending for businesses of all sizes over the period 2009 to 2013.205

Despite specific provisions in the restructuring plans of both BOI and AIB for boosting credit availability to the business sector, both supply and demand for credit remained depressed, partly due to the recession and also due to the structural constraints under which the banks were operating.206 These constraints included the need to restore the banks’ capital ratios, a focus on asset recovery and disposal, liquidity constraints and a reduced appetite to take risk.207

The following graph depicts the percentage change in new lending to Irish private sector businesses over the period from 2001 to 2013.

Source: Central Bank of Ireland: Trends in Business Credit and Deposits208

NAMA acquired loans from the Participating Institutions valued at €74.4 billion.209 Taking account of discounts applied, the Participating Institutions ultimately reduced their balance sheets by around €70 billion (which was equivalent to 45% of GDP)210 in line with the deleveraging targets set out as part of the Troika monitoring programme. The objective, as described by Brian Cowen, was to get “…a situation going as quickly as possible where banks could show repaired balance sheets and get on with lending...”211

When the large property-related loans were transferred from the Participating Institutions to NAMA in 2010, residential property prices were still plunging. House prices reached their peak in September 2007 and their lowest point in March 2013.212 The difference amounts to a fall of 51%.213

The decline in asset values, combined with high loan-to-value ratios in lending during the later stages of the boom years, resulted in many of the remaining loans in the financial institutions also being highly leveraged.

Dirk Schoenmaker, Professor of Banking and Finance at the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam, commented as follows in an academic paper:

“…While in 2005, only half of first time buyers had LTV rates above 90 per cent, with very few above 100 per cent, these numbers went up in 2005 and 2006. By then, two-thirds of mortgages to first time buyers had LTV rates over 90 per cent and one third over 100 per cent …”214

The table below illustrates the volume of property loans which still remained on the Covered Institutions’ balance sheets at the end of December 2013.

| Outstanding loans | Impaired loans | |||||

|

BOI |

AIB |

PTSB |

Total |

Impairment rate |

Impairment loans |

|

|

Mortgages |

51.6 |

40.7 |

29.0 |

121.3 |

17.7% |

21.5 |

|

CRE |

16.8 |

19.7 |

36.5 |

56.9% |

20.8 |

|

|

SME |

13.6 |

13.7 |

27.3 |

25.1% |

6.9 |

|

|

Corporate |

7.8 |

4.3 |

12.1 |

25.1% |

3.0 |

|

|

Consumer |

2.8 |

4.3 |

0.3 |

7.4 |

6.1% |

0.4 |

|

Total |

92.6 |

82.7 |

29.3 |

204.6 |

25.7% |

52.6 |

|

Note: Source: |

||||||

Source: Schoenmaker215

At the end of 2013, two-thirds of all property-related loans remained on the balance sheets of the Covered Institutions and €42.3 billion worth of these were impaired loans (i.e. 17.7% of mortgages and 56.9% of CRE). That debt still existed even though, as already noted, €74 billion of property-related loans (referred to as CRE in the table above) had already been transferred from banks and into NAMA.

Whilst the Irish banks have taken large provisions for non-performing loans (53% as at June 2014), the level of actual loan write offs at 5.2% could be considered quite low.216

In his paper, Dirk Schoenmaker captures the lack of execution of the strategy. He states:

“Taking sufficient provisions for NPLs [non-performing loans] is a first step to heal banks. A necessary second step is to write off bad loans, to clean up bank balance sheets. On the first step, Ireland has been pro-active. On the second, progress is very slow…”217

Economist, Peter Bacon commented in his evidence:

“If there were a [further] Bacon report, what would it be focusing on at the moment? It would be saying, “Why in heaven’s name, seven or eight years after the collapse, are we still dealing with a mortgage arrears problem?”218

During 2010 – 2012, Covered Institutions could only go to the markets with government-guaranteed CIF or ELG bonds. It was not until November 2012 that the Pillar Banks were in a position to return to the markets on a standalone basis.

BOI moved first with an unguaranteed 3 year, €1 billion, Asset Covered Security (ACS) bond219 (also known as a Covered Bond) on 13 November 2012. AIB followed suit with an ACS issuance of €500 million the following month. In December 2012, BOI managed to raise €250 million in the first subordinated bond issue deal with a 10% coupon220 and a maturity of 10 years in a targeted deal for their equity investors.221

Over the next year, the two Pillar Banks were set to issue more ACS Bonds and subordinated bonds but it took until 29 May 2013 before BOI went to the market with a senior unsecured and fully unguaranteed bond. BOI launched an unsecured bond for €500 million, which was oversubscribed.222

AIB were able to carry out a similar transaction in November 2013, which was also oversubscribed.223

| Recent bond issuance by the Irish 'Pillar Banks' | ||||

|

Announcement date |

Issuer |

Description |

ISIN |

Amount issued |

|

13/11/2012 |

BKIR |

3 Year ACS |

XS0856562524 |

€1,000m |

|

28/11/2012 |

AIB |

3 Year ACS |

XS0861589819 |

€500m |

|

12/12/2012 |

BKIR |

10 Year T2 debt |

XS0867469305 |

€250m |

|

22/01/2013 |

AIB |

3.5 Year ACS |

XS0880288211 |

€500m |

|

15/03/2013 |

BKIR |

5 Year ACS |

XS0907907140 |

€500m |

|

29/05/2013 |

BKIR |

3 Year senior unsecured |

XS0940658361 |

€500m |

|

03/09/2013 |

AIB |

5 Year ACS |

XS0969616779 |

€500m |

|

25/09/2013 |

BKIR |

7 Year ACS |

XS0975903112 |

€500m |

|

31/10/2013 |

BKIR |

12 Year ACS (private placement) |

XS0991249623 |

€10m |

|

06/11/2013 |

BKIR |

3.5 Year ACS |

XS0993264331 |

€1,000m |

|

19/11/2013 |

AIB |

3 Year senior unsecured |

XS0997144505 |

€500m |

|

(‘BKIR’ referred to in the table above is Bank of Ireland) |

||||

Source: Recent bond issuance by the Irish “Pillar Banks”224

This AIB transaction took the total bond issuance by the two Pillar Banks in 12 months to just over €5.7 billion with public transactions going out as far as 10 years.

AIB and BOI were now back in the international debt markets without the need for a support line from the State for the first time since the introduction of the Guarantee.

In June 2012, the European Heads of State decided to “…break the vicious circle between banks and sovereigns, and that when a Single Supervisory Mechanism is in place involving the ECB, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) could recapitalise banks directly.”225

The possibility of retroactive recapitalisation will also be available to Irish financial institutions, through a specific provision in the ESM.226 According to Michael Noonan: “…ESM may directly recapitalise banks or retroactively recapitalise banks. But it needs unanimity of the governors and it has to be done on a case-by-case basis…”227 (See Appendix 10 for further detail on SSM and ESM)

The reasons that PwC’s Project Atlas Report (September/October 2008) did not reveal the true extent of the capital requirements of the banks were:

Chapter 8 Footnotes

1. Letter from the Financial Regulator to all Covered Institutions, Q4 2008, INQ00166-001, (Subject to S33AK, Central Bank Act 1942).

2. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, ANO00002-001.

3. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00089-114.

4. Cormac McCarthy, former CEO, UB, transcript, INQ00086-048.

5. RBS Group Annual Report and Accounts 2008, page 29: http://www.investors.rbs.com/~/media/Files/R/RBS-IR/annual-reports/rbs-group-accounts-2008.pdf

6. RBS Group Annual Report and Accounts 2008, page 104: http://www.investors.rbs.com/~/media/Files/R/RBS-IR/annual-reports/rbs-group-accounts-2008.pdf

7. RBS Group Annual Report and Accounts 2008, page 148: http://www.investors.rbs.com/~/media/Files/R/RBS-IR/annual-reports/rbs-group-accounts-2008.pdf

8. Richie Boucher, Group CEO, BOI, transcript, INQ00085-038.

9. Project Atlas was a PwC report on the health of the Irish banking system, commissioned by the Financial Regulator in 2008.

10. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2008/si/411/made/en/print

11. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-079.

12. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, transcript, INQ00110-028.

13. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2008/act/18/section/8/enacted/en/html#sec8

14. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, transcript, INQ00110-041.

15. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, transcript, INQ00110-041; The Credit Institutions (Eligible Liabilities Guarantee Scheme) 2009 in made pursuant section 6 (4) of the Credit Institutions (Financial Support) Act 2008 and came into effect on the 9 September 2009.

16. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00273-009.

17. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic & Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-019.

18. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-020.

19. Patrick Neary, former CEO and former Prudential Director, IFSRA, transcript, INQ00132-080.

20. Merrill Lynch Wealth Management memo, NTMA00399-002.

21. Statement by An Taoiseach, Brian Cowen, 30 September 2008, DOT00164-005.

22. Government announcement on maintaining capital levels in the Covered Institutions, 30 November 2008, PUB00288-001.

23. Government announcement on maintaining capital levels in the Covered Institutions, 30 November 2008, PUB00288-001.

24. As PwC had completed a lot of the necessary background work, the firm was engaged to carry out further reviews, as required.

25. Allied Irish Banks plc, Anglo Irish Bank Corporation plc, Bank of Ireland Group, Educational Building Society, Irish Life & Permanent plc, Irish Nationwide Building Society.

26. Denis O’Connor, Partner, PwC, statement, DOC00001-006.

27. Denis O’Connor, Partner, PwC, statement, DOC00001-006.

28. See Glossary of Terms.

29. See impairment levels in terms of basis points contained within Project Atlas II Volume 1 Overview Working Draft, 17 November 2008, DOF02573-090, (e.g. Commercial/Corporate impairment of 150bps in scenario 1 and 125 bps in scenario 2 – equates to 4.5%/3.75% impairment over 3 years when asset values had already fallen in excess of this since the beginning of 2008).

30. Jones Lang LaSalle valuations were completed over the period November/December 2008.

31. Irish Life & Permanent plc was not included in the Jones Lang LaSalle valuations of land and development loans, as they did not lend to this part of the property sector; Project Atlas, Draft Property Values Review, 4 February 2009, DOF05792-013.

32. Project Atlas, Draft Property Values Review, 4 February 2009, DOF05792-013.

33. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-028.

34. Merrill Lynch and PwC summary, DOF03984-002.

35. Michael Somers, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00093-021.

36. Denis O’Connor, Partner, PwC, transcript, INQ00097-003.

37. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-028.

38. David Doyle, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00113-036.

39. Patrick Neary, former CEO and former Prudential Director, IFSRA, transcript, INQ00132-074.

40. Brian Goggin, former Group CEO, BOI, transcript, INQ00139-005.

41. Brian Goggin, former Group CEO, BOI, transcript, INQ00139-006.

42. Richie Boucher, Group CEO, BOI, transcript, INQ00085-015.

43. Richard Burrows, former Governor, BOI, transcript, INQ00104-045.

44. Michael Fingleton, former CEO, INBS, statement, MFI00001-013.

45. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister for Finance, statement, BCO00002-005.

46. Denis O’Connor, Partner, PwC, transcript, INQ00097-008.

47. Aidan Walsh, Partner, PwC, transcript, INQ00097-008.

48. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-016/017.

49. Denis O’Connor, Partner, PwC, transcript, INQ00097-034.

50. Also referred to as an Impairment provision, this is an amount set aside from profits to cover the expected loss on a loan that is impaired.

51. Patrick Neary, former CEO and former Prudential Director, IFSRA, transcript, INQ00132-110.

52. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-016.

53. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-021.

54. John Hurley, former Governor, Central Bank, transcript, INQ00047-118.

55. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-028.

56. Jones Lang LaSalle summary, DOF04897-004.

57. Department of Finance report for Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015, DOF07852-003.

58. Oral PQ, 25 September 2008, DOF07613-003/004.

59. Budget 2009: An Assessment for CBFSAI, Q4 2008, CB-Narrative INQ00167-001.

60. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, ANO00002-002; John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, also advised the Joint Committee that in the case of the first round of recapitalisations “the Central Bank really wasn’t involved”, transcript, INQ00106-014.

61. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-002.

62. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-033.

63. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-034. This is also supported by Eugene Sheehy, former Group Chief Executive, AIB, where he confirms saying AIB would rather die than take equity in October 2008, transcript, INQ00133-012.

64. Bank of Ireland’s board is known as the “Court.”

65. BOI Court minute 13 October 2008, BOI03889-002.

66. BOI Court minute 17 October 2008, BOI04042-004.

67. BOI Court Minute Extract 17 October 2008, BOI04042-004.

68. Richard Burrows, former Governor, BOI, transcript, INQ00104-060.

69. Brian Goggin, former Group CEO, BOI, transcript, INQ00139-063.

70. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-030.

71. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-030/031.

72. Eugene Sheehy, former Group CEO, AIB, transcript, INQ00133-012.

73. AIB Board minute 11 December 2008, AIB02517-002.

74. Dermot Gleeson, former Chairman, AIB, transcript, INQ00123-010.

75. Gary McGann, former Independent Non-executive Director, Anglo, transcript, INQ00082-024.

76. Gary McGann, former Independent Non-executive Director, Anglo, transcript, INQ00082-024.

77. Anglo Board Minute, 12 December 2008, IBRC00626-001.

78. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-034.

79. David Doyle, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, DDO00001-011.

80. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript INQ00106-003; Minutes of sub-group meetings, 13 December 2008, DOF04995-001.

81. Pádraig Ó Ríordáin, Partner, Arthur Cox, transcript, INQ00111-014.

82. Government announcement on €10bn recapitalisation of Covered Institutions, 14 December 2008, DOF00752-001.

83. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-019.

84. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-035.

85. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-035.

86. Pádraig Ó Ríordáin, Partner, Arthur Cox, statement, POR00001-006; Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-003. Due to legal privilege, little detail is held on the scope of this exercise.

87. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-013.

88. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-013.

89. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-038.

90. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-010. This is reiterated by Pádraig Ó Ríordáin, Partner, Arthur Cox, transcript, INQ00111-018/019.

91. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-038.

92. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-003.

93. John Hurley, former Governor, Central Bank, transcript, INQ00047-077 to 079.

94. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-003.

95. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-003. Memo for Government decision on Nationalisation, 15 January 2009, DOF02259-001.

96. Pádraig Ó Ríordáin, Partner, Arthur Cox, transcript, INQ00111-020.

97. Brian Cowen, former Taoiseach and Minister, transcript, INQ00089-114.

98. Memo to Government on a proposal for a NAMA, March 2009, DOF03553-001.

99. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-003.

100. Memo for Government – Recapitalisation of the Banking System, 11 February 2009, DOF07683-001.

101. Memo to BOI Court, 18 March 2009, BOI04068-003.

102. Michael Somers, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00093-022.

103. Memo for Government, 11 February 2009, DOF07683-002.

104. Memo for Government, 11 February 2009, DOF07683-002.

105. See Glossary of Terms.

106. Memo for Government, 11 February 2009, DOF07683-006.

107. Memo for Government, 11 February 2009, DOF07683-005/006.

108. This was due diligence exercise undertaken by PwC and Arthur Cox.