Back to Chapter 10: Ireland and the Troika Programme

Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General, Department of Finance, described “burden-sharing” to the Joint Committee as:

“…bondholders [would have] received less than the face value, of their loans to the Irish banks, thus ensuring an improvement in the balance sheet position of the banks (if they don’t have to repay so much, their liabilities are reduced) and in turn reducing the cost to the Irish taxpayer of saving the banks. So the idea is that some of the losses of the banks are forced back onto the investors in bank bonds.”1

A central question that the Joint Committee considered was whether or not the financial burden of recapitalising and restructuring the banking system following the Guarantee decision could and should have been shared with holders of senior bonds in the Covered Institutions.

Such a move was not necessarily straightforward and, ultimately, losses were not imposed on senior bond-holders (though voluntary burden sharing with subordinated bondholders did take place through the Liability Management Exercise (LME), as outlined later in this chapter).

The Joint Committee wanted to know why the burden was not shared with the senior bondholders.

As with our investigation of matters pertaining to Ireland’s entry to the Troika Programme in Chapter 10, the work of the Joint Committee work was limited due to the fact that the ECB did not appear before the Committee, despite being invited to attend. Furthermore, other foreign stakeholders were not invited to appear (for example representatives of the G7 countries2 ).

Kevin Cardiff made the following observation in his witness statement to the Joint Committee:

“There had been a small experiment in senior bond burden-sharing earlier in the crisis period. Irish Nationwide offered at one stage to buy back senior bonds from the market at the reduced price at which they were then trading. The amounts were small and no bondholder was going to be forced to take the deal, but the reaction from Moodys credit rating agency was very swift. They came very close to downgrading the whole Irish banking system, on the basis that any wavering in the Government’s support to the banking system and its creditors, even on such a voluntary basis, would be tantamount to a declaration that all bondholders could expect to make losses. That the initiative was the building society’s not the Government’s made no difference. This position was somewhat surprising, but indicated the extent to which any burden-sharing with senior bondholders might be expected to ‘shock’ the market.”3

Patrick Honohan, Governor of the Central Bank, in his written statement to the Joint Committee, explored some of the possible options open to Government immediately prior to the expiration of the Guarantee in 2010: “...faced with the steep cliff of bank liability maturities in September, I gave some consideration to possible alternative courses of action which might be recommended to Government.”4

In a footnote to his statement, Patrick Honohan, Governor of the Central Bank suggested that:

“…one possibility was for the Government to abrogate the bank guarantee (in respect of Anglo and INBS) in August or September 2010 and to bail-in the bond holders and potentially large depositors. While, if successful, such a measure would have reduced the amount paid out to bank creditors by the State, it would also have represented a very large and conspicuous default of the State on a class of creditors which it had created by virtue of the guarantee and confirmed by the CIFS legislation of October 2008.”5

Notwithstanding the possibility of imposing losses on senior bondholders, it was stated that the view of the ECB was also central to the success of any decision, if one had been taken. Patrick Honohan observed:

“It seemed doubtful whether it could even be successfully accomplished: for example, pressure from the ECB might well have resulted in any such decision having to be reversed in a way that resulted in the State resuming its obligations in regard to these liabilities while still suffering the loss of market credibility implied by a default.”6

An earlier NTMA position on the matter, presented in evidence by Brendan McDonagh, Director of Finance, NTMA, is worth noting. In his evidence to the Joint Committee he said:

“Up until … May 2009 when I was with the NTMA, there was a very strong view that... senior bondholders definitely needed to be repaid their money and there was no talk of a bail-in at that stage.”7

The total bonds in issue as at 1 April 2011 were €64.3 billion, split as per the table below:

| €m | Senlor Bonds Guaranteed | Senior Bonds Unguaranteed Secured | Senior Bonds Unguaranteed Unsecured | Subordinated Bonds |

|

AIB |

6,063 |

2,765 |

5,872 |

2,601 |

|

BOI |

6,178 |

12,284 |

5,164 |

2,751 |

|

EBS |

1,025 |

1,991 |

472 |

65 |

|

IL&P |

4,704 |

2,999 |

1,156 |

1,203 |

|

Anglo |

2,963 |

0 |

3,147 |

145 |

|

INBS |

0 |

0 |

601 |

175 |

|

Total |

20,934 |

20.039 |

16,413 |

6,940 |

|

Above table extracted from the CBI official site - Press Release: Updated Information Release 1 April 2011 |

||||

Source: Department of Finance submission to the Banking Inquiry8

The expiration of the State Guarantee at end of September 2010 may have presented a new opportunity to share the burden of the various recapitalisations of the Covered Institutions with holders of bonds coming out of the Guarantee. One such possibility was said to have been discussed between Alan Ahearne, Special Advisor to Brian Lenihan, the former Minister for Finance and IMF officials in early October 2010, when the Minister was attending an IMF meeting in Washington DC. This discussion took place not long before a large payment was required to redeem the Anglo bonds.9 Evidence was given by Alan Ahearne concerning this meeting as follows:

“I went to Washington DC with him [the Minister], because you mention the IMF, in early October and I met with a couple of IMF officials, I think one of whom you’re meeting tomorrow. [The Joint Committee were to meet Ajai Chopra next day.] And … they said “Is the Minister aware that there’s about €4 billion of Anglo bonds that are now unguaranteed, senior non-guaranteed?” I said he is aware of that and he was aware of that. They said “It’s a lot of money”, and I said “He’s aware of that.” So it was clear from the short discussion I had with them at that stage that they had spotted this and they had these concerns.”10

Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director of the IMF, commented that he “would not distinguish” between the ECB and the European Commission in terms of seniority, as they were both “working in concert.”11 Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, also commented that “Clearly, there was a bit of give and take in all this…but the IMF was an equal partner as the other institutions.”12

The IMF maintained a positive disposition towards burden-sharing as discussions on a possible bailout programme got underway. The “IMF approach” included burning holders of unguaranteed, unsecured senior bonds. As described by Aja Chopra in his evidence to the Joint Committee, IMF staff were:

“…of the view that imposing losses on just junior bondholders was not sufficient and that the issue of imposing losses on senior, unguaranteed, unsecured bondholders should also be explored and I listed criteria for this, which is: look at the overall magnitude of banks’ losses, to look at the issue of returning the banks to a more stable funding structure and also to look at the issue of potential knock-on effects on others. And as I said in the statement, this needs to be done within a robust legal and institutional framework that strikes a reasonable balance between creditor safeguards and flexibility.”13

In his evidence to the Joint Committee, Kevin Cardiff noted his understanding of the Troika parties’ initial position on burning bondholders:

“As the bailout discussions got underway formally after 21 November 2010, we thought the IMF might be open to the idea of having some of the senior bank bondholders take losses on their investments in the banks. We were pretty sure the ECB would be dead set against and the Commission too was likely to be against the idea, but maybe not so strongly.”14

Evidence presented to the Joint Committee would suggest that the IMF and European institutions may indeed have been working with different considerations in mind. For instance, Ajai Chopra noted that: “…the key issue became the issue of contagion… they [the European institutions] were very concerned that moving on imposing losses on senior bondholders in Ireland would adversely affect euro area banks and their funding markets.”15

Asked if the dominant consideration of the European Commission and the ECB was the spill-over effect to the wider Eurozone of imposing losses on holders of bonds in Irish-owned banks, Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs with the European Commission confirmed:

“...you are correct in this. So the spillovers … were … in particular to the rest of the euro area. However … the EFSF and the EFSM going out and borrowing to on-lend to Ireland in a situation on even potentially larger market unrest and even higher interest rates would have been … damaging for Ireland also. So the effects ... the negative loop from Ireland to the rest of the euro area and back to Ireland … were certainly present in the assessment.”16

Ajai Chopra said:

“The view of the IMF staff was, this does need to be taken into account but that this was something that was anticipated by markets and if it was done within the context of a programme where the sovereign has already lost access to markets, it is something that the markets should have been able to absorb and even if they were not able to absorb it, there were mechanisms to help address that contagion…”17

He also said:

“Recent academic research confirms the view that spillover risks were exaggerated. An empirical analysis of funding cost spillovers in the euro zone (NBER Working Paper 21462, August 2015) finds that contagion between most euro zone banks is limited because they have fairly weak links, and that contagion risks are significant only when the biggest euro zone banks are involved.”18

The IMF was in favour of reaching a positive decision on having some of the senior bondholders take imposed losses on their investments.

Ajai Chopra said that, in November 2010, “IMF staff made Lee Buchheit, a specialist international lawyer on these matters, available to the Irish authorities in Dublin to advise on how burden sharing might be done to avoid legal challenges.”19 This evidence was supported by Pádraig Ó Ríordáin of Arthur Cox, Legal Advisor to the Department of Finance.20

According to Kevin Cardiff:

“At the time, we were led to believe that Dominique Strauss-Kahn, head of the IMF, was not only in favour of this approach but believed he could persuade other major players in world finance, including the major European Governments, the Americans and the ECB to go along. Strauss-Kahn was to, and did, convene a conference call to pursue this arrangement. There had even been early indications of a positive hearing from US Treasury Secretary Geithner.”21

We heard that the viewpoint of then US Treasury Secretary, Timothy Geithner was allegedly crucial in Ireland’s attempts to impose losses on senior bondholders. As Cathy Herbert, Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, told us:

“It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that putting Ireland into a bailout programme was killing a number of birds with one stone. It solved the ECB’s problem with the extent of our banks’ dependence on the Eurosystem for emergency lending and it eased the concerns of the then US Treasury Secretary, Tim Geithner who made clear to his European colleagues at the G-7 meeting in Seoul earlier in November the need to prevent a banking collapse in Ireland in order to protect the global financial system.”22

In his evidence, Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, said: “Tim Geithner was Secretary to the Treasury in the United States, and I met Tim Geithner on several occasions, and he’s often recited as being somebody who was against burden-sharing, and he was, he makes no bones about it.”23

We also heard of the alleged intervention by external political actors in the final stages of the negotiations on a Troika Programme. According to Alan Ahearne: “I understood it was a G7 conference call, but it may not have been, but it obviously involved sort of people at that level, and that it had been decided that the burning of bondholders had been vetoed.”24

Patrick Honohan told us that he had asked Brian Lenihan if he had considered doing something about it. He said that the Minister replied: “I can’t go against the whole of the G7.” He [the Minister] thought it was “politically, internationally politically inconceivable…”25

The Troika agreed to refinance Ireland in November 2010, with the first major drawdown from the Troika Programme made in January 2011. Imposing losses on senior bondholders without imposing losses on depositors, while at the same time entering a Troika Programme, was apparently not an option at this point. Patrick Honohan said: “…No, the decision has been taken. There is not going to be a programme if you burn the bondholders.”26

Commenting on the view that bondholders were ranked equally with depositors and the issues that may arise in burden-sharing, Patrick Honohan said:

“This is all under Irish law … an argument not fully recognised by a lot of the outside observers who said, “Why are you paying for the banks? ... They didn’t realise that the obligation to the creditors of the banks had become equal in importance to the … status of debt holders.”27

The former Attorney General, Paul Gallagher, when asked in relation to the legal difficulties of burning bondholders said “…it would be foolish and misleading to suggest that that wouldn’t give rise to legal difficulties; it would. We considered those very carefully and, indeed, post the bailout, I had various meetings to look at that.”28

Paul Gallagher then went on to talk about those meetings. He told the Joint Committee:

“I had meetings also with IMF representatives and specialist lawyers to consider that and we confirmed repeatedly that that could be done in legal terms, notwithstanding the legal difficulties, and it depended solely of the approval of the Troika to doing that, and that as you know was prohibited and was a condition of the bailout.”29

Marco Buti offered the following assessment:

“At the end of the day, the Troika are three partners and we came to the common judgment that this was not the right thing to do. The ECB was very forceful on that. I think with hindsight ... I think it was the right thing to do - not to go for the bail-in of senior bondholders.”30

Evidence received from the NTMA is also worth noting. John Corrigan, Chief Executive Officer NTMA, wrote to Brian Lenihan on 28 November 2010, stating that he had:

“… learnt during the course of the discussions that the external authorities and the European Central Bank (at board or equivalent level) had taken the view that burden sharing with unguaranteed bank senior bond holders was “not on the table.” It is unfortunate that, notwithstanding the fast moving pace of recent events, I was not made aware of this outcome.”31

The Government agreed to enter the Programme with the Troika on 28 November 2010 (as explored in Chapter 10). Burden sharing with bondholders was not a part of this agreement. However, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Ireland and the Troika partners made no mention of senior bondholders.32 The Joint Committee wanted to know: was there an understanding or a belief that burden-sharing could take place at a future date?

Patrick Honohan, referring to the holders of bonds in the banks which were not going concerns, said:

“…we never committed to not burning the bondholders. We committed to not including the burning of bondholders in the programme … So, it was still there for attitudes to shift…”33

A new Government was elected on 9 March 2011 and began exploring the possibility of burden-sharing. This was done in tandem with the Financial Measures Programme (explored in Chapter 8), which created the Pillar Banks and provided for the merger and wind down of Anglo and INBS.34

Ajai Chopra said:

“When the new government took office in March 2011, about three months after the launch of the program…Their position was that the pillar banks need to be able to operate in the market as strong banks with a positive future and ongoing relations with all counterparties. In making such a distinction, the hope was that burden sharing with the senior creditors of the failed banks would be allowed.”35

From the Joint Committee oral hearings, it would appear there was still a belief on the part of the Government that burden-sharing would be possible once the Troika Programme had begun and the restructuring of the banking system, as outlined in the Financial Measures Programme (FMP), had taken place. As Patrick Honohan explained:

“I wrote to the Minister, the new Minister, Michael Noonan, offering my advice on this matter, and I said, ‘Look, the ECB are firmly against, for going-concern banks, but it is possible that they would accept a bail-in for the ... for Anglo and INBS.’”36

The restructuring of Anglo and INBS element of the FMP was submitted by the outgoing Government in January 2011.37

Michael Noonan, who was elected to office in March 2011 said:

“Building upon the advice of the Department of Finance, the NTMA and the Central Bank, I announced the Government’s pillar banking strategy. The strategy set out the Government’s plans in relation to what I would describe as the going-concern banks, that is, Bank of Ireland, AIB, EBS and Irish Life and Permanent. It was the Government’s response to the announcement by the Central Bank of Ireland of the results of their PCAR or stress tests. The objective was to have smaller, domestically focused and well-capitalised banks operating in Ireland. A joint restructuring plan for the other banks, Anglo Irish Bank and Irish Nationwide, had been submitted to the European Commission by the previous Government in January 2011 and these institutions had no role in the strategy at that time.”38

In his written statement to the Joint Committee, Ajai Chopra gave his interpretation of the Pillar Bank strategy:

“The purpose was to leave open the possibility for burden sharing with senior bondholders later in the program, especially for failed banks where there was a stronger case for greater burden sharing with creditors. In particular, Anglo Irish was a failed bank with losses that were many multiples of its capital and it did not need to worry about future counterparty relations. Sizeable liability management exercises for banks’ junior debt were underway when the program started and further such exercises were envisaged, helping to reduce fresh injections of capital by the government.”39

Within the NTMA in early 2011, the possibility was also explored, as John Corrigan said:

“...the NTMA commissioned a study to look at a bail-in burden-sharing scheme involving senior as well as subordinated debt holders in the covered institutions…”40

The scheme identified substantial potential savings, depending on the level of discount or haircut applied and the institutions involved. The NTMA recommended that burden-sharing with senior bondholders be initiated following PCAR/PLAR results in March 2011.41

Irish senior unsecured bank bonds were trading at levels consistent with clear anticipation of a cut in the principal, reflecting that some burden-sharing was anticipated.42

Liability management exercises with subordinated bondholders were pursued through 2011, which helped mitigate the cost to the State of the Central Bank’s 2011 PCAR (discussed further in Chapter 8), the results of which were announced on 31 March 2011 and which identified an additional capital requirement of €24 billion.

A second attempt at burden-sharing with senior bondholders was not successful, even though there was an expectation that it could be.

We wanted to know what prevented this from happening. Given the significance of this episode, it is worth quoting evidence heard by the Joint Committee in this regard.

Kevin Cardiff said:

“Finally, however, we got the message (I heard it by telephone from an ECB official, but Ministers may have heard directly also, I understand, and the same message was passed also by email) that in fact the ECB Governing Council had decided to make it clear to us that in the event that we pursued even the merest modicum of burden-sharing – even purely voluntary – we could not expect any supporting statement from them, thus undermining all the power of the banking announcements.”43

He added:

“…we had been negotiating for months with them for ... to get some sort of really positive statement that would say the ECB is behind us … And the instruction from the ECB was that, if you want that prize, you do not burn anybody, any way senior, senior bonds, at all. And it was quite explicit.”44

Kevin Cardiff told us that the “decision” of the ECB was “very close to being an instruction. ”45

As part of the announcement of the FMP, announced on 31 March 2011, the Irish Government wanted a positive statement from the ECB to demonstrate that the ECB was behind Ireland and its restructuring of its banking system.46 According to Kevin Cardiff, the ECB made explicitly clear that if Ireland wanted such a positive statement from the ECB, it could not burn any senior bondholders in any way.47 The positive statement requested by the Irish Government was issued by the ECB on 31 March 2011.48

Minister for Finance, Michael Noonan said:

“The issue of burden sharing with IBRC [Anglo and INBS] was considered. There was €3.7 billion of unsecured unguaranteed senior debt in Anglo and INBS in early 2011. As IBRC was different from the other banks, the Government pushed for burden sharing for these bondholders, conditional on the support of the ECB. In advance of my statement on banking matters on 31 March 2011, I had sought ECB support and the initial speech that I made to the Dáil ... the draft of the initial speech that I made to the Dáil included a statement on burden sharing for this €3.7 billion. However, despite our best efforts, it was made clear to both the Taoiseach and myself and my officials that the ECB would not support such a statement or moves to burden share with IBRC. Weighing up the potential savings of €3.7 billion that would accrue to IBRC against the immediate and devastating impact of withdrawal of ECB support on Ireland, the Government took the decision not to proceed with the burden sharing with senior bondholders.”49

Attending at the Institute of International and European Affairs meeting at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, the former ECB President, Jean-Claude Trichet, was asked by the Joint Committee whether the ECB had threatened the withdrawal of support, in particular using the metaphor of a “bomb” going off in Dublin, if burden-sharing was pursued. In response, Jean-Claude Trichet said:

“What I certainly said, because we had discussed that in the governing council of the ECB, was that it was unwise to do that. And that was our strong feeling at the time where Ireland was helped by us more than any other country in ... as I already said, in Europe, and perhaps in the world. So let’s put yourself in the situation. We have a country which is progressively regaining competitiveness in very, very difficult times. We expressed only the sentiment of the Governing Council to the Government or Ireland. The Government of Ireland is responsible and the Government of Ireland takes decisions.”50

There were two phone calls between the ECB and Minister Michael Noonan, on 31 March 2011, as indicated previously by Michael Noonan. In his evidence to the Joint Committee, the Minister conveyed to us the substance of these phone calls:

“So what it came down to was how we would arrange things and what the amount would be and then I told him that as part of the programme, we were burning bondholders and he didn’t agree. He didn’t agree and he asked me was I aware that this would be treated by the markets as a default, which was reasonably strong pressure because I know that after the time you’ve put in here, you understand the details of all this thing. ELA, emergency liquidity assistance, was underpinning Anglo to the tune of €41 billion at that time. ELA can’t be given to a bank that defaults.”51

Michael Noonan said that Jean-Claude Trichet:

“…raised the question of the financial services industry in Ireland and particularly in Dublin and he suggested that even though he couldn’t say categorically, it might not be possible for people in the financial services in Ireland, particularly in Dublin, to finance themselves on the market if they were situated in a country that was in default.”52

Michael Noonan consulted with officials and, on a subsequent telephone call with Jean-Claude Trichet, reaffirmed the Government’s position. In response, he said that Jean-Claude Trichet:

“…sounded irate but maybe he wasn’t irate but that’s the way he sounded and he said if you do that, a bomb will go off and it won’t be here, it’ll be in Dublin.”53

The Joint Committee asked Michael Noonan about the level of engagement that he had with Jean-Claude Trichet on the specific issue of burning unguaranteed bondholders. The Committee asked: “you talked about the two phone calls that you’ve had with Mr. Trichet during… that day... What other engagements did you have with Mr. Trichet in relation to the burning of bondholders, before or after?” to which Michael Noonan replied, “I didn’t revisit it after that. ”54

When in Kilmainham, Jean-Claude Trichet gave his general view of the ECB’s relationship with the Irish Government:

“You know exactly what were our relationship. We have published our letters. Full stop. You have to know ... you know with the adjective, the comma, the full stop, exactly what was our relationship with Ireland. You have the letters ... the four letters that have been published. The rest of it I can only ... I assume totally the fact that the Governing Council of the ECB considered it was not appropriate for Ireland in the situation in which Ireland was, which was one of the worst you could imagine, to go along this burning and that you would have had probably a lot of very adverse consequences. It was finally what was decided by the Government, if I’m not misled. The decision was not taken by the ECB. ”55

As in November 2010, the March 2011 attempt by the new Government to impose losses on senior bondholders, this time likely focussing on the now defunct institutions, such as Anglo and INBS, was not successful. Once again, the intervention of the ECB appears to have been critical. The voluntary liability management exercises with subordinated bonds continued, and this is addressed further detail below.

The Joint Committee referred Michael Noonan to comments that he made on RTÉ from Washington DC on 15 June 2011 that seemed to indicate that the Government would again pursue the burning of bondholders in Anglo Irish Bank and INBS, with the consent of the ECB. In response, he said:

“Because I was … now had moved my negotiation on to changing the promissory note and, as part of the promissory note, the bondholder issue was still in there. I hadn’t conceded … I never agreed with Trichet. I never agreed with Trichet. I never told Trichet we wouldn’t go ahead. What we did was I made a statement in the Dáil and that was that we weren’t including it in what was announced to the Dáil that day, and then the promissory note discussions were very intricate and took a long time to get a result.”56

Michael Noonan further clarified:

“The conversations I had with the Commission and with the ECB and with the IMF after that was that we could not continue paying €3.1 billion every March to service a promissory note arrangement … and that we needed it restructured, and that as part of the restructuring the issue of senior bondholders would have to be revisited.”57

Ajai Chopra said:

“The EC and ECB often put euro area-wide concerns above what is appropriate for the individual member. The obvious example is the issue of burden sharing with senior unsecured bondholders, where European institutions focused on wider euro area concerns even if this resulted in a higher burden for Irish taxpayers and higher Irish public debt…”58 and “…it is understandable that there is a strong sense in Ireland that burden sharing between Irish taxpayers and bank creditors has been unfair.”59

Irish taxpayers were inappropriately burdened with banking debts arising specifically from a failure to impose losses on senior bondholders in any of the Covered Institutions.

Separate to the evidence outlined above, the Joint Committee were interested in the following questions:

These two questions are considered below.

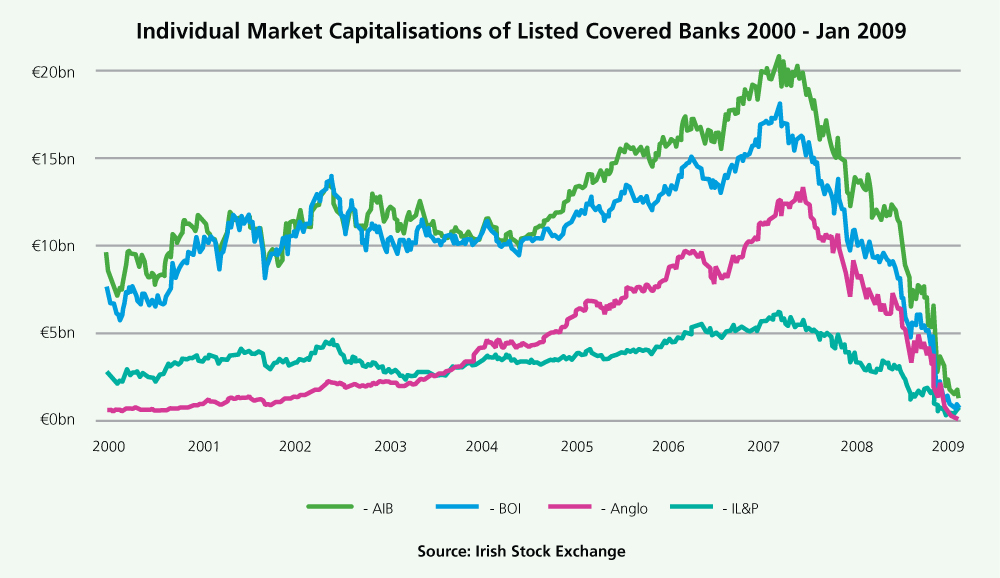

As illustrated in the graph below, the value of shareholder investments reduced by 100% in the case of Anglo and circa 99% in the case of AIB, Bank of Ireland and IL&P over the course of 2008. The combined market capitalisation of the four banks reached a peak during 2007 of circa €53.7 billion60 before tumbling to a low of €141.6 million, as the effects of the financial crisis took hold.

Source: Nyberg61

Throughout the period 2009 to 2011, Irish banks carried out a number of Liability Management Exercises (LME). This was essentially the equivalent of burden-sharing with junior bondholders on a voluntary basis. Under LME, the banks bought back or replaced a number of the existing subordinated bonds totalling €24.6 billion of debt for a price of €9.5 billion. In that way, the banks reduced their liability by €15.457 billion (€10.259 billion pre-March 2011 and €5.198 billion post-March 2011), reducing the level of recapitalisation required from the taxpayer.62

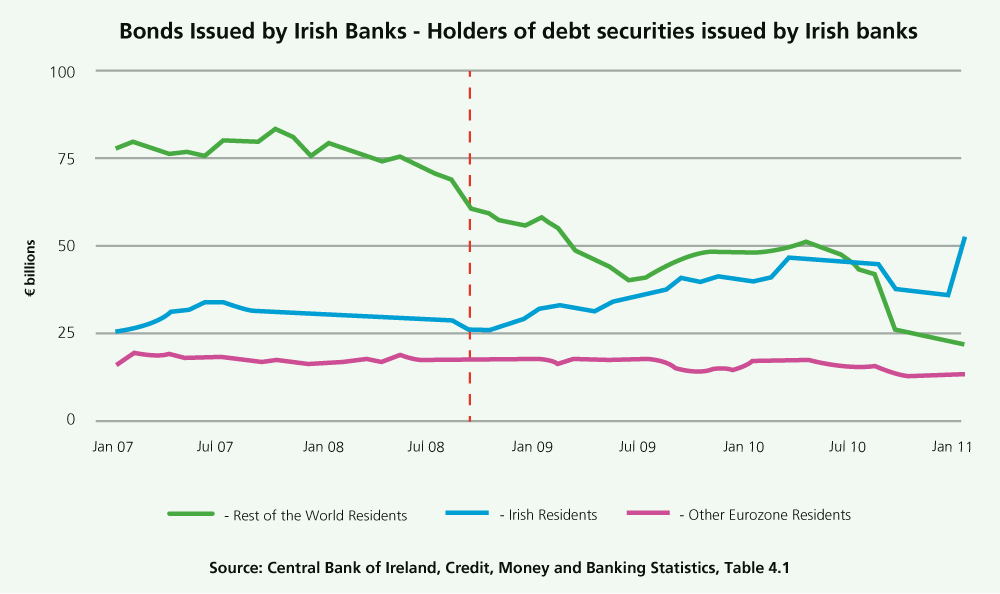

A proportion of Irish bank bonds were owned by foreign investors throughout the period under review, albeit that trend underwent a downward trajectory from early 2008 onwards. With bond prices dropping significantly over this period, these subordinated bondholders would likely have been burned as part of the LME, if they volunteered to do so.

Legislation passed on 7 February 2013 triggered events of default under a range of agreements between IBRC, the Central Bank of Ireland and third parties.63

As illustrated in the following graph, foreign holders of Irish bank bonds had greatly reduced their holdings between 2008 and 2010 to the extent that less than 50% of these bonds were held outside of Ireland by the end of 2010.

Source: Seamus Coffey64

If the aim of burning bondholders was to reduce the liabilities of the banks (and thus the taxpayer) while also reducing potential losses to Irish investors, the graph would suggest that the most effective time to burn bondholders may have been during the period immediately before the Government Guarantee was put in place.

However, it would appear that there was an intention, or expectation at least, on the part of the IMF that burden-sharing could be imposed on bondholders once the State Guarantee had ended (as noted earlier).

In our oral hearings, the Joint Committee explored what might have been saved in burning bondholders and when may have been the most advantageous time to do this.

As stated above, 2008 would have been the most advantageous time to burn bondholders in terms of what might have been saved. However, the following evidence is from individuals who only discussed the scenario from late 2010 onwards.

As of November 2010, outstanding unsecured, unguaranteed senior bonds were said to amount to approximately €16 billion. Ajai Chopra, using a ‘rule of thumb’ , said that €8 billion may have been saved had a haircut been applied to these bonds.65 Kevin Cardiff said that the IMF put the senior estimated unsecured debt figure to be between €18 billion and €19 billon.66

Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General in the Department of Finance was of the view that, had burden-sharing happened in late 2010 in relation to Anglo or INBS, that €3.6 billion would have been on the table.67 Alan Ahearne gave a similar estimate, when he said the amount of money available from Anglo bonds for burden sharing in November 2010 was “€3.5 billion or €4 billion.” On the question of potential savings, Alan Ahearne said that Brian Lenihan “had in his mind 50% discount so you might say €1.5 billion to €2 billion [would have been saved from applying haircuts to Anglo bonds].”68

Documentation seen by the Joint Committee and prepared by the Department of Finance estimated that, as of 1 April 2011, the Covered Institutions had issued bonds valued at €64.3 billion, which were split between guaranteed and unguaranteed secured and unsecured senior bonds (€57.4 billion) and subordinated bonds (€6.9 billion).69

At the end of March 2011, the NTMA produced a ‘Bail-In Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt’ .70 This strategy document estimated that of the €12.7 billion senior unsecured debt and the €6.5 billion subordinated debt in AIB, Bank of Ireland, EBS and IL&P, a haircut amount of approximately €12.5 billion could be achieved.71

AIB and Bank of Ireland outlined their concerns on burden-sharing.72 They were of the view that burden-sharing with senior debt should only apply to non-viable institutions. The primary implications in the view of AIB and Bank of Ireland were:

The NTMA were of the view that these adverse effects could be ameliorated if burden-sharing with senior debt was conducted system-wide with the benefit of existing legislation.73

However, it is not clear from evidence before the Joint Committee whether unsecured senior debt in the going concern banks as at 31 March 2011 was being actively considered for burden-sharing by the Government.

| Debt Eligible for Restructuring | Haircut Levels | Haircut Amounts | |||||

|

Bank |

Senior Unsecured € m |

Junior € m |

% Senior |

% Junior |

Amount Senior € m |

Amount Junior € m |

Total Amount € m |

|

AIB |

5,864 |

2,600 |

60% |

90% |

3,518 |

2,340 |

5,858 |

|

BOI |

5,198 |

2,581 |

45% |

80% |

2,339 |

2,065 |

4,404 |

|

EBS |

520 |

150 |

60% |

90% |

312 |

135 |

447 |

|

IL&P |

1,156 |

1,203 |

60% |

90% |

694 |

1,083 |

1,777 |

|

Total |

12,738 |

6,534 |

6,863 |

5,623 |

12,486 |

||

|

Source: AIB/BOI/EBS/IL&P, Lazard Frères and Central bank of Ireland |

|||||||

Source: NTMA74

In relation to Anglo and INBS, there were “€3.6 billion of senior unsecured unguaranteed bonds and €0.1 billion of subordinated liabilities” that could be subject to haircuts.74 Of this, the NTMA was of the view that potential savings to the State of €2.4 billion could be achieved.75

| Debt Eligible for Restructuring | Haircut Levels | Haircut Amounts | |||||

|

Bank |

Senior Unsecured € m |

Junior € m |

% Senior |

% Junior |

Amount Senior € m |

Amount Junior € m |

Total Amount € m |

|

Merged Anglo/INBS |

3,629 |

141 |

63% |

90% |

2,286 |

127 |

2,413 |

|

Source: Anglo/INBS and Lazard Frères |

|||||||

Source: NTMA75

Taken together, the NTMA estimated that €9.1 billion might have been saved if haircuts – which ranged from 45% in Bank of Ireland up to 63% in Anglo/INBS - had been applied to senior, unsecured, unguaranteed bondholders across the six Participating Institutions at the end of March 2011.76 This would have comprised of €6.863 billion from the four main banks and €2.286 billion from Anglo/INBS.

The recommendation made by the NTMA was:

“Given the … fact that the markets are expecting and have priced in burden sharing with subordinate and senior debt, it is the recommendation of the NTMA that, subject to a view being taken by Government on the potential implications of an adverse reaction from the external authorities and the implementation of an appropriate legal framework, immediate steps should be taken following the announcement of the PCAR/PLAR results to enable burden sharing with both senior and subordinated debt.”77

However, we are ultimately of the view and must stress that it is not possible to estimate the exact savings that could have been achieved from burden-sharing by the Government, if the decision to do so was taken, as savings would have been dependent on the haircut applied, the type of bond being “burned” , the timing of the move and the particular institutions included.78

Chapter 11 Footnotes

1. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-192.

2. The G7 countries are Canada, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, Japan and United States.

3. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-193. See also Moody statement, 6 August 2009. Source: https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-reviews-Irish-Nationwide-ratings--PR_184442

4. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, statement, PHO00009-003/004.

5. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, statement, PHO00009-003.

6. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, statement, PHO00009-004.

7. Brendan McDonagh, former Chief Executive Officer, NAMA & Director of Finance, Technology & Risk NTMA, transcript, INQ00090-024.

8. Department of Finance submission to the Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015, DOF07852-010.

9. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-006.

10. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-006.

11. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, International Monetary Fund, transcript, INQ00101-033.

12. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-035.

13. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, International Monetary Fund, transcript, INQ00101-009.

14. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-192.

15. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, International Monetary Fund, transcript, INQ00101-009.

16. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-015.

17. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-008.

18. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, statement, ACH00001-011.

19. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, statement, ACH00001-010.

20. Pádraig Ó Ríordáin, Partner, Arthur Cox, transcript, INQ00111-012.

21. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement KCA00002-031.

22. Cathy Herbert, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, statement, CHE00001-010.

23. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-015.

24. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-007.

25. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-086.

26. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-070.

27. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-011.

28. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, transcript, INQ00110-009.

29. Paul Gallagher, former Attorney General, transcript, INQ00110-009.

30. Marco Buti, Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, transcript, INQ00100-014.

31. Letter from John Corrigan, NTMA to Minister Lenihan re Burden Sharing, 28 November 2010, NTMA00024-001.

32. Memorandum of Understanding between Ireland and the Troika, 16 December 2010, DOF03460.

33. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-086.

34. Sale of Anglo & INBS Deposit Books, note for Minister 28 January 2011, DOF00807-006.

35. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, statement, ACH00001-010.

36. Patrick Honohan, Governor, Central Bank, transcript, PUB00352-086.

37. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-003.

38. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-004.

39. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, statement, ACH00001-010.

40. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-006.

41. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427-006.

42. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, statement, ACH00001-011.

43. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, statement, KCA00002-244.

44. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-045.

45. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00350-008.

46. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-082.

47. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-082.

48. “The Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) welcomes the Irish authorities’ rigorous assessment of the capital needs of Irish banks and supports the government’s commitment to ensure that these capital needs are met in a timely manner…” Extract from ECB press release 31 March 2011, AIB01838-003/4.

49. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-006.

50. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President of the ECB, at his appearance at the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham, 30 April 2015, transcript, INQ00140-032.

51. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-013.

52. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-013.

53. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-013.

54. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-027/028.

55. Jean-Claude Trichet, former President of the ECB, at his appearance at the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham, 30 April 2015, transcript, INQ00140-032/033.

56. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-028.

57. Michael Noonan, Minister for Finance, transcript, INQ00102-028.

58. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-005.

59. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, statement, ACH00001-010.

60. Department of Finance submission to the Banking Inquiry, 15 April 2015, DOF07852-013.

61. Nyberg Report, Misjudging Risk - Causes of the Systemic Banking Crisis in Ireland, Figure 2.3, PUB00156-019.

62. Department of Finance submission to the Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015, DOF07852-012.

63. Dept. of Finance, IBRC in Special Liquidation. Background Information and Current Status Update. 6 Nov 2013, DOF05679-001.

64. Seamus Coffey, Lecturer in Economics, University College Cork: Source: http://economic-incentives.blogspot.ie/search/label/Central-Bank- Statistics Raw Data taken from: http://www.centralbank.ie/polstats/stats/cmab/Pages/Money-and-Banking.aspx , Table 4.3.

65. Ajai Chopra, former Deputy Director, IMF, transcript, INQ00101-017.

66. Kevin Cardiff, former Secretary General and Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, PUB00351-011.

67. Ann Nolan, Second Secretary General, Department of Finance, transcript, INQ00076-019.

68. Alan Ahearne, former Special Advisor to the former Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, transcript, INQ00094-007.

69. Department of Finance submission to the Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015, DOF07852-010.

70. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427.

71. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427-004.

72. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427-005.

73. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427-005.

74. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427-004.

75. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427-005.

76. John Corrigan, former CEO, NTMA, transcript, INQ00106-016.

77. NTMA, Bail-in Strategy with Holders of Senior and Subordinated Debt, NTMA00427-006.

78. Department of Finance submission to the Banking Inquiry, 13 April 2015, DOF07852-010.